This article is a very important read for any individual who works in the strength and conditioning and sport training professions. It is my hope that the terminology described within this article will catch on and appear more often in conversation and literature. Please read this article and decide for yourself which language you will proceed to use when describing movement..

Planar Terminology

In the sport-specific training profession, it’s very common to hear coaches utilizing planar terminology to discuss movement. You might overhear a strength coach saying something like, “I like this exercise because it’s multiplanar,” or, “this exercise is great because it’s a sagittal plane movement that requires stabilization in the frontal and transverse planes.”

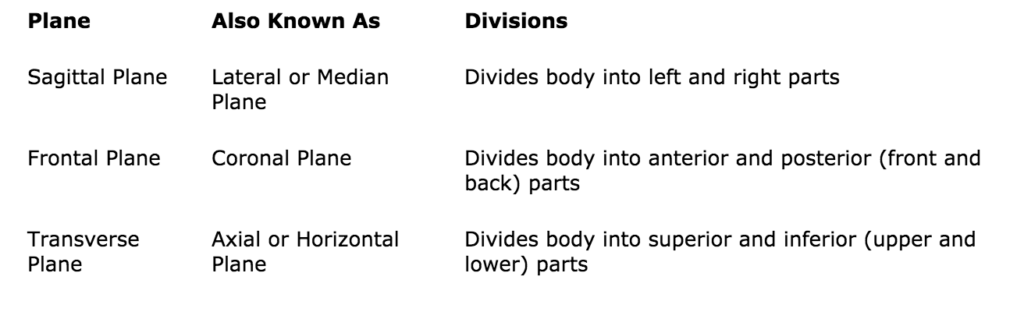

There are three body planes (body planes are sometimes called anatomical planes or cardinal planes), which are imaginary lines that divide the body into two parts:

In case you didn’t know, a Turkish get-up would be considered multiplanar since it combines movement in the transverse, sagittal, and frontal planes. A squat is a sagittal plane movement that requires stabilization in the frontal and transverse planes, since the knees tend to want to cave inward and enter into a valgus position (adduction and internal rotation of the femurs), which requires proper firing of the hip external rotators, mostly in the transverse plane. If you look at the diagram below, you’ll be able to envision how a lateral raise or jumping jack is a frontal plane movement, a pec deck or a baseball swing is a transverse plane movement, and a crunch or a lunge is a sagittal plane movement.

While planar terminology is a great start, I believe that we can do better. Planar terminology is too general, which is why we need force vector terminology. Force vector terminology is more specific to movement. Our profession borrowed planar terminology from anatomy language, but gross anatomy doesn’t consider movement. Force vector terminology is used often in engineering, and a vector contains both magnitude and direction.

What’s the Point in Using Force Vector Terminology?

Although I feel that strength coaches should still use planar terminology depending on the situation, I believe that strength coaches should also be well versed in force vector terminology since there are plenty of situations where force vector terminology is more appropriate and descriptive.

Why is planar terminology insufficient? In planar terminology, jumping, running, and backpedaling are all sagittal plane movements, even though they are completely different. One of these actions has you moving upward, one has you moving forward, and one has you moving backward. Force vector terminology corrects these terminology deficiencies and allows us to better describe movement.We can use force vector terminology as a way to categorize exercises, describe movement, assess strengths and weaknesses, and choose exercises that may transfer ideally to sport.

Force vector training takes into account the line of pull, or the direction of the resistance, as well as the position of the exerciser’s body in space when they are directly opposing the resistance or line of pull. The easiest way to determine a force vector is by using images to show a graphical representation of the direction of resistance (via an arrow) in relation to the human body.

Basic Force Vector Terminology

• Posterior – toward the back (sometimes synonymous with dorsal)

• Lateral – toward the side (away from the midline)

• Medial – toward the middle or midline

• Superior – upper or above

• Inferior – lower or below

• Axial – top to bottom

• Torsion – twisting or rotating

• Anteroposterior – front to back

• Posteroanterior – back to front

• Lateromedial – outside to inside

The Six Primary Force Vectors in Strength Training and Sports

Here are the six primary force vectors I see in the weight room and in sports:

1. Axial

2. Anteroposterior

3. Lateromedial

4. Posteroanterior

5. Torsional

6. Axial/Anteroposterior Blend

Force Vector Terminology: Off to a Good Start, but Still Much Room for Improvement

We could certainly be much more technical if need-be. For example, true axial lifts produce compressive forces and wouldn’t include exercises like chin ups, which produce distraction forces. Now, muscular tension creates compressive forces, so a chin-up will still compressively load the spine, but I digress. Nevertheless, if we wanted to be more accurate, we would need to split axial into superoinferior and inferosuperior, and we’d also need to split lateromedial into lateromedial and mediolateral. However, in my model, I lumped them together for the sake of convenience. Another possibility to “clean up” the axial terminology is to use “axial positive” for compressive exercises such as squats and overhead press and “axial negative” for distraction exercises such as chin ups.

Furthermore, I like to consider all horizontal pressing as anteroposterior force vectors, yet depending on the body position (prone vs. supine), the force vector reverses. For example, a push up is technically posteroanterior, while a bench press is anteroposterior. The same can be said about horizontal pulling; an inverted row is anteroposterior while a prone bench row is posteroanterior. Finally, the same could be said for horizontal hip dominant lifts; a hip thrust is anteroposterior while a reverse hyper is posteroanterior. For the sake of simplicity, I lump all horizontal pressing into the anteroposterior category, since the intent is always to push forward via shoulder flexion/horizontal adduction. I lump all horizontal pulling into the posteroanterior category, since the intent is always to pull rearward via shoulder extension/horizontal abduction/scapular retraction. Finally, I lump all horizontal hip dominant lifts into the anteroposterior category, as the intent is to either push the hips forward or to pull the thigh rearward via hip extension/hip hyperextension.

You might be wondering why there’s an axial/anteroposterior blend. This distinction is necessary because it separates acceleration sprinting from max speed sprinting, as well as certain exercises and plyos that are blends of both vectors. This is important, since optimal training for these types of sport actions might require specific exercises as well as a balanced blend of axial and anteroposterior vector exercises. Of course, we could create more blends to describe different sporting movements, as truly every combination of force vector exists.

I should mention that in sports there is often no external load – often the individual is simply propelling his or her own bodyweight. In this case, you’d want to consider the resultant ground reaction forces. Sometimes it can be confusing when determining vector terminology and considering the potential transfer of training from the weightroom over to sports performance. For example, when an individual is sprinting, he or she is moving his or her body forward, which would be posteroanteriorly. If he or she is leaning forward during acceleration, then there exists more of an axial component (as alluded to earlier). Now, axial forces will exist in sprinting due to gravity and the need to raise the body’s center of mass, however, horizontal forces have been shown to be more correlated to sprinting performance than axial forces. Therefore, if we mimic this vector in the weightroom, we must apply a load in that direction. If we put a bar on the hips and do a supine barbell hip thrust, or if we pull a sled with a fairly upright stance, then the direction of the load is anteroposterior. However, if we use a pendulum (such as getting on all-fours underneath a reverse hyper machine) to perform a loaded quadruped hip extension, or if we hold onto a dumbbell during back extensions, the direction of the load is posteroanterior. To rectify this, I believe it’s okay to oversimplify things and refer to sprints, hip thrusts, pendulum quadruped hip extensions, and back extensions as movements that train the anteroposterior vector.

