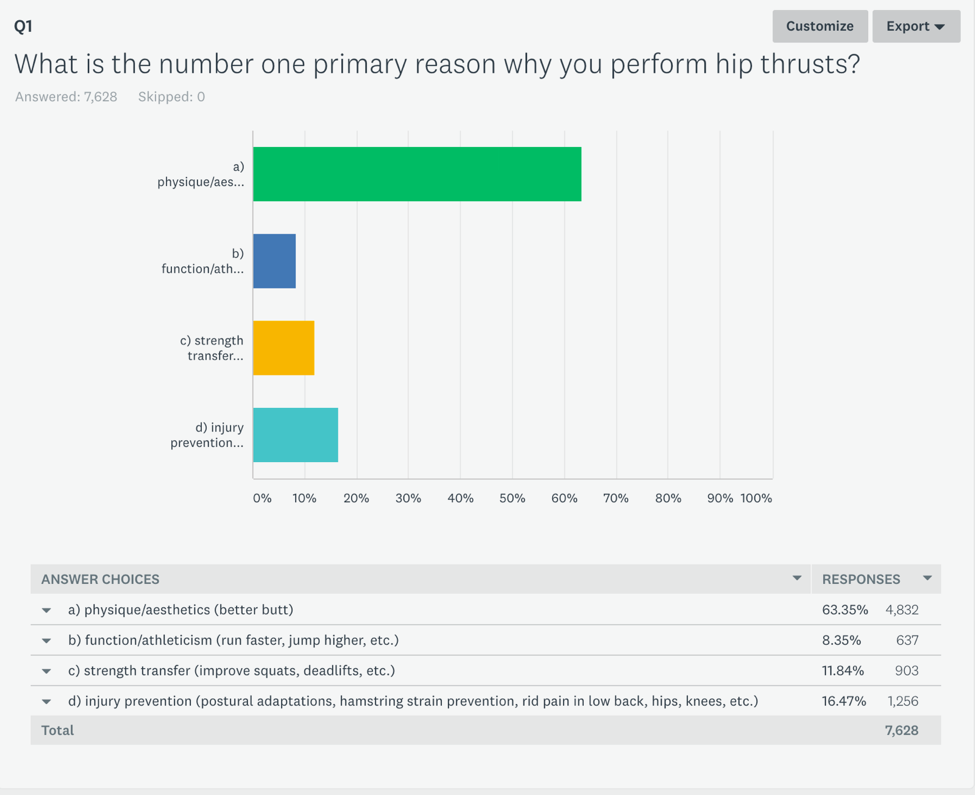

The hip thrust has gained a lot of momentum in the past decade, and people employ the hip thrust in their training for a variety of reasons. I recently polled my newsletter list and social media followers and received over 7,600 responses as follows:

Reasons why people thrust

As you can see, around 63% of people hip thrust primarily to attain a better butt, 8% to improve running and jumping performance, 12% to boost squat and deadlift strength, and 16% to prevent injuries. This article is geared toward sports scientists, strength coaches, and the 8% of people who hip thrust for functional performance.

Hip Thrust Wiki Page

I’m going to reference various studies in this article. In case you’d like to find a certain paper, know that I keep THIS Hip Thrust Wiki page up to date. It includes all the latest studies, anecdotes, experiments, and theories pertaining to hip thrusts.

Science Prevails Over Time

Science is the systematic knowledge of the physical and natural world gained through observation and experimentation. In theory, it should be perfect. Because humans are inherently flawed, however, we inevitably muck up the flow of science. Nevertheless, given ample time, science is self-correcting and converges on the truth.

In this article, I am going to use the case of the hip thrust as a teaching tool relating to human biases and how they effect scientific progression.

How Did the Hip Thrust Hysteria All Begin?

Almost 11 years ago, I thought up the barbell hip thrust in my garage gym in Scottsdale, Arizona. Since then, I’ve been on a mission to popularize the movement. Click HERE to read about the evolution of the hip thrust.

When I began programming the hip thrust to my clients, they reported improvements in a variety of physical and functional outcomes, most notably: increased glute size, increased running speed, and improvements in low back pain. I have sought to provide evidence for these observations over the years. In fact, I even proposed the force-vector hypothesis, which states that the direction of the force relative to the human body plays a large role in determining the functional adaptations of that exercise. Click HERE to read the classic article on Force Vector Training.

I eventually got around to examining this exact topic for my PhD thesis. First, my team found that the EMG activity in the hip extensors (glutes and hammies – the “sprint muscles”) was markedly higher with hip thrusts compared to back squats. Click HERE to read the article on squat vs. hip thrust EMG activity.

Then, my team examined the force-time characteristics between squats and hip thrusts and found that the squat was superior in eccentric and total (but not concentric) measurements. Bear in mind that sprint acceleration is mostly concentric in nature. Click HERE to read the article on squat vs. hip thrust forcetime data.

