There are many misconceptions in the strength training and physical therapy communities regarding anterior pelvic tilt (APT). In this article, I will post my current thoughts and beliefs pertaining to APT, specifically concerning the questions listed below. Where possible, I will support my statements with scientific references from the literature.

- What is APT?

- Is APT advantageous from an evolutionary perspective?

- Can we fully trust all research measuring APT?

- Is APT abnormal?

- Does APT lead to low back pain in typical everyday living?

- Can APT lead to back injury in heavy resistance training?

- Do the spine and pelvis actually stay in neutral during heavy or explosive movement?

- Why do ground sport athletes tend to develop APT?

- Why do lifters tend to APT during various resistance training exercises?

- What strategies can be employed to shift APT towards a more neutral alignment?

What is APT?

Possessing anterior pelvic tilt simply means that your pelvis is tilted forward to a greater degree than what is deemed normal. As you’ll see later in the article, there are issues with classifying anterior pelvic tilt. In the video below, Sam Visnic does a great job demonstrating what anterior pelvic tilt is, however, since he created this video in 2011, some of his opinions might have changed since then. I have different data with regards to correlations to back pain and normal degrees of anterior pelvic tilt, which will be explained below in the article. However, the video does a good job of representing the current prevailing thought process that most manual therapist and sports medicine professionals (including licensed massage therapists, physical therapists, osteopathic doctors, occupational therapists, athletic trainers) share in regards to APT, so it’s definitely worth watching.

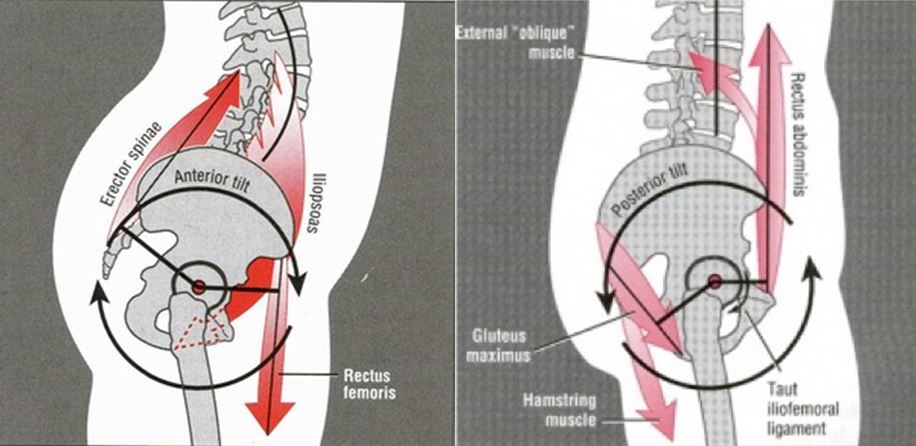

In case you didn’t watch the video, I got you covered. Tilting the pelvis forwards as in the action depicted in the first image below is referred to as anterior pelvic tilting, or anteriorly tilting the pelvis, whereas tilting the pelvis rearward as in the action depicted in the second image below is referred to as posterior pelvic tilting, or posteriorly tilting the pelvis.

Left: Anterior Pelvic Tilt, Right: Posterior Pelvic Tilt (from Neuman 2010)

Stand up and take a moment to move your pelvis into these positions. Notice the different musculature responsible for producing these motions. If you do them correctly, you’ll feel the lumbar erectors and hip flexors tilting the pelvis anteriorly, and you’ll feel the glutes and low abs tilting the pelvis posteriorly.