Axial Force Vectors (Includes Superoinferior and Inferosuperior)

• Squat Variations

• Deadlift and Good Morning Variations

• Olympic Lifts (Clean, Jerk, and Snatch Variations)

• Single Leg Squats: Static Lunges, Bulgarian Split Squats, Step Ups, Pistols

• Vertical Pressing (Military Presses)

• Vertical Pulling (Chins Ups, Pull Ups, Upright Rows, Shrugs)

• Barbell Curls

• Vertical Jumping, Vertical Plyos, and Jump Rope

Anteroposterior Force Vectors

• Single Leg Glute Bridges and Single Leg Hip Thrusts

• Barbell Glute Bridges and Barbell Hip Thrusts

• Pendulum Quadruped Hip Extensions and Cable Pull Throughs

• Back Extensions and Reverse Hypers

• Nordic Ham Curls, Glute Ham Raises, and Slideboard Leg Curls

• Bench Presses, Push Ups, and Standing Cable Presses

• Pullovers

• Planks, Ab Wheel Rollouts, Bodysaws, and Hollow Rock Holds

• Max Speed Sprinting and Bounding

Posteroanterior Force Vectors

• Band Resisted or Barbell/Dumbbell Forward Lunge

• Backward Sled Drag

• Seated Rows, Inverted Rows, Hammer Strength Rows, One-Arm Rows, Standing Cable Rows, and Face Pulls

• Backward Hops and Backpedal Sprinting

Axial/Anteroposterior Blends

• Walking Lunges

• 45 Degree Hypers

• Kettlebell Swings

• Pendulum Donkey Kicks, Reverse Leg Presses, Power Runner Machine, and Leg Presses

• Incline Presses, Decline Presses, and Dips

• Bent Over Rows, Corner Rows, and Chest Supported Rows

• Sled Pushes and Pulls (with lean)

• Farmer’s Walks and Yoke Walks (mostly axial, but you’re moving forward)

• Stadium Sprints

• Acceleration Sprinting, Forward Leaping, and Pushing an Opponent Forward

Lateromedial Force Vectors (Includes Lateromedial and Mediolateral)

• Side Lying Abduction, X-Band Walks, Sumo Walks, and Band Standing Abduction

• Lateral Raises

• Side Planks and Suitcase Carries

• Lateral Sled Drags

• Lateral Hops, Lateral Plyos, and Jumping Jacks

• Cutting from Side to Side and Carioca

• Slide Board Lateral Sprints

Torsional Load Vectors

• Pallof Presses and Anti-Rotary Holds

• Cable Chops, Cable Lifts, and Landmines

• Band and Cable Hip Rotations

• Tornado Ball Slams and Rotary Med Ball Throws

• Side Lying Clams and Band Seated Hip Abductions

• Pec Deck, Reverse Pec Deck, Flies, Prone Rear Delt Raises (Especially Unilateral Versions of These Movements)

• Swinging, Kicking, Punching, and Throwing

Force Vector Analysis Can Be Pretty In-Depth With Certain Exercises

Consider most anti-rotational exercises – say the Pallof press, the cable half-kneeling anti-rotation press, and the landmine. These exercises each possess both torsional and also lateromedial force vectors, meaning that they place axial twist loads on the body in addition to lateral bending loads. Therefore, these exercises could be lumped into a special torsional/lateromedial blend category. Consider the 1-legged Romanian deadlift with a dumbbell held in the contralateral hand. At face value, you’re lifting the load upward, so this is an axial movement. However, at the bottom of the lift, the torso will be receiving a posteroanterior load, since it’s bent over. Since the lifter is standing on one leg with the load in the opposite hand, there will be a combination of torsional and lateromedial loads on the spine and hips.

As you can see:

1. Often multiple force vectors exist within a single exercise

2. Force vectors can fluctuate throughout an exercise, and

3. Force vectors can vary according to different regions of the body during a single exercise and technically there’s at least a slightly different force vector acting on every single joint in the body during an exercise

Application to Sport-Specific Training

Force Vector Training (FVT) is not a specific type of routine that you can follow. It’s simply a model that you should keep in mind during programming to make sure you’re training the appropriate vectors and keeping balanced strength between different directional demands. Although force vectors are important considerations for all types of fitness endeavors, FVT has the most application to sport-specific training. Below are some bullet-points to consider.

• Let the sporting actions dictate the best way to train in the weightroom. See the pictures below. What do these pictures tell you? Consider the exact lines of decelerative and propulsive force for each activity. Then analyze which strength and power exercises follow similar patterns of force vectors.

• An athlete is always moving in one direction while stabilizing in the other directions.

• FVT blends together Physics and Functional Anatomy and the direction of force influences the torque-angle curves that are inherent to sporting and weightroom movements.

• Strength and power training according to the proper force vectors activates muscles in a similar manner (though often not at the same speeds) in which they activate during sporting movement. This is important.

• There is certainly appreciable overlap between the development of strength in various vectors. For example, performing heavy squats will likely transfer to every single vector. However, for maximal total vector strength, more specific means are likely necessary.

• Use all the tools available; bodyweight, dumbbells, barbells, specialty bars, kettlebells, resistance bands, chains, body leverage systems, cable columns, suspension systems, machines, sleds, battle ropes, medballs, Indian clubs, and landmine units.

Start looking critically at various exercises. Although most movements are beneficial and provide a training effect, start asking yourself questions like these:

• How would a static lunge have an axial vector whereas a walking lunge would have an anteroposterior/axial blend vector? At what range of hip motion does hip extension torque “shut down” with each movement?

• What is the difference between a good morning, a 45 degree hyper, and a back extension? Do they possess unique hip extension torque-angle curves? Which exercises loads the stretch position best, which exercise maximizes mean torque, and which exercise loads the end-range position best? Do they complement each other?

• How do force vectors impact accentuated regions of force development and positions of maximum muscular contraction? For example, in what position is the most difficult part for the glutes in a squat (axial loaded) – at the bottom of the movement (hips flexed) or at the top of the movement (hips neutral)? In what position is the most difficult part for the glutes in a hip thrust (anteroposterior loaded) – at the bottom of the movement (hips flexed) or at the top of the movement (hips neutral)? Would these exercises not complement each other to produce hip extension strength and power through a full spectrum of motion?

• Which implements are best suited for training specific rotary power; a landmine unit, resistance bands, dumbbells, cables, a barbell, a kettlebell, or a suspension system?

• During a side lunge, is the emphasis on pushing upward or laterally? Would a slideboard be better at training lateral power? Which requires more hip abduction and hip external rotation torque?

• Would a resistance band or a dumbbell be more useful for training punching power in terms of a jab? What about an uppercut?

• What implement would be better suited for training for rotary power for chop and lift patterns – a medball or a cable column?

• For forward deceleration and backpedaling power, would a forward lunge not better-replicate the demands on the knee joint than a reverse lunge?

• For vertical power production, could one not substitute barbell jump squats with dumbbell or trap bar jump squats? Could heavy kettlebell swings be a suitable replacement for power cleans and snatches depending on the situation?