Next, two strength coaches in New Zealand carried out the training study, and it was found that hip thrusts led to better acceleration improvements (and horizontal jump and isometric mid-thigh pull improvements, but not vertical jump improvements) than front squats in adolescent male athletes. Click HERE to read about the first RCT on hip thrusts vs. front squats on performance.

My team then found in a twin case study that hip thrusts led to better outcomes in glute hypertrophy and horizontal pushing force than back squats. Click HERE to read the classic twin case study on squats vs. hip thrusts.

Shortly thereafter, I was contacted by an American strength coach who had stumbled upon similar patterns of findings in a pilot study he’d run for his master’s thesis. Click HERE to read Michael’s master’s thesis on squats vs. hip thrusts vs. deadlifts.

Consider all of this information, I was on cloud nine! My theories were essentially validated – at least in my mind. With this much evidence pointing in the same direction, how could my predictions possibly be wrong?

Jumping the Gun

I took this information and ran with it, posting numerous article links and infographics on my social media channels relaying the news that hip thrusts are very well-suited for improving speed and that the force vector hypothesis was legitimate.

Hip Thrust Infographics

Unfortunately, I spoke too soon. The combination of 1) my inherent biases as an inventor, 2) my role as an online educator always seeking to provide cutting edge information to my followers, and 3) my greenness as a scientist prevented me from exhibiting a more tempered approach to the emerging evidence. Sure, I was very cautious in my conclusions and made sure to point out limitations in the peer-reviewed published articles. On social media, however, I was overenthusiastic and hasty; I shared, liked, favorited, re-tweeted, and reposted everything that confirmed my bias.

If I was a professor speaking to a classroom full of students about the hip thrust, I would have cautioned them by pointing out that 1) we have EMG, force plate, and ultrasound data but only one training study involving adolescent males, 2) we have a case study involving twin females that appear to be better-suited anatomically for hip thrusting than squatting, 3) we have a confident, charismatic, and undoubtedly biased inventor singing its praises, and 4) we need much more research examining the nature of transfer from hip thrusts to performance. As a prolific S&C educator with a large online following who gets rewarded for being “ahead of the research,” making bold predictions, and playing to the masses – in addition to being a biased inventor, might I add – I failed to be as scientific.

Fast forward two years: two studies have just been published, one of which I was a peer reviewer for and for which I recommended acceptance. Both of these studies had subjects solely perform the hip thrust while noting the changes in sprint speed – or better yet, the lack of change in sprint speed.

Click HERE to access study #1:

“Effects of Hip Thrust Training on the Strength and Power

Performance in Collegiate Baseball Players”

Click HERE to access study #2:

“Heavy Barbell Hip Thrusts Do Not Effect Sprint Performance:

An 8-Week Randomized-Controlled Study”

In the first study, 20 college male baseball players hip thrusted 3 times per week for 8 weeks in a progressive, periodized fashion and took their 3RM hip thrust strength from 295 lbs to 392 lbs (36% gain) and their 1RM parallel back squat strength from 185 lbs to 237 lbs (31% gain), with no improvements in vertical jump, broad jump, or 30m sprint speed.

In the second study, 21 university athletes (15 males and 6 females) hip thrusted 2 times per week for 8 weeks in a progressive manner using a 5 x 5 loading scheme and took their 1RM hip thrust strength from 356 lbs to 453 lbs (27% gain), with no improvements in 40m sprint speed.

Both utilized reasonable protocols that closely aligned with programs we commonly see in the field. Importantly, both studies showed very large increases in hip thrust strength.

Upon reviewing both of these papers, my initial reaction was to read the articles with skeptical eyes. I was highly convinced that hip thrusts are a great speed builder, after all.

It makes so much sense: to move forward faster, you have to produce high amounts of horizontal force, and this is largely carried out by the hip extensors. What better exercise is there than the hip thrust to accomplish this? Moreover, I’ve received, on average, an email a day for the past seven years from someone informing me that the hip thrust has enabled them to run faster than ever before.

With all of this in place, how and why did the subjects not gain speed, and how could I have been so wrong?

The great thing about science is that it is self-correcting over time. Critical findings are often never duplicated, and we’re frequently led on wild goose chases in the literature. But make no mistake about it: science eventually converges on the truth.

Anecdotes Aren’t All That

When I was training athletes 10 years ago and making these observations, we were not just performing the hip thrust. I had a fully equipped training studio, and in addition to plyometrics and sled pushes, we performed back squats, box squats, front squats, walking lunges, Bulgarian split squats, high step-ups, deadlifts, Romanian deadlifts, stiff-legged deadlifts, single-leg Romanian deadlifts, good mornings, kettlebell swings, horizontal back extensions, 45-degree hypers, reverse hypers, glute ham raises, and Nordic ham curls. Since we often performed hip thrust variations first in the workout, and I had a special machine designed for these (the Skorcher), the athletes that I trained typically attributed any speed improvements to the hip thrust. When I asked why they thought that way, they’d respond, “I can feel my glutes working on the ground similar to how they work during the hip thrust.” In actuality, it could have been any combination of the aforementioned exercises.