Interestingly, if you were somehow able to reside inside the acetabulum of the hips, you wouldn’t be able to discern between anterior pelvic tilt and hip flexion, or between posterior pelvic tilt and hip extension. To quote Neuman 2010:

Theoretically, a sufficiently strong and isolated bilateral contraction of any hip flexor muscle will either rotate the femur toward the pelvis, the pelvis (and possibly the trunk) towards the femur, or both actions simultaneously. These kinematics occur within the sagittal plane about a medial-lateral axis of rotation through the femoral heads. Note that the arrowhead representing the line of force of the rectus femoris in FIGURE 1, for example, is directed upward, toward the pelvis. This convention is used throughout this paper and assumes that at the instant of muscle contraction, the pelvis is more physically stabilized than the femur. If the pelvis is inadequately stabilized by other muscles, a sufficiently strong force from the rectus femoris (or any other hip flexor muscle) could rotate or tilt the pelvis anteriorly. In this case, the arrowhead of the rectus femoris would logically be pointed downward toward the relatively fixed femur. The discussion above helps to explain why a person with weakened abdominal muscles may demonstrate, while actively contracting the hip flexors muscles, an undesired and excessive anterior tilting of the pelvis. Normally, moderate to high hip flexion effort is associated with relatively strong activation of the abdominal muscles. This intermuscular cooperation is very apparent while lying supine and performing a straight leg raise movement. The abdominal muscles must generate a potent posterior pelvic tilt of sufficient force to neutralize the strong anterior pelvic tilt potential of the hip flexor muscles. This synergistic activation of the abdominal muscles is demonstrated by the rectus abdominis (FIGURE 2A). The extent to which the abdominal muscles actually neutralize and prevent an anterior pelvic tilt is dependent on the demands of the activity—for example, of lifting 1 or both limbs—and the relative strength of the contributing muscle groups. Rapid flexion of the hip is generally associated with abdominal muscle activation that slightly precedes the activation of the hip flexor muscles. This anticipatory activation has been shown to be most dramatic and consistent in the transverse abdominis, at least in healthy subjects without low back pain. The consistently early activation of the transverse abdominis may reflect a feedforward mechanism intended to stabilize the lumbopelvic region by increasing intra-abdominal pressure and increasing the tension in the thoracolumbar fascia.

Without sufficient stabilization of the pelvis by the abdominal muscles, a strong contraction of the hip flexor muscles may inadvertently tilt the pelvis anteriorly (FIGURE 2B). An excessive anterior tilt of the pelvis typically accentuates the lumbar lordosis. This posture may contribute to low back pain in some individuals.

Although FIGURE 2B highlights the unopposed contraction of 3 of the more recognizable hip flexor muscles, the same principle can be applied to all hip flexor muscles. Any muscle that is capable of flexing the hip from a femoral-on-pelvic perspective has a potential to flex the hip from a pelvic-on-femoral rotation. For this reason, tightness of secondary hip flexors, such as adductor brevis, gracilis, and anterior fibers of the gluteus minimus, would, in theory, contribute to an excessive anterior pelvic tilt and exaggerated lumbar lordosis.

And here’s another quote from Neuman 2010:

With the trunk held relatively stationary, contraction of the hip extensors and abdominal muscles (with the exception of the transverse abdominis) functions as a force-couple to posteriorly tilt the pelvis (FIGURE 4). A posterior tilting motion of the pelvis is actually a short-arc, bilateral (pelvic-on-femoral) hip extension movement. Both right and left acetabula rotate in the sagittal plane, relative to the fixed femoral heads, about a medial-lateral axis of rotation. Assuming the trunk remains upright during this action, the lumbar spine must flex slightly, reducing its natural lordotic posture. While standing, the performance of a full posterior pelvic tilt, theoretically, increases the tension in the hip’s capsular ligaments and hip flexor muscles. These tissues, if tight, can potentially limit the end range of an active posterior pelvic tilt. Contraction of the abdominal muscles (acting as short-arc hip extensors, as depicted in FIGURE 4) can, theoretically, assist other hip extensor muscles in elongating (stretching) a tight hip capsule or hip flexor muscle. For example, strongly coactivating the abdominal and gluteal muscles, while simultaneously performing a traditional passive-stretching maneuver of the hip flexor muscles, may provide an additional stretch to these muscles. One underlying advantage of this therapeutic approach is that it may actively engage and potentially educate the patient about controlling the biomechanics of this region of the body.

Is APT advantageous from an evolutionary perspective?