• For sprinting speed and acceleration, should you use a weighted vest to provide more axial loading, or a sled to provide more anteroposterior loading?

Application to Bodybuilding/Physique Enhancement Training

• Let the muscle fiber directions dictate the best way to train a muscle part, muscle, or muscle group. See the pictures below. What do these fiber directions tell you?

• Hit the muscles from different angles, and perform some movements that target the stretch position, some that target the mid-range position, and some that target the contracted position.

Application to Powerlifting

• The force vectors for the big three lifts are: squat – axial, bench press – anteroposterior, deadlift – axial.

• Therefore, you’ll want to perform axial lower body lifts for specificity, such as good mornings and additional squat and deadlift variations, and you’ll want to consider including anteroposterior lower body lifts for additional posterior chain activation, such as hip thrusts, back extensions, 45 degree hypers, reverse hypers, and glute ham raises.

• You’ll want to perform anteroposterior upper body lifts for specificity, such as board presses, chain suspended push-ups, and chest supported rows, and you’ll want to consider including axial upper body lifts for additional delt and lat activation, such as military press and chins.

Application to Core Stability Training

To improve core stability, the spine, pelvis, and hips need to be hit from multiple vectors, since different muscles are used to stabilize the body depending on the direction of force. Consider the list below:

Developing Anti-Extension Core Stability through Posteroanterior and Anteroposterior Forces

Lifters need to develop the anterior core muscles including the abdominals and obliques, but they also need to learn how to perform posterior chain movements without hyperextending their spines, which requires motor control and glute strength.

• Posteroanterior core exercises: front planks, RKC planks, stability ball rollouts, blast strap fallouts, ab wheel rollouts, bodysaws, hollow body holds

• Anteroposterior core exercises: hip thrusts, pendulum quadruped hip extensions, back extensions, reverse hypers with neutral spine

Developing Anti-Lateral Flexion Core Stability through Mediolateral Forces

• Mediolateral core exercises: side planks, lateral sled drags

• Off-set/single limb axial core exercises: single arm lateral raises, single arm lunges and Bulgarian split squats, single leg deadlifts, single arm overhead presses, farmer’s walks, suitcase holds, and waiter’s carries

Developing Anti-Rotation Core Stability through Torsional Forces

• Torsional core exercises: Pallof presses, band anti-rotational holds, chops, lifts, landmines, weighted bird dogs, weighted dead bugs, cable hip rotations, stability ball Russian twist, single arm cable chest flies, one arm cable rotational rows, one arm rows, and single arm dumbbell bench press

Developing Anti-Flexion Core Stability through Axial Forces

• Axial core exercises: squats, deadlifts, and good mornings

Application to Conditioning

Use variety in conditioning. For example, many athletes are great at barbell circuits but do very poorly with band circuits, as they don’t have anteroposterior hip stability, strength, and endurance.

• Bodyweight complexes (good balance of all vectors if done correctly)

• Barbell, dumbbell, and kettlebell complexes (mostly axial)

• JC band and TRX system complexes (mostly anteroposterior)

• Landmine complexes, battlerope and Indian club complexes (great for vector variation and mediolateral/torsional vectors)

Circuits can include each of these implements for vector variety as well.

Application to Activation Work

Force vector consideration can be used to increase the activation for certain muscles or to accentuate the region of force development on initial range or end range contraction (stretch position vs. contracted position). Here are some examples:

• Feet elevated scap push-ups for increased serratus anterior activity (you want a strict anteroposterior vector)

• Face pulls (alter vector from high to low to target different fibers)

• Shoulder elevated glute bridges (hip thrusts) for increased quad and gluteus maximus activity (you want a strict anteroposterior vector up top in the contracted position), feet elevated glute bridges for increased hamstring activity

• X-band and sumo walks – upright for glute med and mediolateral vector focus, crouched with bent knees for more glute max and torsional vector

• Hip flexion – cable column for anteroposterior/stretch position emphasis, standing ankle weight for axial/contracted position emphasis

To most coaches, force vectors are obvious from an upper body standpoint. Vertical pressing will target the shoulders better than horizontal pressing, whereas horizontal pressing will target the pecs better than vertical pressing. Vertical pulling will target the lats, whereas horizontal pulling will likely bring in the mid-scapular retractors to a greater degree. Most coaches understand the difference in muscle activation as it pertains to core exercises as well, as the various spinal flexion, spinal lateral flexion, spinal rotation, and spinal extension (whether dynamic or static) exercises allow us to feel the various muscles working differently. However, many coaches do not possess an adequate understanding of force vectors as it pertains to hip extension. Most mistakenly believe that hip extension is hip extension, that anteroposterior hip extension exercises shouldn’t be loaded up, and that bridging is merely a way to “isolate” prior to “integration” to teach glute activation.

If the direction of the force vector didn’t matter, then we’d prescribe squat motions for glute activation rather than bridging motions. Bridging motions activate more glute than squatting motions at equal loads. For example, a bodyweight bridge might elicit three times as much glute activity as a bodyweight squat, as might a 300 lb glute bridge over a 300 lb squat. Bridging motions strengthen the glutes in a more “hips-extended” position, which is a critical range in sports as that is the precise range at ground contact during a sprint (and the range that yields the highest level of glute activation in a sprint). Don’t be afraid to load up this pattern and go heavy.

Application to Assessment

It’s important to be strong, stable, and ultimately powerful in all directions. Often someone can possess great movement efficiency in one vector and poor movement efficiency in another. This is one of the reasons why many coaches like to say, “Everything is an assessment.” Literally every exercise and activity an athlete performs provides clues as to how strong, mobile, and proficient he or she is in the various movement pattern or vector.

An individual may perform a squat pattern very well but struggle with a bridging pattern. For example, I’ve seen individuals who can squat over 400 lbs but struggle to perform simple bodyweight bridges. These same individuals tend to struggle with proper technique during back extensions and reverse hypers. Their axial proficiency is sound, but their anteroposterior proficiency is not. This might be due to the fact that they have good hip flexion mobility and hip extension strength in flexed positions, but perhaps they have weak end range hip extension strength or poor motor control in the glueus maximus at this range of motion. The converse is true as well; sometimes an athlete possesses incredible strength and technique with anteroposterior hip extension exercises but not so much with axial hip extension exercises.

Furthermore, I’ve trained female athletes who could squat and deadlift very well, yet struggled with a 20-lb Pallof press (the lightest weight on the cable stack). They possessed sound axial efficiency, but their torsional efficiency was lacking.

During the actual strength and power training portions of the session, you will be provided additional clues as to how strong or powerful an athlete is in a typical vector. If they possess a glaring imbalance in strength between the various vectors, they’re likely leaving some room on the table in terms of athletic prowess. This is especially true for certain sports that rely heavily upon certain vectors for power.

It is quite possible to be strong at the hips and core in one vector but weak in another. Gluteus maximus strength in particular seems to be vector-specific as its role in hip extension, hip hyperextension, hip abduction, hip transverse abduction, hip external rotation, and posterior pelvic tilt may require exercises from each of the axial, anteroposterior, mediolateral, and torsional vectors. Sure, simply developing muscular glutes will go a long way in allowing for multi-directional glute power, but for maximum power in all directions, a multi-vector approach to glute training is likely necessary.