These statements were ultimately what led to the formation of the force-vector hypothesis, but they were subjective forms of evidence based on perceptions, and perceptions aren’t always valid. This line of reasoning is a logical fallacy known as post hoc ergo propter hoc, which is Latin for, “after this, therefore because of this.” It states that, “since event Y followed event X, event Y must have been caused by event X.”

Two more important points are worth mentioning. First, many of the clients reporting speed increases were runners and not sprinters. I felt that since the hamstrings and glutes become increasingly more important with increased running speed, then hip thrusts can only be more effective for faster running speed. Second, we never performed barbell hip thrusts off a bench. I never even thought of barbell hip thrusts until I wrote my glute e-book and was trying to figure out a way to teach hip thrusts to the masses, knowing full well that only a very small percentage of people would ever have access to a Skorcher (which I never ended up selling).

Skorcher Hip Thrust Variations circa 2007

There are, in fact, key differences between a barbell hip thrust performed off of a bench versus a Skorcher. In the case of the barbell hip thrust off a bench, the hips don’t sink as deep, the knee angle never opens up, and quadriceps activity is very high. The Skorcher barbell hip thrust causes the hips to dip down deep, which increases hip flexion and opens up the knee angle (knee extension) and stretches the hamstrings. This is essentially a stretch-shortening cycle for the hamstrings, and the hamstrings are likely the most important sprinting muscle.

My clients did barbell hip thrusts, band hip thrusts, barbell plus band hip thrusts, barbell plus chain hip thrusts, and single-leg hip thrusts off the Skorcher. They also performed their repetitions explosively and used lighter loads for higher reps compared to what I ended up employing in later years.

It’s still possible, then, that hip thrusts are great speed builders. However, the style of hip thrust should be similar to what was performed on the Skorcher. But again, the evidence that formed this hypothesis was based on logic (force vectors) and anecdotes from runners who were performing a wide variety of lower body exercises.

The Pendulum Swing

In fitness, pendulums are always swinging. The hip thrust saw a rapid rise in popularity over the past decade, and the two recent papers will likely cause the pendulum to swing the other way, especially with strength coaches. However, the two published papers had limitations, just like all papers do, in that they only utilized heavy loading protocols and only examined explosive functional parameters.

In time, the pendulum will likely continue to swing back and forth when papers are published supporting and not supporting the transfer of hip thrusts to various neuromuscular performance measures.

Current Opinions of a Biased Scientist

Now that I have pointed out my clear biases, what are my current thoughts on the hip thrust? When and how should they be used?

The vast majority of personal training clients train primarily for physique improvements. I firmly believe that hip thrusts are the best glute building exercise, more so than squats, deadlifts, or lunges. But right now, the only evidence I have is a ton of anecdotes (recall from earlier why anecdotes are a weak form of evidence) and a yet-to-be-published case study involving identical twins (many of you will remember the twin experiment where the hip thrust twin grew her glutes by 28% in terms of muscle thickness, and the squat twin by 21%).

Yes, we need better research. Some of this is underway; colleagues in Scotland are working toward obtaining this information. For those seeking greater glute development, the thrust is still a must, in my opinion.

But what about athletes? Are they worthless since they fail to improve sprint speed?

Here’s my take: right now, we have a paper involving adolescent male athletes showing superior improvements in acceleration, horizontal jump, and isometric mid-thigh pull strength, but not vertical jump with the hip thrust compared to the front squat; we have a pilot study on athletes showing promising potential; we have a controlled case study on twins showing superior glute gains and maximum horizontal force production compared to back squats; we have a study on college athletes showing no speed improvements despite large increases in hip thrust strength; and we have a study on baseball players showing large gains in hip thrust strength and surprisingly high transfer to the squat despite no improvements in speed or vertical and horizontal jump.

It may be that hip thrusts are more beneficial for younger athletes than more developed athletes. It may be that heavy hip thrusts are only good for developing maximal pushing force. It could be that dynamic effort hip thrusts and/or Skorcher-style hip thrusts, but not barbell hip thrusts off a bench, transfer well to sprinting.

We still need much research on the hip thrust examining other possible benefits to athletic performance, including agility/change of direction, throwing velocity, punching power, swinging power, and pushing force. However, the benefits of heavy barbell hip thrusts performed off of a bench on sprinting speed appear to not be as impressive as once thought. They may not improve sprint speed at all, in fact.

While we have several plyometric studies that support the force-vector hypothesis for resistance training, the hypothesis isn’t complete. You can’t just pick any old horizontal exercise and expect it to improve sprint acceleration or speed, nor can you perform any old vertical exercise and expect it to improve vertical jump. The exercise has to pass the real-world test, and the tempo, load, range of motion, and variation must be closely considered.