No, it’s not. In fact, the opposite is true – posterior pelvic tilt (PPT) is advantageous. As we’ve evolved as humans, our lumbar spines have become more lordotic but our pelvises have become more posteriorly tilted to better conserve energy while standing, walking, and running by allowing us to utilize passive elastic energy storage from stretched soft tissue at the front of the hips. To quote Hogervorst et al. 2009:

When a chimpanzee walks upright, the pelvis is more vertical, but the hip maintains about the same position in the pelvis, i.e., is not extended. This is not caused by a lack of possible extension of the hip joint, but by a stiff lumbar spine that lacks lordosis (extension or retroflexion). The chimpanzee walks with flexion of both hips and knees to compensate the forward bent position of the spine that keeps the centre of mass of the upper body forward (ventral) to the sacrum. This “bent-hip, bent-knee gait” brings this centre of mass closer to the point of ground contact of the feet, but at the price of considerable work for hip, knee and back muscles.

When a human walks upright, hips and knees can be in much more extended positions because lumbar lordosis aligns the centre of mass of the upper body with the sacrum and the point of ground contact. Lordosis was made possible when considerable reduction in height of the ilium “freed-up” the lumbar spine, which itself lengthened when the number of lumbar vertebrae increased to five or six. A larger distance developed between lower ribs and iliac crest, creating a waist in the human trunk (as opposed to the barrel shaped ape trunk). The sacrum broadened markedly and tilted forward (horizontally). Changes in the shape and position of the facet joints further increased lumbar spine mobility. Lumbar lordosis thus benefits energy-efficient upright walking. In humans, standing erect requires only 7% more energy than lying down. Dogs use considerably more energy standing than lying, presumably because they have their hind legs flexed.

The downside of this “mobilization” of the lumbar spine may be a relatively insufficient erector spinae muscle. The potential for hypertrophy is likely hampered by the dorsal position of the transverse processes that developed with the “shortback”. Scoliosis and spondylolisthesis are virtually absent in the great apes. Perhaps these spinal malformations in humans are associated with the length and mobility of the lumbar spine and a relative erector spinae muscle insufficiency.

According to Neuman 2010:

Achieving near full extension of the hips has important functional advantages, such as increasing the metabolic efficiency of relaxed stance and walking. Full or nearly full hip extension allows a person’s line of gravity to pass just posterior to the medial-lateral axis of rotation through the femoral heads. Gravity, in this case, can assist with maintaining the extended hip while standing, with little activation from the hip extensor muscles. Because the hip’s capsular ligaments naturally become “wound up” and relatively taut in full extension, an additional element of passive extension torque, albeit relatively small, may further assist with the ease of standing. This biomechanical situation may be beneficial by temporarily reducing the metabolic demands on the muscles but also by reducing the joint reaction forces across the hips due to muscle activation, at least for short periods.

Can We Fully Trust All Research Measuring APT?

No, we cannot. Research data pertaining to anterior pelvic tilt should be interpreted with caution. Due to normal variations in pelvic shape within the human population, it is quite difficult to accurately determine pelvic posture, so all studies examining APT should be interpreted with caution (Preece et al. 2008).

Is APT Abnormal?

No, it’s not. According to a published study by Herrington 2011, 85% of males and 75% of females presented with an anterior pelvic tilt, 6% of males and 7% of females with a posterior pelvic tilt, and 9% of males and 18% of females presented as neutral. Anterior pelvic tilt is also the most common postural adaptation in athletes according to Kritz and Cronin 2008, and it seems to naturally occur with athletes that do a lot of sprinting. Therefore, it’s actually normal for healthy individuals to possess APT, and the average angle of anterior pelvic tilt ranges from 6-18° depending on the study and methods used to determine the angle, with around 12° appearing as the norm (ex: Youdas et al. 1996, Youdas et al. 2000, Christie et al. 1995, Day et al. 1984).

Sprinters tend to have APT

It is therefore normal to have some anterior pelvic tilt, and you shouldn’t be overly concerned about trying to neutralize your pelvic posture, assuming it’s not severe. To put it another way, if you don’t have some APT, you’re not normal.

Does APT Lead to Back Low Back Pain in Typical Everyday Living?