Of course, you always need to consider all possible vector weaknesses and take into account anthropometrical information a well. Does the athlete do poorly on a various moment simply because his or her body isn’t well-suited for the lift, or because it’s a new movement and they haven’t had a chance to learn the form, or are they truly weak in that vector? Sometimes you’ll need to test a couple of different exercises to get an accurate viewpoint.

Popular single leg exercises from various vectors challenge the torsional and mediolateral vectors’ stabilizing mechanisms and involve crucial muscles such as the adductors, gluteus medius and minimus, gluteus maximus, hip external rotators, quadratus lumborum, multifidi, obliques, and erectors, which need to be strengthened and coordinated for proper movement efficiency and power production.

Application to Overall Health

Here are some important considerations for LVT as it pertains to overall health:

• Strong Body – Your body needs to be well adapted to all directions of force for functional strength and work capacity. Too much emphasis in one force vector without enough work on other force vectors will yield sub-optimal results and fail to produce a well-rounded, athletic individual.

• Wolff’s Law of Bone – Bone adapts to become stronger according to the lines of force placed upon it. We want bone to be strong from all directions.

• Davis’ Law of Soft-Tissue – Soft-tissue adapts to become stronger according to the lines of force placed upon it. We want soft-tissue to be strong from all directions.

• Strength/Power – General strength development through the big basic exercises such as squats, deadlifts, bench presses, bent over rows, and military presses will develop an impressive athlete, but the athlete could be ill-prepared from a neuromuscular standpoint for anteroposterior, mediolateral, and torsional activities in sports. Certainly, plyometric, agility, and speed training aid in developing well-rounded power, but a balanced resistance training regimen is highly beneficial as well.

• Fun! – Quite often the best program for an individual is the one with which they’ll be the most consistent. Athletes and lifters have more compliance when they enjoy their routine, and they usually enjoy variety. Vector variety not only provides for a more effective workout; it provides a more fun and enjoyable workout as well.

How to Mimic Load Vectors

Think like MacGyver. He was a crafty individual. Use your knowledge of Biomechanics and all the training tools at your disposal to target the various directional force vectors.

• When using barbells or dumbbells, standing lifts usually target axial vectors, supine lifts usually target anteroposterior load vectors, and prone lifts usually target posteroanterior load vectors.

• When using bands or cables, standing lifts usually target anteroposterior or posteroanterior vectors, while supine lifts usually target axial load vectors.

• Performing unilateral variations of axial lifts tends to increase the mediolateral component (think single arm dumbbell overhead press), while unilateral variations of anteroposterior lifts tend to increase the torsional component (think single arm dumbbell bench press).

• Get creative: change body position, change the angle or line of pull, elevate a part of the body, etc.

Conclusion

I hope this article has given you some food for thought. Anytime you hear someone in the fitness field using planar terminology, smirk at them and say in a snooty voice, “Hmm. Planar terminology. That’s so 2000!” Then teach them force vector terminology. Of course, I’m being facetious as I still use both types of terminology depending on the topic and audience, but I make sure to consider force vectors when designing programs. It should be mentioned that there currently is not much research supporting the inclusion of force vector training. FVT is a theoretical model that would require a great deal of longitudinal research to support it. Axial lifting in the form of squatting and the Olympic lifts have formed the backbone of strength training over the past several decades for good reason – they’re highly effective in developing total body strength. However, they alone will most probably fail to maximize an athlete’s strength, power, and conditioning in all vectors. The better understanding you have of force vectors, the better you’ll be as a lifter, trainer, coach, or rehabilitation specialist.

Phenomenal post Bret! I can see the math teacher coming out 🙂

From a balance and symmetry standpoint, this terminology can be very useful. Admittedly, confusing at first, but so were the three anatomical planes when I was in college.

Thanks!

Thank you Jaison! I agree completely. Confusing at first, but begins to make much more sense over time.

Great stuff Bret. I have been thinking about this a lot lately, particularly what you’ve noted as lateromedial and torsional vectors for sports performance.

In fact I wonder if what you’ve listed above is comprehensive enough regarding the lateromedial vectors. I’m still thinking about it, but I’m wondering if we need more lateral lunges and squats, or maybe some time of lateral sled work to get the adequate angles?

Anyhow, glad you’ve started the dialogue!

Thank you Elsbeth! I’m glad you mentioned lateral lunges as I don’t like them very much for lateromedial. I feel like they’re still “axial” oriented. However, I totally agree regarding lateral sled work and don’t know why I failed to include them in my list. I’m correcting that right now and adding them to the list. Great comment!

Cool! Ya, I agree the lateral lunges don’t get the right vectors. But I think we need to do more work on that vector. I think that’s why I still like bilateral squats – for the angles. I also wonder if there’s a need for combinations of torsional and either axial or lateromedial. Maybe it’s getting too specific, but I’m starting to think about the importance of energy leaks and efficient transfer of energy from upper to lower body and vice versa and I think in most sports, it rarely happens in either the x, y, or z axes – it happens in a combination of them.

Elsbeth, for the reasons you mentioned I believe that the landmine is an amazing exercise. You get axial loading since the weight is out in front, you get lateromedial loading when the weight is off-centered, and you get torsional loading as you rotate the bar. I know Mike Boyle focuses on short ranges of motion for core stability which is an effective way to do them. Another way to do them is like I do them in this video. I don’t think there’s any considerable lumbar ROM to be concerned about but I like the explosiveness in the second method shown:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-QngxNVwqEM

This article is gold!

Well i just got some brilliant ideas for vertical jumping after reading this article.

So a running two legs jump, is a blend of force vectors??

For the application of LV to activation work and weak link strengthening to the hip flexor in the top range like in sprinting.

What would be and advanced variations/exercises to use? beside from the sitting elevated knee demonstrated by kelly baggett and the standing one by mike boyle??

I still have more questions,but i will drop them later.lol

Thanks bret.

Yes, a running jump is axial and anteroposterior. I would say that in sprinting the hip flexor needs to be strong in both the stretch position and end range position which is why it’s good to do Bulgarian squats or static lunges (as these regions will maximize hip flexor EMG activity for the rear leg which is in the stretched position) and cable or band hip flexion for the contracted postion.

I like it! Have you tried it with adding some leg movement, so that you explode into it as a full body movement? And then maybe adjusting stance angle relative to the landmine. Part of me thinks there’s a point where we are getting too complicated, but the other side of me thinks if we can do better then we should. Strong is still strong, but I think sport is about application and transfer of strength at angles.

Yes I have. In fact, I believe I wrote about this last year in a TMuscle article called “Operation Barbell.” Basically, you rotate about the forefeet in order to get some hip external rotation (and hip internal rotation with the other leg) into the movement while sparing the knees. This might also help decrease the likelihood of resorting to lumbar rotation. Many times I “overcomplicate” things and end up dismissing them later on, but out of this “overthinking” process often comes brilliant concepts that stick.

Great article!

There seems to be a lot of emphasis on activation, assessments, screens, etc… nowadays. Wouldn’t participation( assume great technique across the board ) in a well designed program that embraces the concept of variation through different load vectors be enough to iron things out over the long term? I understand the need to determine a starting point and knowing your audience, so to speak, but doesn’t the training itself provide the ultimate assessment?