Despite what you commonly hear from powerlifters, the hip thrust is undeniably a great assistance lift for the squat – at least in the short-term. From the adolescent male athlete study, to the twin case study where I witnessed the hip thrust twin perform a not-so-pretty 95lb back squat in week one and a beautiful 135lb back squat in week six despite never performing a single repetition of a squat in between (not even in the warmup), to the pilot study, to the baseball player study, we are consistently seeing marked squat improvements from hip thrusting.

Interestingly, a recent meta-analysis showed that squats improve sprint speed. If A leads to B, and B leads to C, logical reasoning tells us that A should lead to C. In other words, if hip thrusts build the squat, and squats build sprinting speed, hip thrusts should also build sprinting speed, especially considering the fact that hip thrusts activate the hamstrings to a much greater degree than squats, and the hamstrings are the primary speed muscle.

As I’ve mentioned, this may have to do with the manner of execution of the hip thrust. Shoulder-elevated hip thrusts may be far inferior to shoulder- and feet-elevated hip thrusts (in which the hips sink low and the hamstrings are stretched) for improving speed, especially if coupled with explosive contractions.

As you can see, many thoughts are presently running through my mind. Based on the information I have presented thus far, I recommend that strength coaches and athletes continue to hip thrust, but when seeking speed improvements, opt for dynamic effort and Skorcher-style hip thrusts.

Where are we now?

- We need another study on adolescent males conducted by an independent lab to confirm the findings from my PhD thesis.

- We need a study examining glute hypertrophy between hip thrusts and other popular glute exercises such as squats and deadlifts. If it is found that hip thrusts effectively build the glutes, then we need to figure out why this increased glute mass is not translating to faster spring times. Could it be that some exercises build more functional glute mass than others? If so, this would refute what I’ve been saying over the past decade.

- We need comparative studies employing the same protocol between the hip thrust and the alternative exercise. When studies only measure the effect of a protocol involving one exercise, we’re unable to ascertain whether it’s the exercise or the loading protocol to blame for failing to improve performance.

- We need studies examining the effects of hip thrusts on maximal horizontal pushing force and sled pushing proficiency, as these are important qualities in sports such as football, rugby, and martial arts.

- We need studies examining the effects of hip thrusts on agility/change of direction, throwing velocity, punching power, and swinging power.

- We need a study examining free sprinting versus hip thrust plus free sprinting. It could be that hip thrusts are additive in nature when combined with sprinting, or the opposite (they could negate or neutralize the positive effects of sprinting).

- We need studies examining the effects of hip thrusts on pain, rehab, and injury prevention for the anterior hips, knees, lumbar spine, and hamstrings.

Sprinting speed is a very difficult ability to improve upon. Hell, check out THIS experiment which found that a program consisting of heavy parallel and quarter squats, mid-thigh pulls, and SLDLs failed to improve vertical and horizontal jump and 10 and 30m sprint performance. We perform many movements in strength and conditioning that, when performed alone in isolation, would fail to lead to meaningful improvements in speed. For example, chin-ups, rows, bench press, military press, dynamic and static core exercises, and certain lower body movements probably wouldn’t improve speed per se, but they would improve other elements of athletic performance and help bulletproof the body against injury.

As I’ve alluded to, I believe that hip thrust mechanics and loading protocols can be manipulated to transfer quite favorably to sprinting speed, but this is yet to be determined. It is quite possible that hip thrusts may rapidly improve a weak link in, let’s say, 3 out of 10 people, thereby enabling them to run faster and perform better, but when averaged out, no effect is seen. On the contrary, based on the same premise, hip thrusts may not be beneficial to some individuals and could actually make them slower due to fatigue-related adaptations.

It may be that I’m guilty of committing the No true Scotsman fallacy whereby I re-characterize the situation solely in order to escape refutation of the generalization:

Me: Hip thrusts improve sprint speed

Recent research: Hip thrusts don’t improve sprint speed

Me: Well, real hip thrusts (explosive Skorcher style) improve sprint speed

In the meantime, use the available evidence to form your own conclusion, and take into consideration anecdotes, logical rationale, and randomized controlled trials, the last of which should be given more weight because they’re controlled. If the hip thrust has worked well for you, recall that there are large individual differences in response to training.

Humans are biased. Let me state this more firmly: every human being on the entire planet is inherently and extremely biased. Our brains can’t help it. As the inventor of the hip thrust, even if I try to be the best scientist I can be, I’m going to view hip thrusts in a favorable light when possible. My loyalty, however, is to science, not to hip thrusts, any financial interests in the Hip Thruster, or any future invention I may develop. When evidence emerges, a good scientist flows with the research; he does not dig his heels in and stubbornly cling to his long-held beliefs. Based on the latest research, barbell hip thrusts performed off of a bench as a sole lower body exercise do not appear to benefit sprinting speed in adults. Future research will determine if explosive hip thrusts with greater range of motion are beneficial for sprint speed.

Hi

Very honest words. we are only human and sometimes we can go wrong.