No, it does not. Studies examining the relationship between APT/lumbar hyperlordosis and back pain have consistently shown no or weak links – here are ten of them but I’m sure there are more (Murrie et al. 2003, Schroeder et al. 2013, Nakipoğlu et al. 2008, Ashraf et al. 2014, Nourbakhsh & Arab 2002, Youdas et al. 2000, Tüzün et al. 1999, Mitchell et al. 2008, Christensen & Hartvigsen 2008, Laird et al. 2014). Again, do not be paranoid if you have some APT; it’s normal and it doesn’t increase the risk of developing low back pain compared to those with more neutral pelvic alignments, assuming heavy and explosive loads aren’t placed upon the structures on a regular basis.

There’s a lot more to low back pain (and pain in general) than meets the eye. Posture, structure, and biomechanics only provide part of the picture. For those interested in learning more about pain, please do the following:

- Learn about the biopsychosocial model of pain (as opposed to the postural/structural/biomechanical model)

- Follow Jason Silvernail and listen/read his interviews HERE and HERE

- Look into the work of Lorimer Moseley and other pain experts

- Also follow Greg Lehman (website, Twitter), Todd Hargrove (website, Twitter), Paul Ingraham (website, Twitter), and Adam Meakins (website, Twitter)

Can APT Lead to Back Injury in Heavy Resistance Training?

Yes, it can. However, please understand the difference between exhibiting APT as a posture and anteriorly tilting the pelvis as a movement strategy during heavy resistance training. As eluded to earlier in the article, you should definitely not be worried if you have a little bit of APT posture. There are a hundred thousand athletes practicing or performing right now with APT, and they get by just fine. Believing that APT is dangerous can deliver a Nocebo effect which isn’t good. Slight pelvic tilt is fine, but going too far into APT will usually result in excessive lumbar hyperextension, and going too far into PPT will usually result in excessive lumbar flexion (Levine & Whittle 1996, Day et al. 1984). Hence the term, “lumbopelvic rhythm” – lumbar extension and APT are associated with one another, as are lumbar flexion and PPT. When moving near the end ranges of their postural capabilities, these extreme postures combined with heavy loading can easily lead to injury over time.

Spinal hyperextension under high load can lead to higher incidents of spondylolysis and other injuries to the posterior elements of the spine (Roussoully & Pinheiro-Franco 2011, Alexander 1985). When you lift heavy weights, you usually want to keep your spine and pelvis as neutral as possible. However, there is some wiggle room in that it is possible to slightly tilt the pelvis anteriorly or posteriorly without dramatically affecting lumbar posture (it is my unsubstantiated belief that the sacrum must move with the pelvis which would mostly alter L5-S1 and L4-L5 posture, but L3-L4, L2-L3, and L1-L2 posture could remain relatively unchanged, but this would require study to substantiate the claim), which leads in perfectly to the next section.

Do the Spine and Pelvis Actually Stay in Neutral During Heavy or Explosive Movement?

Your spine and pelvis never really stay in neutral when performing dynamic movement; that’s a misconception. For example, the spine has been shown in the research to move considerably during exercises and activities that are thought to involve a relatively stable lumbopelvic region, including squats, deadlifts, kettlebell swings and snatches, rowing exercises, overhead pressing, good mornings, strongman exercises, sprinting, and jumping:

- Squats (McKean et al. 2010, Walsh et al. 2007, Vanneuville et al. 1992, McKean & Burkett 2012)

- Deadlifts and squat lifts (Cholewicki & McGill 1992, Shellenberg et al. 2013, Mitniski et al. 1998, Granada & Sanford 2000, Potvin et al. 1991, Bazgari et al. 2007, Toussaint et al. 1995, Hwang et al. 2009, Nelson et al. 1995, Tafazzol et al. 2014, Kingma et al. 2010, Bazrgari et al. 2007)

- Kettlebell swings and snatches (McGill & Marshall 2012)

- Rowing exercises (Fenwick et al. 2009)

- Overhead pressing (McKean & Burkett 2014)

- Good mornings (Vigotsky et al. 2015, Schellenberg et al. 2013, McGill et al. 2009)

- Strongman exercises (McGill et al. 2009)

- Running and sprinting (Schache et al. 1999, Schache et al. 2000, Schache et al. 2001, Schache et al. 2002, Seay et al. 2008)