Would you use this as a tool to determine what an athlete shouldn’t do or at least shouldn’t do in-season? Is there a point when too much single leg work or load vector specific work becomes detrimental?

Rich. The answer to your question is yes. However, often people have glaring issues that can be cleared up more quickly using corrective strategies. For example, let’s say a person has poor ankle mobility and crappy glute activation. You just have them squat each week and work on improving their form. Over time their ankle mobility will improve as will their glute activation. However, you could get them there more quickly by having them do some ankle mobility drills and glute activation drills.

But your broader point about the training is an excellent point. If your program has a good balance of vector variety then your muscles and joints will receive the proper stimuli as long as you understand exercise progressions and regressions.

Yes, there is certainly a point where too much single leg work or axial work can become detrimental. It’s all about balance! This cannot be emphasized enough.

I was most interested in your Application to Powerlifting, as I am training for my first competition right now and am looking for the best type of exercises to maximize my performance.

Jia – Here’s my take on Powerlifiting. You obviously need to squat, deadlift, and bench press. As for assistance exercises, good mornings, back extensions, hip thrusts, reverse hypers, weighted planks, ab wheel rollouts, side bends, hanging leg raises, board presses, floor presses, chest supported rows, and one arm rows top the charts! Thanks for your comment.

Forces are important but also note all of this is static and muscle recruitment patterns change in relation to the body and the surface it will land on. A single leg hop going up and down will certainly be different going side to side.

Anteroposterior exercises don’t get the same stimulation of below the knee muscle groups (hence the importance of axial loading) since the ankle works vertically.

This is why I don’t think a CHT (Contreras Hip Thrust) can be classified as an activation (load and motor units) or primary lower body lift.

Carlos, I appreciate you posting your thoughts. I am working on a blog that I believe you will appreciate. While I can see your point regarding this issue, I don’t agree with it. I could ramble on for a long time about this but here is one main point to consider. Russian research from many years ago found a strong correlation between the bench press and the shot put. A bench press, as you know, is performed lying down, and doesn’t involve a ton of communication with the ground. However, it does arguably the best job of strengthening the shoulder musculature necessary for shot putting in a specific manner to the shot put. The shot putter still shot puts and receives “on the track sensory stimuli,” but the strength training adds to his shoulder power.

In the same sense, the CHT (Love the name by the way!), although trained supine like the bench press, simply adds glute strength and hip extension power in a specific manner to sprinting and as long as the athlete is sprinting, the additional power/strength will be incorporated/blended into the sprinter’s motor abilities.

Of course, the shot putter and sprinter will still squat, so the best outcome is to have a well-rounded program that includes squatting, hip thrusting, and event-training in the form of sprinting, shot-putting, or whatever event/activity in which the athlete competes. Squats do a great job of strengthening the glutes in a hips-flexed position, while hip thrusts do a great job of strengthening the glutes in a hips-extended position. One without the other is sub-optimal.

Lastly, sprinters do plenty of ground-based training in the form of sprints, plyos, drills, and lower body lifts. There’s certainly room for a lower body lift that is performed with the back on a bench in order to train the horizontal/anteroposterior sprinting vector (especially considering the fact that the hip thrust kicks the shit out of squats in end-range glute activation which is a critical power range in sprinting…ground contact). Thoughts?

Bret,

I will have to think about this. You may be on to something…..I will give you a buzz later. You put a lot of work into this post and I think it should be an article. I responded on facebook Great job.

-C

Bret,

Thought provoking, I enjoy reading your stuff, thanks.

Regarding the hip thrust out performing squats for end-range glute activation; does this enhancing sprinting?

At the terminal hip extension, has not the force already been created and momentum is now taking the hip through this end range?

There just seems to be too much coordinative action going on in stride mechanics for a single joint exercise to do much for enhancement in this skill… ???

Aaron

Aaron, I enjoy reading your blog too and thank you very much for the comment. As for hip thrusting, I emphatically believe it does. I believe that all ranges of hip extension (and hip flexion for that matter) are important in a sprint cycle. I’m not sure if there is any range that is more important than another, but if there is it may very likely be toward neutral in the ground contact ROM.

At any rate, the hip thrust shows more glute activity even in a stretched (hip flexed) position than a squat, however the end range is where the difference is most pronounced. This is based on the results of 4 different individuals (not a huge sample size but I’m still confident); the squat just isn’t that good of a glute exercise (at least when using surface EMG on the various fibers that I’ve tested which are pretty comprehensive – upper, middle, lower, inner, outer) in comparison to the hip thrust or deadlift. It may get you sore but it doesn’t activate a ton of glute (both mean or peak) as measured by surface EMG. Perhaps there would be a difference if fine-wire EMG was used but I’m not so sure it would. I’m working on a blog that will discuss some of this stuff and show EMG printouts and diagrams to illustrate my points. I believe that you’ll enjoy the blog which should be coming next week or the one after that.

However, in the meantime, just think about the following things: When the foot touches down the hip will actually be pulled into flexion for a brief moment as the body overcomes ground force reactions (I have a study that shows this). So the ground-contact phase consists of two phases, overcoming braking forces and then accelerating the thigh rearward into extension. If there exists a weakness in this zone I believe it will be of great detriment to the sprinter. I realize that there has been considerable EMG research on sprinters that depicts the muscle activation through the various phases (and peak glute activation occurs at foot strike according to studies), but I tend to think of it logically; kind of like McGill’s “Superstiffness” concept. What if a puncher or golfer could accelerate quickly but buckled/crumbled upon contact? What if a sprinter could accelerate the thigh quickly but had energy leaks/weakness/poor mechanics/etc. upon ground contact? It would surely negatively impact speed. I believe that this range may be the most important range in sprinting…and the most overlooked/ignored. Thoughts?

Squats are primarily quads no? Deadlifts too, unless you RDL it.

I think one of the benefits of the hip thrust (and really the RDL too) is that it allows the glute to be attacked while taking the quad out of the equation. Not just for isolation, but as a method of working the glutes for people with messed up knees, where squats/LP/DL are not well tolerated.

Bret,

Good point about the bench press and shot putting. Some firmly believe that if you want to throw 20m, you have to be able to bench 200kg. I’m sure there are exceptions, but not many.

Erik Korem wrote a couple of articles discussing the importance of training “hip hyperextension” for EFS. Certainly gets one thinking and, while it won’t be the key to running 10.00, it deserves looking into.

You put out some great info and it’s refreshing that it’s not the same regurgitated Kool-Aid drinking material that’s become all too familiar.

Rich, I read Erik’s articles on the subject a while back on Elitefts, they were good reads. I believe he just proposed sled maneuvers for this purpose, whereas I propose actual strength training exercises to reach the hip hyperextension ROM. Thanks for the comment!

Bret, I’ve been reading your blog for awhile, but this is my first time commenting. I don’t have any questions, but just wanted to tell you that your blog is phenomenal and you continue to produce excellent content (especially this post). Keep up the great work.

Thank you very much Robert! I appreciate the kind words.

Bret,

I’ve been reading a lot your articles and blog posts, and just wanted to thank you for putting great information and content regarding training that is also simple to understand.

You have managed to take a subject like Loaded Vector Training and really simplify it…no easy feat…

I look forward to reading more of your posts.