” If it is found that hip thrusts effectively build the glutes, then we need to figure out why this increased glute mass is not translating to faster sprint times…” – maybe it’s a matter of muscle balance which affects badly on hip flexors – reducing legs speed forward??!

Great write-up Bret. Appreciate to see you admit you went a bit too far on social media (who wouldn’t?) and break out the news. I’ll share in our bodybuilding science newsletter this week. Cheers.

You said that you made mistake.

You said that you now know that.

You said that you will try to see if there is some way that HT gains can have transfer to speed.

You are a very big person and I am proud to see how you are coping with the findings !

For all what you showed to us I must say “Thank you”.

For all what you will show to us in years ahead ” Good luck”.

Coach Ivan

In reference to your colleague Chris Beardsley, in one of his latest intsagram posts, hie referred to a study that purported that the ratio of gluteal muscle and hamstring size and power in comparison to quad volume and strength has a negative correlation. Maybe minimizing direct quad stimulus exercises would maintain a larger ratio difference, thus keeping the power differential intact or increased, improvement in sprinting speed may be realized.

In sprinting as well as other track events, the quads are accelerators not power generators; large quads may interfere with full expression of the hamstrings and glutes.

Bret – good job with the honest critique of yourself and a great summary. I know there are studies that say that if you are relatively fast but relatively weak, you can improve speed by getting stronger and if you are relatively strong but relatively slow, you can improve speed by training speed. Maybe a study that takes these groups these types of people can be helpful in making a point. I know Stuart McGill talks about timing and motor control with abs, not just abdominal strength, playing an important role in low back pain. It can be similar in this sense – maybe the thrust is giving people the tools to be faster, they just need to learn how to integrate it in their motor control!

This is an incredibly honest evaluation of your “pet” exercise and that is admirable. Though, and you mention this yourself, the methods used in the studies (to me) invalidate them at least a little in the context they were used. There’s two reasons for this to me and you touched on one of them, which was that they trained them incorrectly for the goal. The second being overall volume.

If you’re training hip thrusts for the sake of improving Sprint speed then your 1RM means nothing so the fact that their hip thrusts strength went up means very little. Training the hip for power and speed means doing them for triples at a lower percentage with more sets, and possibly or hopefully using accommodating resistance. (At least once a week, maybe twice with how much frequency can be safely used with them)

The lack of volume also hurts the validity. It’s one thing to use squats as a stand alone exercise and not use a massive amount of volume, but for Hip Thrusts you need (and can use) more volume. The overall systemic affect of hip thrusts are much lower than with squats or deadlifts which means that the recovery is faster even at higher volumes. This means that it would be prudent to use high volumes/frequencies with them as a stand alone exercise. The lack of overall volume hurts one of the hip thrusts major selling points and to me makes poor use of the movement.

I could be completely wrong in my assessment, you are the master after all, but that’s what I thought when reading it.

Cheers!

Mathiah

Good thoughts, but I wouldnt dismiss the findings due to “low volume” and “1RM means nothing”. What brings you to these conclusions? Sure, you can always improve on your training, but a 1RM means something. After all, its not the training per se, but the effects of the training that influence running speed. So higher volumes and frequ may very well be better suited for the HT – but 1RM did change considerable after all!

It usually is accompanied with improvements in RM at lighter loads (5/10/15 RM as examples) as well. And strength means something, because most non-elite sprinters are not yet maxed out in the strength department of the v-s-curve of hip extension – so more strength should be effective.

I’m still going to keep performing my hip thrust in hopes of improving more power in my golf swing as I know that the glutes are the engine which drives the swing. Besides as an older female lifter with 20+years of a heavy barbell on the back of my neck, I can no longer handle that load on my spine due to severe cervical DD. This industry is a continual learning process of trial and error and I know you will keep up on the research, which is much appreciated.

Kudos for your honest assessment, recognition and identifying your biases (we all have ’em). And it will be interesting to see hypertrophy results. I still think it’s an effective hip extension exercise and one of the least likely to be cause injury. In the end (haha!) you can never go wrong having stronger glutes.

Bret, thank you for your constant efforts and your commitment with the truth in your work. I read your articles often and I can always build upon your findings and apply them to improve my everyday training, consciously improving my knowledge also – which is not the case for the large portion of the (inconsistent) bro science found on the internet.

These fellas may not have had improvements of sprint speed but they sure have a better booty now

I appreciate this article. I have been using this exercise for the past couple of years and have been skeptical due to the fact that i haven’t seen the changes that were being reported. Now if the Skorcher solves this then I would love to have a couple in my gym but lets see that research. Until then I am going to squat and jump and teach mechanics, etc.. to help improve speed in my athletes

Firstly , congrats on your openmindedness and your scientific approach to hip thrust.

Some points of contention.

1. Fitness junkies and physique athletes been having muscular and full , shredded glutes way before the hip thrust , so i don’t think the exercise is so much better for muscular development that glute ham raises or back extensions. After all , to the trained eye , a movement , like hip thrust , that can be loaded heavy even the first time u do it , is a little suspicious. I see untrained women get to 150 kg for 8-12 reps in 3-4 weeks of training , the very easy load progression takes a lot of the credibility of the movement away.