- Jumping (Blache et al. 2013, Blache & Monteil 2014), and

- Various activities of daily living (Bible et al. 2010)

As you can see, the spine and pelvis do indeed move during heavy and explosive movement, indicating that the spine and pelvis are used dynamically to generate torque. In fact, during the deadlift, the spine can be used just like a crowbar by relaxing the lumbar erectors and using the hip extensors to “wind up” the spine against the barbell load until sufficient muscle torque is produced to raise the barbell off the ground, thereby relying on the passive structures such as the iliolumbar ligaments for torque generation. To quote Snijders et al. 2004:

For explanation of the loading mode in slouching we compared the spine with a crowbar, using the iliolumbar ligaments as fulcrum and pivot. This comparison illustrates the kinematics as well as the expected force magnification. Characteristic for the crowbar model is forward flexion of the spine combined with backward tilt of the sacrum relative to the pelvis. This loading mode is maximal when back muscle protection against flexion is absent, e.g. in relaxed slouched sitting. In this respect model calculations resulted in iliolumbar ligament stress near failure load.

Regular use of this lifting strategy would therefore be highly recommended if it weren’t markedly more dangerous, as the spine is not well-suited to handle full flexion of the spine. The spine is indeed designed to move during high load and high power sporting actions, but the motion should be limited to mid-ranges. Moving to end ranges of flexion, extension, lateral flexion, and/or rotation is exponentially dangerous and risky. Therefore, it’s wiser to rely more on the active structures (contracting muscles) than the passive structures (stretched erector spinae, stretched spinal ligaments, etc.) for torque generation under heavy loading. What then is the appropriate spinal and pelvic posture for every situation?

The answer to this question depends on who you ask. Stu McGill, the world’s leading expert in spinal biomechanics in relation to strength training, would tell you that the neutral position is always best for spine safety…both neutral spine and neutral pelvis. However, two legendary sports scientists by the names of Yuri Verkoshansky and Mel Siff (also the authors of Supertraining), felt otherwise. According to them:

The pelvis plays a vital role in the ability of the athlete to produce strength efficiently and safely, because it is the major link between the spinal column and the lower extremities… a neutral pelvic tilt offers the least stressful position for sitting, standing and walking. It is only when a load (or bodymass) is lifted or resisted that other types of pelvic tilt become necessary. Even then, only sufficient tilt is used to prevent excessive spinal flexion or extension… The posterior pelvic tilt is the appropriate pelvic rotation for sit-ups or lifting objects above waist level. Conversely… theanterior pelvic tilt is the correct pelvic rotation for squatting [and] lifting heavy loads off the floor. – Supertraining 2009

I’ve asked Stu McGill for his take on this matter and he defends his stance, saying that neutral spine and neutral pelvis is always best. He and Mel Siff were close friends before Mel passed away, and he believes that Mel would defer to his judgement on this topic since Mel (and Yuri) weren’t spinal biomechanists and didn’t study the topic for a living. My thoughts on this matter waiver, and lately I’m more inclined to agree with Stu. However, based on my experience, individuals with flexion intolerant spines seem to benefit from slight APT at the bottom of squats and deadlifts, and individuals with extension intolerant spines seem to benefit from slight PPT at the top of hip thrusts, back extensions, and deadlifts, indicating that ideal posture depends on the individual.

If you agree with Mel and Yuri and you believe that some slight pelvic tilt can help buttress the spine by creating torque in the necessary direction in order to help stabilize the spine and better prevent buckling, just make sure that the pelvic tilt kept in mid-ranges so it doesn’t dramatically impact spinal posture. In conclusion, either keep the spine and pelvis in neutral to the best of your abilities at all times during exercises that require core stability, or allow for some slight APT with the hips flexed and some slight PPT with the hips extended. Obviously, individual differences in anatomy and injury history must be taken into account when making this decision. Later in this article there will be an embedded video which will shed more light on this topic.

Why do Ground Sport Athletes Tend to Develop APT?