Thanks Shyam! Much appreciated.

Bret, I need a ruling. A few months back, in your article about hip extensions and reverse hypers, I told you about what my ex-bodybuilder chiropractor had to say about them and asked for your opinion. Well, the same guy is back with an opinion I thought was pretty weird.

“What the hell do you want strong hamstrings for? You have a desk job. Strengthening the hamstrings will make them even more tight. You should focus on strengthening quads instead, which will help keep your hamstrings loose.” (paraphrasing)

I told him that deadlifts pwn leg presses (his favorite compound lower-body lift) for glute activation, and he basically said that RDLs take care of that just fine.

What gives? Desk jockey that I am, am I being dumb in focusing right now on getting my DL numbers up? My knees aren’t huge fans of me when I squat, so I typically trap bar DL instead — should getting my trap bar DL 1RM be my #1 focus now instead?

I should mention that my hamstrings have always been tight, no matter how much I stretch them, and they seem to always get incredibly sore from doing anything that doesn’t involve me staring at a screen.

Any thoughts?

James, like I told you before, bodybuilding-types, chiropractors, and even most MD’s think they know a lot about strength training when they don’t know shit. There are few exceptions such as my friend Dr. Perry, but your guy’s advice bothers me for several reasons.

First, you don’t ever need to justify wanting strong muscles! Many speed researchers feel that the hamstrings are the most critical muscles in top-speed sprinting. Strong hamstrings are extremely functional and having well-developed hammies is very rare. So kudos for wanting to strengthen your hamstrings….and your glutes, quads, and all the other muscles in the body!

Second, a new study just came out that suggests that weight training may be better than stretching for flexibility. Here’s a link to the study:

http://www.webmd.com/fitness-exercise/news/20100604/resistance-training-improves-flexibility-too

This is likely due to the fact that when you do exercises like RDL’s and back extensions you add strength to the end-range positions so your body isn’t afraid to go there. In other words, it may decrease neurological inhibition due to perceptions of instability. So just make sure you strengthen the hammies through their hip extension role and not just through their knee flexion role and you will not lose flexibility!

Third, exercises that strengthen the hammies through hip extension strengthen the entire posterior chain. They can help “reverse” the negative adaptations imposted upon your body from sitting all day at your desk. You don’t want your posture to turn to complete crap or you’ll be screwed, so make sure you continue strengthening the posterior chain.

Forth, most of the world is already quad-dominant. Chances are you are too. Being quad-dominant can alter movement mechanics so you never lift or move with your hamstrings. I see this in lifters who try to stay super upright in the squat while letting their knees jut out way past their toes because they’re afraid to sit back since their posterior chains are weak. So being quad dominant can make your hamstrings tight due to imbalance and the fact that the body will force the hamstrings to be stiff for protective purposes since you might injure them because you have weak hamstrings in relation to your quads.

Fifth, the leg press is not a good glute activator! I wrote about this in my glute eBook. I’ve done the EMG testing! I’m tired of people recommending exercises like leg presses and leg curls for the glutes. These people don’t know what in the hell they are talking about. In a leg press the hips don’t move through a considerable range of motion and stay considerably flexed throughout the movement. In fact, they got my glute activation up to 8% MVC whereas in the same study the hip thrust got my glute activation up to 158%. Here’s a quote from my eBook:

My research indicates that hip thrusts activate 18.6 times (or 1,860%) more glutei maximi activity than the leg press. This is not a typo!

Moreover, RDL’s don’t do that good of a job activating the glutes either. “Standard” form on these involve anteriorly rotating the hips and arching the back which causes you get a great stretch in the hammies but it decreases the glute’s ability to maximally contract. During a recent EMG test RDL’s activated around half the glute muscle as a standard deadlift.

You are not being foolish for desiring a strong deadlift. The trap bar deadlift makes an excellent #1 focus. I bet that you can’t increase your hamstring flexibility for two reasons. First, you’re not relaxing into the stretch. Pavel Tsatsouline wrote an entire book about this concept. Breathing patterns have made a recent resurgeance and we are realizing that you won’t get anywhere unless your breathing patterns are up to par. Learn diaphragmatic breathing and practice long static stretches where you learn to relax the muscles. Yoga is great for this reason. And second, as mentioned above, I bet that your hamstrings are tight due to neurological reasons. Gray Cook has developed many techniques to increase hamstring flexibility. Some involve engaging the abs to reduce tone in the hip flexors to allow for a better hamstring stretch. Here’s a link to a video:

http://fms.riaguy.com/exercises/active_straight_leg_raise_with_core_activation

Bill Hartman wrote an excellent excerpt on short vs. stiff muscles. Your hammies may not be short, but instead stiff due to protective mechanisms invoked by your nervous system. Get to the bottom of this and you’ll be able to increase your hamstring flexibility rather quickly. You could have a typical problem involving tight hip flexors, weak glutes, tight erectors and hammies, and weak abs/obliques, sort of along the lines of Janda’s lower crossed syndrome.

I’m a fan of Mike Boyle’s warm-up methodology which consists of foam rolling, 3-D static stretching, mobility drills, and activation work. Be sure to follow up your warm-ups with strength exercises that put the hammies in a stretch position so you add strength and stability to the new mobility. Best of luck!

Bret,

I guess by now I shouldn’t be surprised to have gotten an absolutely epic reply from you. But that’s your style, and that’s why you’re the man.

I didn’t think I needed an excuse to keep hammering on DLs, but I’m the sort of guy who’s going to question himself without solid logic behind it. This is the kind of ammo that I need to keep me going.

(BTW, I crossed the 400 barrier on my DLs on Saturday for the first time – 415, to be exact. I’m following your and Tony G’s advice to take it to the next level, because I know what got me to 400 isn’t necessarily what will take me to 500. Per you article, my slow-grind lockout was probably a function of relatively weak glutes. We all know what that means…)

What’s especially interesting is your comprehensive answer on my tight damn hamstrings. The “relaxing into the stretch” part, in particular, has the ring of truth to it — guess I need to do my homework on the subject (good thing you cite your sources….on a blog entry, no less). I don’t think the issue has to do with tight hip flexors — I realized years ago that their tightness was seriously hurting my success in the gym, and I’ve made a point of stretching them regularly since then — they feel great now.

Good stuff man. Good stuff. Thanks again for pointing me in the direction (after spinning my wheels for way too damn long)!

James – further to what Bret said, your desk-job-tight-hammies are probably actually tight hip flexors. Stretch them and your hamstrings will probably feel less tight. Then feel free to get them strong. I also think the concept of strong and tight is a myth. It’s often weak and tight.

Good blog Bret. It takes me a while to get a chance to sit down and read them fully. Good stuff.

Brett,

You are insanely brilliant brother. Absolutely love reading your blog!

Quick question that may seem dumb to you but I just can’t figure it out –

Why do you consider pushups to be an anteroposterior load vector? Isn’t the load coming from behind your body towards the floor, i.e. posteroanterior? I can see clearly how bench and cable chest press are anteroposterior, but I’m having a hard time with pushups.

Thanks for your help!