2. That being said , i am intrigued as a S&C coach in football , by the movement itself , done with proper variable adjustment (not worry about eccentric portion , lift submaximal to 1RM loads with maximal speed intent.).

My opinion , i don’t care about the research , in 7-8 years maybe and 30 sth papers on athletes later we revisit the subject. Hip thrusts are MADE for athletes , they don’t lend as much to physical development. If in 2 years u get an athlete to lift 150 kg more 1Rm in hip thrust , he is going to be faster , hip extension torque will be bigger , that’s common sense after all , don’t need to be a rocket scientist to assume that…

1. Easy load progression takes nothing away and neither do starting weights have anything to do with the “credibility” or effectiveness of an exercise. According to that rationale, deadlifts are super-suspicious, where wrist curls are not. It does have something to do with biomechanics: resistance curves, muscle mass and in the case of the HT with the fact that the glutes are heavily undertrained in most trainees.

Bret, this is one of the best articles I have read in awhile. My respect for you as a trainer and, I think more importantly, as a researcher has just elevated. Whenever you are in the MA area, especially if you visit Cressey Sports Performance, where I have been known to train with the crew as my schedules allows, it would be a pleasure to meet and chat with you. Keep being real.

Excellent article Bret! Thanks!

Your friends at FP gunna run with this. They will be so excited haha

Training studies are always tricky to translate to “real life”. Training studies implementing ONE rather strong stimuli is very different from regular training that is always very complex in nature. If hip just hip-thrusts alone successfully are able maintains sprinting ability for a 8 week without any other stimuli I would not be too discouraged, quite the opposite in this case.

We’re the study protocols ideal? How about the control group practices sprints only, and the other group practices hip thrusts and sprints concurrently? Also, you make a fair point- these athletes might have already reached their “genetic limit” on sprints…

A foolish man rarely questions and is full of certainty, a wise man questions lots and is full of doubt. An excellent, honest, introspective and more importantly scientific piece. Well done Brett, if more social media fitness gurus followed your lead the fitness industry would be a better placentre!

your articles, honesty and integrity are the very best on the net

Interesting stuff here, no doubt. I really enjoyed the honesty and transparency here Bret. Although I can’t give actual % improvement in my groups before and after we started doing hip thrusts (due to lack of recording), I can tell for sure that hip thrusting made a qualitative and quantitative impact on myself and my sprint athletes in the NCAA DIII setting. We didn’t even get that heavy with the lift (as you mentioned in our podcast… it doesn’t always take too much weight). In the years that follows those sprint PR’s (I had multiple athletes hit lifetime sprint PR’s after a month or so of hip thrust intregration), I started to really take my own hip thrust to its limits, as well as pushing more limits in the DI college athletes I now coached. I started to get that feeling that past the initial benefit of better muscle coordination in the glutes (muscle coordination that had to be infused on the day-to-day planning alongside sprinting very fast), just taking someone’s hip thrust super high didn’t really help speed. It seemed like a low, proper dose, alongside a good speed program really did yield solid benefits. It would also make sense that improved glute strength might be more directly “downloadable” right into the motor programs of young athletes, where for older athletes with more established and hardwired sprint and jump programs, simply making a muscle stronger may be of less benefit than for a younger athlete… especially if those older athletes weren’t doing a lot of hard sprinting alongside the hip thrust programming. Principles that can be adapted for any lift. I just read the abtracts of the no results research, I’d be interested in more knowledge about them, but I’d say as a general rule, ANY weightroom lift, devoid of integration into a good sprint program will yield limited results, especially in more developed athletes. Keep pushing the industry forward Bret, appreciate articles like this keeping things fair and unbiased.

Great article Bret. Really great.

We are weakest at the shortened end of a muscle. It’s called active inefficiency. Look it up. Hip thrusts, especially when you add bands and weight, train the weakest range of the glutes. That’s why it’s easy in the beginning and hard as heck at the top!!!! So in other words, it’s a backwards exercise. Hip thrusts can be used to train one end of the range but in no way should be the majority of hip extension exercises. If you want an exercise that isn’t backwards like the hip thrust, try a back extension/hip extension machine – if done correctly it’ll get easier where the glutes get weaker. It’s nothing new, it’s just logical training.

Hey Bob, I don’t need to look it up…I’ve been educating people about active insufficiency for years. Maybe you should look up my prior articles. I’ve never said that hip thrusts should be a majority of one’s training and have always recommended a combination of glute exercises for maximum results.

But why would it be a “backwards” exercise? If you go to the hip thrust wiki page, you’ll see emerging research from Ian Bezodis showing that hip thrusts don’t involve the greatest moments at end range hip extension – this is according to 3D motion analysis software and force plate data. So perception isn’t matching objective biomechanical data here.