Ground sport athletes generally do a lot of running and sprinting. Kritz & Cronin 2008 state:

The advantages of anterior pelvic tilt and resulting lordotic posture are believed to be an increased hip extension, which allows the running and jumping athlete to apply force over a longer time resulting in a greater impulse.

Although the theory provided by Kritz & Cronin is very plausible, it is important to know that elite sprinters do not use greater hip extension ROM compared to novice sprinters, however, there are still a couple of very good reasons why APT could be markedly beneficial for sprinting speed.

The first reason is that the hip is stronger at hip extension when it’s flexed forward. Worrell et al. 2001 showcased the torque-angle curve for maximal isometric hip extension. Essentially, hip extension is strongest when the hips are fully flexed and weakest when the hips are fully extended.

This relationship has been shown to exist in probably 8 different studies that I’m aware of, and I verified this relationship on myself when I was in New Zealand experimenting on the Human Norm isokinetic dynamometer at AUT University. I assumed that since I could hip thrust 600+ lbs but only squat around 400 lbs at the time that I would possess an altered hip extension torque angle curve – one that was more flat or more even throughout the hip range of motion. But this wasn’t the case. I, along with subjects in all the other studies, possessed approximately 2.5 times more hip extension strength at 90 degrees of hip flexion compared to at 0 degrees of hip flexion (neutral position). Since APT is synonymous with hip flexion, this means that the hip range of motion associated with ground contact during sprinting will be stronger in someone with APT compared to someone with a more neutral pelvic posture.

The second reason is that at mid-stance during ground contact in gait, the hip ligaments that resist hip extension pull taut and reduce hip extension power (Simonsen et al. 2012). In fact, they reverse hip extension torque production to hip flexion production, which doesn’t make a lot of sense being that hip extension torque generates horizontal propulsive force into the ground (Huang et al. 2013) and is critical for faster running speeds (Schache et al. 2011). Horizontal force production is critical for faster running speeds as well (Brughelli et al. 2011, Morin et al. 2011, Morin et al. 2012, Morin et al. 2015). An athlete with more APT, or one that anteriorly tilts his or her pelvis to a greater degree when on the ground, will not run out of hip extension range of motion as quickly as an individual with a more neutral pelvic posture when the foot is in contact with the ground during sprinting, which will prolong the production of hip extension torque and subsequent horizontal propulsive force generation.

These theories need to be substantiated in future studies in order to be considered valid.

In Olympic weightlifting, at the bottom of a snatch lift, APT appears to be a highly important variable for successful lifts (Ho et al. 2007). This is probably due to the tendency to place the lifter in a better position to maximize power output during the 2nd pull phase of the lift. Heel elevation increases APT (Franklin et al. 1995), so it’s a wise strategy to wear heeled shoes when performing Olympic lifts.

Why do Lifters Tend to APT During Various Resistance Training Exercises?

Any good strength coach witnesses dozens of incidents of APT during resistance training on a daily basis. You’ll commonly witness lifters anteriorly tilting their pelvises during glute ham raises, Nordic ham curls, lying leg curls, planks, ab wheel rollouts, push-ups, hip thrusts, glute bridges, back extensions, squats, deadlifts, good mornings, and bent over rows. The reasons why individuals resort to excessive anterior pelvic tilt during heavy resistance training is multifactorial and dependent on the movement in question and will differ depending on whether the APT occurs during a squat, a hip thrust, or an ab wheel rollout. Interrelationships between relying on the spine and pelvis for stability, relying too much on the hamstrings for hip extension, possessing poor gluteus maximus and/or abdominal strength, possessing excessively tight hip flexors and/or lumbar erector spinae, possessing unique individual hip anatomy, and/or possessing faulty motor engrams must be examined.

In case a list helps you, the reasons why athletes resort to APT are due to a combination of:

- Lack of knowledge of sound exercise form

- Poor motor control in the lumbopelvic region

- Insufficient abdominal/oblique strength and stability

- Insufficient gluteal strength and stability

- Insufficient hip extension mobility/tight hip flexors

Here I will provide my opinions and elaborate upon the general reasons why APT occurs during various types of movements.