Thanks Yudi! I appreciate the kind words. This is where things get muddy. Your point makes perfect sense. With supine and prone lifts the load vectors flip-flop. For example, a supine bench is anteroposterior but a prone push up is posteroanterior, a supine hip thrust is anteroposterior but a prone reverse hyper is posteroanterior. Yet the body activates the same prime movers to perform the actions (pecs, anterior delts, and tri’s to perform shoulder flexion/horizontal adduction in the case of a bench press or push up and glutes, hamstrings, and adductor magnus to perform hip extension/hip hyperextension in the case of the hip thrust or reverse hyper). I will add to the blog and clarify this point. I didn’t distinguish between these in my model as I like to think of horizontal pressing as anteroposterior and horizontal pulling as posteroanterior and both bent leg and straight leg horizontal hip dominant lifts as anteroposterior, but as you pointed out there exist cases where the vectors flip-flop. Thanks for the post!

*I added this information into the blog under the part about “Room for Improvement.”

Oh man, that is so incredibly interesting! Makes sense now!

I wonder if maybe there is something to the idea of training the same prime movers in the same movement pattern but with different load vectors in order to maximize recruitment.

This whole concept has certainly got me thinking about movement in a whole different light.

Thanks so much for sharing your knowledge so generously!

Very interesting article Bret. Being a vector nut (did a MS in Mechanical Engieering) it was interesting to see vectors next to fitness “stuff”

I know you touched on this a bit, but how do you determine which vector (exercise) to load?

I think this is the key question.

Thanks!

Mike T Nelson PhD(c)

http://www.extremehumanperformance.com

Mike – as far as bodybuilding/physique training, I look at the directions of the fibers. For example, it makes sense that the upper pecs would respond better to incline movements and movements that offer a good stretch. As far as sport-specific training, I look at which directions the athlete moves and consider which proportion of each vector should be trained. I believe that all athletes need to hit all the vectors for balance but sometimes the proportions will be skewed. For example, if my focus was on improving max vertical jump I’d offer more axial loading, whereas if my focus was on improving max agility I’d offer more latermedial loading, and if my goal was max sprinting speed I’d offer more anteroposterior loading. Hope that makes sense!

I totally skimmed it. And I know little on this subject. Just looking at it as an engineer.

1. Get rid of the axial/anterioposterior blend. It’s a waffle. You don’t have other places where you show the in between vectors. It’s really not needed to have a 45 deg vector as it is logically a summation of the two anyhow.

2. Add a vector at the feet (similarly to how you have back and front, you should have top and bottom).

3. Only having one lateral vector is OK, I guess since you have bilateral symmetry in one plane only,

4. the pushups and the bench press are the same in terms of the basic force, in the frame of the refernce of the body, so there is not the contradiction you’re worried about.

———————————

a. I’m not sure what it all accomplishes. Are you looking for something to categorize exercises? load movement? Impacts hitting the body? Just have some cool thing that is yours, but is unclear what the point is?

b. I think you need to show push and pull more. You could do that by just changing signs on some of the vectors. (rather than having extra ones).

(1) So axial positive (compression) would be OHP. axial negative would be pullup.

(2) on the footial vector, calf raise or ant tibialis pull would be a similar couple (or squat/DL would be the opposite of a lying cable leg flexion…granted the motions are more complex, but I’m emphasizing the major motion).

(3) bench and row is obvious.

1. I like the AX/AP blend as it allows for a description of acceleration sprinting, horizontal jumps, and other sport actions. I originally created the primary directional load vectors to describe the most common directions seen in ground-based sports. This allows us to choose strength training exercises that train these vectors specifically. However, your point is well-taken as one could easily argue that other blends should exist if that one is offered.

2. With push ups and bench press, the direction of the load is in fact reversed, but the joint actions are the almost identical (save for scapular protraction). In an open-chain setting the motion will move the load forward, in a closed-chain setting the motion will move the load rearward.

3. Sure, a way to categorize exercises, describe movement, and allow us to choose exercises that may transfer better to sport. You hear coaches use planar terminology when vector terminology is often more appropriate. We can have both, but it allows us to be more descriptive.

4. Love the idea of axial positive vs. axial negative. Great thought! This would certainly cover dorsiflexion and hip flexion too.

5. Great thoughts. I may work the axial positive and axial negative stuff into the blog. Thank you very much for your thoughts.

PolyisTCOandbanned – I’m sure you already know this, but squats are primarily quad but work the glutes well when the hips are flexed considerably. Deadlifts use less quad and more hammy and work the glutes well through a more significant ROM. Although you are correct in that nearly everyone can tolerate properly performed hip thrusts (I’ve never had a client who couldn’t but I could see how an extension-intolerant low back pain client with weak glutes would struggle, for instance), however, surprisingly the quads reach higher levels of activation in a heavy hip thrust than they do in any other exercise (even a squat or lunge). This is due to the intense isometric contraction of the quads while the knee is bent. I wouldn’t say it builds the quads as well as squats or strengthens them through a full ROM like squats, but they do activate a ton of quad. The barbell glute bridge doesn’t activate that much quad in comparison to the hip thrust. Anyway, your point is still well-taken as it is certainly a lift that can be used by individuals who are suffering from certain types of knee and back pain.

Thanks Bret. I agree with that, but the issue becomes when to expand the requirements as specialization has a cost.

Bench press Billy will make great progress benching 5 Xs a week perhaps when he starts, but soon he stalls and starts to LOOK like a bench press.

Put him on a steady diet of no bench press (Billy is sad), and inverted rows and 4 weeks later his bench went up (Billy is happy and hires you again).

The trick is to maximize specialization, but not too much.

Any thoughts?

Rock on

Mike T Nelson PhD(c)

Mike – I’m glad you brought up this point. For years I’ve heard of these “magic tricks” that trainers employed to rapidly boost strength…seated l-flies causing an athlete’s incline press to sky-rocket 100 lbs in 2 months…inverted rows boosting one’s bench press, etc.

I just don’t buy it too much. Of course I agree that the body will limit its capacity to lift heavy if there’s a perception of instability, imbalance, and injury. Of course if Bench Press Billy does nothing but bench he’ll benefit tremendously from strengthening his lats and scapular retractors. However, I don’t feel you have to quit benching (or incline pressing, squatting, etc.) to keep making gains. I feel that you can simply prioritize the other movements and prescribe higher volume for the weaker movement patterns while still performing the other lift.

I think every client I ever trained did a form of squatting, deadlifting, hip thrusting, bench pressing, rowing, overhead pressing, and overhead pulling. I may have started out with bodyweight box squats, light dumbbell bench, etc., but I’ve never omitted any movement patterns.

I would think that you would agree with this line of thinking as we both agree that weight training improves flexibility, mobility, stability, and strength simultaneously so it acts as a strengthening and “corrective” exercise at the same time if there is limited mobility. In other words, let’s say someone has poor t-spine extension…that doesn’t mean I shy away from squats, deadlifts, military press, etc. Improving form on these movements while getting stronger is exactly what they need to improve their mobility (along with thoracic extensions, etc.). Now I’m going off on a tangent.

To get back on topic, if an individual has weak low traps, glutes, etc., I don’t stop pressing or squatting; I simply prioritize (by sequence and volume) rows, chins, deads, hip thrusts, etc. and place less of an emphasis (less volume and later on in the workout) on pressing and squatting until the balance I seek is realized. At this point, I can go back to the drawing board and re-sequence exercises. I believe that this approach allows for greater retention of strength and possibly more strength gains within a fixed time-frame.