Regardless, I understand the natural hip extension torque angle curve (I wrote a product with Chris Beardsley called “Hip Extension Torque” and conducted research on this and got mine measured; we’re 2.5X stronger in full hip flexion compared to full hip extension – so what?), why wouldn’t you want to be maximally strong throughout the entire ROM? Perform some movements that stress hip extension strength in deep hip flexion (squats, deads, lunges, good morns, etc.) and some that stress hip extension strength in end-range hip extension (hip thrusts, back ext’s, 45 deg hypers, bridges, etc.). Especially since the latter group activates markedly more upper glute max fibers in addition to lower glute max?

And I don’t think one exercise or machine can work well for everyone as our anatomy differs. The back extension/hip extension machine won’t perfectly match the human internal hip extension moment angle curves nor will it build glutes like hip thrusts due to less activation/metabolic stress or squats due to less muscle damage. Variety is the spice of life.

“…. as a prolific S&C educator….”

Dude, I love your stuff but this ego-stroking you always throw into your articles is lame and self-gratifying. Besides that, solid article and appreciate the honesty.

Well, I wasn’t trying to be cocky. Prolific means, “present in large numbers or quantities; plentiful.”

I have have like 600 blogposts, 44 published journal articles, 2,000+ IG posts, etc.

Prolific doesn’t mean “great,” it just means plentiful, which aptly describes me.

Great words. I love you’re work. Thanks to you’re original research and I remember your posts all through you’re thesis…I was able to use variations for my personal ongoing maintainace of FAI. I can say that it has worked for me. It’s one of the last exercises I can do and still maintain a decent ass, and put off surgery so far.

I appreciate you’re sincerity but don’t beat yourself up, there’s something there that’s working. I am one of the people it has helped. Mahalo Claudia

We really appreciate your honesty and integrity Bret, that’s one of the reasons why we trust you. Well done, and keep on with your great job!

I just started hip thrusts since we one day I saw a new hip thruster in my gym. None of the topics discussed really apply to me, but I’d say it does help with the squat. I just do some light ones to get some glute activation going since I sit most the day at work and at home. I think it’s a great exercise for glute activation. There are other way to do it, but this method is certainly the fastest and targets the glutes really well in my opinion. Plus aesthetics don’t hurt either!

What was the power of the 2 studies. Is the sample size not too small? It appears the participants did not include any dynamic running training, and so the gain in muscle strength did not transfer to the functional task of running. Can we have studies of 2 groups : Group A – hip thrust + running, Group B – Only running and let’s see if the addition of the hip thrust to group A will be better than just running. We know muscle strengthening does not automatically lead to greater functional gains if you don’t incorporate the increased muscle strength into a functional activity.

Are the donkey kicks/quad rupped kickbacks the same as a single leg hip thrust? They look very different in form but when you look closer the glute is performing in almost the exact same motion? Would you agree or disagree and is there any point doing both? If they are so simlar?

Do you think kickbacks are more sport specific for sprinting than hip thrusts at least for the early phase of the sprint out of the blocks?

Do you think kickbacks would have much better speed gains than hip thrusts because they are less an isolation movement and more a compound movement a sport specific compound movement?

They’re indeed similar. I would call them unilateral anteroposterior hip extension exercises. But the thrust is closed chain and the kickback is open chain. I would advise doing both throughout the year but yeah they’re probably redundant for sprinting purposes. I don’t know which would be better…I think the thrust is slightly better for hams and the kickback slightly better for glutes.

cool thanks for your overly advanced response xD

Its funny when someone has knowledge levels way above the norm and they make your question redundant before then answering it lol

Ive always wondered why you are the self proclaimed inventor of hip thrusts yet they are in Super Training. You didnt think them up

I’m not the “self-proclaimed” inventor…everyone who is anyone in this industry knows I invented them. If you have any evidence of anyone performing barbell hip thrusts prior to my arrival, then please let me know and I will credit the rightful inventor. I did think them up. I found pics of them in Supertraining long after I started doing them, and they’re partner resisted…not barbell. Far different.

he did, when someone talented comes up with an idea a bunch of low moral half wits try to take credit for it and steal your ideas to make cash. A lame part of human nature.

Very honest and smart post, congratulations!!

Hey Bret,

How about a scortcher esque attachment to the hip thruster. It seems like a simple solution would be to use some sort of pipeing that could clip right on to the out riggers where the bands attach. Let me copyright this odea real quick :p.

Dr. Jay

Been thinking about this…

excellent post !

Watson Gym Equipment in the UK make a machine that looks very much like your Skorcher . . . maybe you are due some royalties 💵💵💰💰

Those shitheads never even reached out to me…they were the very first to knock-off my Skorcher. The least they could do is send me a free unit LOL, they made my hip thruster much better 🙂

Great article Bret! Very honest! Keep up the great work! Cheers.

So much appreciation. Thank you!

Your honesty doesn’t go unnoticed. In a field where advertising misdirection can be key to success, it’s refreshing to read material that holds this level of integrity. Thank you again!