Knee Flexion Exercises: glute ham raise, Nordic ham curls, lying leg curls

During knee flexion exercises, it is very common for lifters to resort to APT. Let’s assume that the lifter indeed understands proper form and isn’t anteriorly tilting the pelvis just because he or she doesn’t know any better. With this assumption met, lifters APT during knee flexion exercises to provide a muscular advantage. Since the hamstrings shorten during knee flexion, their force production potential is diminished. Knee flexion, hip extension, and posterior pelvic tilt shorten the hamstrings, while knee extension, hip flexion, and anterior pelvic tilt lengthen the hamstrings. By anteriorly tilting the pelvis during knee flexion, the length change is mitigated (the hamstrings don’t shorten as much), thereby allowing for better force production. For these exercises, it is natural for a lifter to resort to APT because it improves exercise performance. However, just because a particular technique allows for better performance, it doesn’t necessarily mean that the technique should be used, since it could lead to suboptimal results in strength and mechanics on the field. Therefore, it is recommended that the lifter focuses on motor control drills for the lumbopelvic region and learns how to keep the pelvis relatively stable during these exercises. Exercise difficulty can be regressed, and eventually the hamstrings will become stronger at shorter muscle lengths, thereby solving the problem.

Anti-Extension Core Stability Exercises: planks, ab wheel rollouts, push-ups

During anti-extension core stability exercises, it is also quite common for lifters to resort to APT. Let’s assume that the lifter indeed understands proper form and isn’t anteriorly tilting the pelvis just because he or she doesn’t know any better. With this assumption met, lifters APT during anti-extension core stability exercises for different reasons compared to knee flexion exercises. In the case of these exercises, the abdominals and obliques simply cannot maintain lumbopelvic stability during the exercise, and therefore they “fail” by entering into an eccentric contraction. Eventually, stability will be reached due to 1) bony approximation of the lumbar spine, which happens when the vertebrae get closer together – this provides passive stability, and 2) stretching of the anterior core muscles, which also provides passive stability. For these exercises, it is natural for a lifter to resort to APT because it improves exercise performance. However, just because a particular technique allows for better performance, it doesn’t necessarily mean that the technique should be used, since it could lead to suboptimal results in strength and mechanics on the field. Therefore, it is recommended that the lifter focuses on motor control drills for the lumbopelvic region and learns how to keep the pelvis relatively stable during these exercises. Exercise difficulty can be regressed, and eventually the abdominals and obliques will become stronger and better able to stabilize the neutral lumbopelvic position, thereby solving the problem.

Anteroposterior Hip Extension Exercises: hip thrusts, glute bridges, back extensions

During anteroposterior hip extension exercises, it is also very common for lifters to resort to APT. Let’s assume that the lifter indeed understands proper form and isn’t anteriorly tilting the pelvis just because he or she doesn’t know any better. With this assumption met, lifters APT during anteroposterior hip extension exercises due to 1) weak glutes, especially at shorter muscle lengths (at end range hip extension), 2) substituting lumbar extension and anterior pelvic tilt for hip extension, which provides an illusion that full hip extension or hip hyperextension is reached, and 3) producing a muscular advantage for the hamstrings musculature – by anteriorly tilting the pelvis during hip extension, the length change is mitigated (the hamstrings don’t shorten as much), thereby allowing for better force production. For these exercises, it is natural for a lifter to resort to APT because it improves exercise performance. However, just because a particular technique allows for better performance, it doesn’t necessarily mean that the technique should be used, since it could lead to suboptimal results in strength and mechanics on the field. Therefore, it is recommended that the lifter focuses on motor control drills for the lumbopelvic region and learns how to keep the pelvis relatively stable during these exercises. Hip flexor stretches for the psoas and rectus femoris can be employed if they are limiting hip extension mobility. The arc of motion during these exercises should stop once the hips run out of extension and reach the limits of its mobility. Exercise difficulty can be regressed, and eventually the gluteus maximus will become stronger at shorter muscle lengths, thereby solving the problem.