Anyway, great thoughts!

“I would think that you would agree with this line of thinking as we both agree that weight training improves flexibility, mobility, stability, and strength simultaneously so it acts as a strengthening and “corrective” exercise at the same time if there is limited mobility. In other words, let’s say someone has poor t-spine extension…that doesn’t mean I shy away from squats, deadlifts, military press, etc. Improving form on these movements while getting stronger is exactly what they need to improve their mobility (along with thoracic extensions, etc.). Now I’m going off on a tangent.”

As I’m reading this, I’m playing the song from 2001 A Space Odyssey in my head!

This statement may mark the beginning of a new dawn…a dawn of less corrective exercise and activation!

Imagine getting all those benefits from lifting weights. What a time saver!

Weight training can definitely get us there on its own, however the best system in my opinion involves doing correctives in the form of active recovery in between sets. This way it doesn’t add any length to your workout. When your movement is ideal, then you no longer have to do correctives as you’ll be moving through those ranges of motion when you lift weights. Of course, there are always situations where individuals have pathology or extensive dysfunction which would prevent them from responding well to the system I just mentioned. But for relatively heatlhy individuals the system I described works just fine.

Rich, I would agree with you.

I don’t do hardly any traditional “corrective work” at all any more.

How much will the body learn from 5 lb weighted YTWLs compared to a heavy squat?

Which one has both the greater potential (due to load and stress) to make the athlete better or worse?

I would go with squat (ditto for deadlifts, bench, etc)

The key is to make sure the exercise makes the athlete better.

This can be done by an active range of motion test. More ROM = better movement. If you want to sub in another test, that is fine too (gait, speed, etc).

So, if ALL exercises we do make an athlete move better, than all exercises are corrective, yes?

If all of them are corrective, then none of them are any different so we can just call them exercise.

The key then is to work with the athlete to find the exercises that allow them to move better.

Rock on

Mike T Nelson PhD(c)

Hey Bret,

Can you please give us the answers to the “application to sport specific training” questions? Just for clarification. Thanks.

• How would a static lunge have an axial vector whereas a walking lunge would have an anteroposterior/axial blend vector? Static lunge moves you up and down, walking lunge has you moving up and forward. Since there is a forward component the glutes are active through more of a ROM.

• What is the difference between a good morning, 45 degree hyper, and back extension? Hardest part of GM is bottom; gets easier as you rise. Hardest part of back extension is the top (easy at the bottom). The positions of maximum contraction are opposite. The 45 degree hyper is a blend between the two.

• How do load vectors impact accentuated regions of force development and positions of maximum muscular contraction? For example, in what position is the most difficult part for the glutes in a squat (axial loaded), at the bottom (hips flexed) or at the top (hips neutral)? In what position is the most difficult part for the glutes in a hip thrust (anteroposterior loaded), at the bottom (hips flexed) or at the top (hips neutral)? What about a good morning and back extension? Hardest part of a squat is the bottom or mid-range, but the top is easy. The hips flexed position gets worked best for the squat. In the case of a hip thrust, the hardest part is up top, where the hips are in a neutral position. This zone corresponds to the zone of ground contact in sprinting

• Which implement would be best for training rotary power; a landmine unit, bands, dumbbells, cables, a barbell, a kettlebell, a trx, etc.? Cables and bands! They let you train more of a pure torsional vector.

• During a side lunge is the emphasis on pushing upward or laterally? Would a slideboard be better at training lateral power? It’s more on pushing upward. A slideboard would definitely be better as the emphasis is on pushing laterally.

• Would a band or dumbbell be more useful for training punching power in terms of a jab? What about an uppercut? For a jab, use bands or cables to mimic the line of pull in a jab or cross. For an uppercut, a dumbbell works very well in resisting the line of pull as the uppercut is axial (and torsional in the hips), whereas the jab or cross is anteroposterior.

• What implement would be better for training for rotary power for chops and lifts, a medball or a cable column? A cable column. With a medball you have much more axial loading and not as much torsional loading.

• For sprinting speed should you use a weighted vest to provide more axial loading or a sled to provide more anteroposterior loading? Well this was studied by researchers and neither was found to be better than just plain sprinting for speed gains, but in theory the sled would be better as horizontal forces are king with speed.

• Ask the same question except now the question applies to resistance training: Should you use a hip thrust or a squat to train for maximum upright sprinting speed? A hip thrust as it works on anteroposterior (horizontal) forces at the hip joint.

Bret:

I honor your knowledge, integration and application of your knowledge. I’m 57, with a BS in Exercise Physiology & Therapeutic Exercise. In addition, since the degree was in 1975, and my ongoing “research, integration & application”, has given me a “PhD in Results”. I’m a “one-of-a-kind” trainer. Specifically, I’ve copyrighted the name “Specialty Exercise & Injury Improvement”(SEIIT). “Specialty Exercise” is specific exercises that simulate the EXACT, individual movements of any event (need) with strength & endurance, while incorporating “S.A.I. D. Principle” (Specific Adaptation to Imposed Demands) with Somatotype & Temperament, to improve overall performance—

“Injury Improvement Specialist”— Through Specialty Exercises, I isolate the injure “angles of the range of motion” and specifically work ONLY the uninjured angles. This expedites healing and improves the “mindset” of the individual.

With that brief overview to me, I’m faced with another physical challenge to heal on my own. Not having the necessary insurance needed for 100% verification of injury, using my knowledge “database”, I’ve deduced it to be a double “partial to full tear” of both origins of the Gluteus Maximus & Piriformis muscles. This is deduced from manual muscle & movement tests, past history of “fall” traumas and well over 100’s of corizone shots in the Rt. SI joint. In addition, due to spinal stenosis and disc degeneration of entire spine, I have nerve impingement from the Sacral plexus (L4-S2)of the Superior & Inferior Gluteal Nerves.

Again, I give you this info to help you give me the answer to my “challenge”, or “where” to find it. Specifically, I need graphs & data showing the directional forces in normal, frontal & rotatioal gaits as shown trough vector analysis. My reason is the following. Using the “construct” of “Injury Improvement”, I NEED TO “SEE” THE DIRECTIONS OF “FORCE” IN ALL INDIVIDUAL MOVEMENTS OF 1) NORMAL FRONTAL WALKING, & 2) SIMPLE “CHANGE OF DIRECTION” FROM NORMAL FRONTAL WALK.

From this, I can accomplish 3 things: 1) isolate movements that keep “irritating and/or increasing” the injury (not allowing it to heal),and in it’s place 2) substitute the “non-injured areas” to take over the ability to WALK! 3)Finally, when proper healing through RISE & Immoblization through Isolation (I/I), has been established, I can design stretching exercises SPECIFIC TO THE INJURY/weakened areas. And then upon completion of that phase, enter in to the “strengthening phase” using SEIIT.

If you have this info on “directional forces for frontal walk and change of direction from it—-visual aids and text, this will be dynamically helpful in “buying me more time”.

Rock

It’s amazing to read all your articles. You are a top reference for all personal and physical trainers. I work in spanish soccer league and i would like to write to you that it is really great to read your web and scientific articles. Thanks!