Your statements about science impressed me as much as anything else about the article. I recall Daniel Shechtman, winner of the 2011 Nobel Prize for Chemistry. The untold story behind Shechtman’s accomplishment is that he discovered quasi-crystals in 1982, but this fundamental alteration in how chemists conceive of solid matter languished because of bias. None other than Linus Pauling derided and disparaged Shechtman’s discovery, reinforcing a paradigm that took decades to break down.

Your words, that we all have bias, can often be especially true for scientists.

In that light, an extra helping of kudos for your openness and honesty.

Hi Bret,

Greetings and thanks for discovering the hip thrust. Here’s my take: Sprinting biomechanics is a chain of neuromuscular events. A chain is only as strong as its weakest link. If increased glute strength didn’t improve sprinting, glutes may not have been the weakest link in the first place, especially considering that the select group consisted of athletes in the first place. For recreational/weekend players, glutes might have been their weakest link(may be why they didnt get to be elite ones). Plus, i think doing a lot of HT will strengthen the glutes to do just that. To take advantage of the increased glute muscles obtained from HT, you got to practise the functional exercise/sport(say soccer) to optimally condition the neuromuscular chain for that sport.

I haven’t read through other comments, so if i accidentally duplicated what anyone else has said here, my apologies.

WIsh you well Bret..

A hyper scientific approach from a meathead? 😝 It seems that you are changing the field of strength n conditioning Bret. Keep on the good work i m tired of the correlation people make between physical prowess and stupidity. Maybe they would be helped in discovering their biases by reading ur article 😉

Hello,

Maybe this was stated earlier, but did you consider that the adolescents gained more from hip thrusts due because they had not yet developed these muscles vs collegiate athletes who had worked on these muscles for years?

Could you do a study involving adults who had not previously trained to increase speed vs athletes who had?

Thank you,

Great integrity, makes me appreciate you more Bret!

Remark: as a former regular visitor of PT’s due to lower back issues (sport imbalances) I have been often recommended to do (unloaded) hip thrusts. So have many of my sports friends – hockey is a great sport… If that ‘science’ is convinced it is beneficial for at least that part of the population, and if anecdotally also their ‘patients’ are….

Question then indeed becomes: what are those benefits and consequently which demographics are to be targeted?

“Heavy Barbell Hip Thrusts Do Not Effect Sprint Performance”

“Effect” should be “affect” here. Either that or “Heavy Barbell Hip Thrusts Do Not Effect Sprint Performance Improvements”.

I like the fact that you recognize the limitations of the hip thrust for improving sprint speed, although I did express my doubts in relation to this from my own anecdotal experience as a sprinter a few years back. A post approximately 2-3 years ago.

Speed is a combination of factors, including relative strength/power and training methodology, stride length, cadence, muscle length, sprint mechanics, with the ability to accelerate the lead leg into the ground during stance phase creating greater RFD, and execution of the different sprint phases. Not to mention FT muscle fiber ratio’s and muscle endurance, and muscle contraction/relaxation sequencing and sprint training methodologies. There’a an awful lot of contributing factors, of which maximal strength through any given movement pattern is of little contributing significance.

Quite simply, in my experience, sprint speed can be improved through training, but the scope for improvement on natural ability is limited. World class sprinters are born and mediocre athletes cannot become world class. Myself included, being a mediocre sprinter attaining a 10.8s for the 100m. Having trained with sprinters who are world class, at 10.3 and below. That’s 10.3 being their natural speed without much training and progressing to 10.1 and below. My own natural ability was around 11.5s improving to 10.8s with relatively limited training.

The one thing that I noticed was that I was much stronger in the gym than guys who were faster than me, even for relative strength, but they could still out sprint me. Although the difference was only from about 30m to 40m onwards.

Again, from my anecdotal experience, I would say that pretty much all improvements in the gym translate to the first 30m-40m only. After that, you pretty much have to be genetically predisposed to fast sprint times via natural selection. i.e Gifted.

If we are going to make the claim that science is ‘self-correcting’ we should also examine the limitations and biases of science.

Personally, I think it is hogwash that glute thrusts don’t increase speed if that is a goal of the practitioner. The reason is that we are human beings, not robots. Our physiques, and how we feel and how our muscles activate change our behavior. If you have strong glutes and hams and activate your posterior chain and think of yourself as fast and want to run, you will probably behave differently in the real world and actually get faster. The value of these studies may be limited because they take an inherently muti-dimensional behavioral model and try to isolate just a few variables so that you can get a paper published.

I am much more inclined to believe your original naturalistic understanding of how things have unfolded with the people you work with than isolated studies conducted for publication.

In the field of cognitive science, there is a parallel here I believe. Look up Gary Klein, who looks at naturalistic choice models and macro-cognition versus the typical controlled cognitive studies conducted through isolating variables.

For a look at the terrible record of scientific papers:

https://goo.gl/vhXJZT

Gary Klein – Macrocognition:

https://goo.gl/BwFcXq