Axial Hip Extension Exercises: squats, deadlifts, good mornings

During axial hip extension exercises, it is also very common for lifters to resort to APT. Let’s assume that the lifter indeed understands proper form and isn’t anteriorly tilting the pelvis just because he or she doesn’t know any better. This is important to consider because many individuals have been taught to APT considerably during these movements, since this has been the prevailing cue over the past decade – think “chest up,” which emphasizes thoracic extension but will often bring the lumbar spine and pelvis into extension along with it. I still use this cue all the time with my clients, but “ribs down” has become popular too in the past couple of years, which emphasizes stabilization of the lumbar spine and is to be used with individuals that are prone to excessive spinal hyperextension during axial lifts. At any rate, assuming that individuals are aware of proper technique, lifters APT during axial hip extension exercises due to 1) producing a muscular advantage for the hamstrings musculature – by anteriorly tilting the pelvis during hip extension, the length change is mitigated (the hamstrings don’t shorten as much), thereby allowing for better force production, 2) substituting lumbar extension and anterior pelvic tilt for hip extension, which provides an illusion that full hip extension is reached, and 3) weak glutes (mostly in the case of the deadlift), especially at shorter muscle lengths (at end range hip extension), and 4) better passive force production at the bottom of the lifts – APT will lead to a greater stretch in the glutes, hams, and adductors, which increases muscle force production via elastic recoil. For these exercises, it is natural for a lifter to resort to APT because it improves exercise performance. However, just because a particular technique allows for better performance, it doesn’t necessarily mean that the technique should be used, since it could lead to suboptimal results in strength and mechanics on the field. Therefore, it is recommended that the lifter focuses on motor control drills for the lumbopelvic region and learns how to keep the pelvis relatively stable during these exercises. Exercise difficulty can be regressed, and eventually the responsible muscles for carrying out these exercises will become stronger at the appropriate muscle lengths, thereby solving the problem.

What Strategies can be Employed to Shift APT Towards a More Neutral Alignment?

The vast majority of people don’t need to stress about their pelvic posture; they’re within the normal range and they aren’t in danger of experiencing injury. However, certain individuals will benefit from actively attempting to shift their postures towards a more neutral alignment, or at least from improving their motor control and stabilization strategies during exercise. Most manual therapists will recommend manual therapy such as massage or self-myofasical release (SMR) along with static stretching in order to improve APT postures. These methods can certainly help, but they pale in comparison to proper strength training in terms of efficacy in altering posture. So definitely do your stretches, but make sure you strengthen the proper muscles, especially at their respective suggested muscle lengths. It is recommended that the following strategies be employed for improving APT:

- SMR for the rectus femoris, adductors, and erector spinae

- Static stretching for the psoas, rectus femoris, adductors, and lumbar erector spinae

- Strengthening the abdominals and obliques, especially via posterior pelvic tilt

- Strengthening the glutes, especially via posterior pelvic tilt and at end-range hip extension

- Being mindful of using APT postures throughout the day and also during resistance training

Case studies by Yoo 2014 and Yoo 2013 have shown that strengthening opposing lumbar and pelvic force couples will lead to marked changes in lumbopelvic posture. Strengthening the abdominals and glutes will cause APT to move to a more neutral position, and strengthening lumbar erectors and hip flexors will cause posterior pelvic tilt (PPT) to move to a more neutral position. It’s important to note that studies such as Walker et al. 1987 have shown that those with APT are not weaker in the abs and studies such as Heino et al. 1990 have shown that those with APT do not have less hip extension ROM, but to alter pelvic posture, you’re probably going to need to get even stronger at shorter muscle lengths and longer hip flexors and erectors, in addition to modifying daily postural habits. Stretching is also important. Below is a video that shows various ways of improving hip extension mobility through hip flexor stretching, with special techniques such as tilting the pelvis posteriorly to increase the effectiveness of the hip flexor stretch.

It is vital to possess powerful hip muscles to dynamically propel the body as well as strong lumbopelvic muscles to stabilize the core. But strong muscles isn’t enough. You also need plenty of technical practice to ingrain proper movement patterns. Here’s a good video to watch pertaining to the lumbopelvic hip complex during squats, deadlifts, hip thrusts, and back extensions.

As I stated above, even though possessing anterior pelvic tilt is normal and you shouldn’t be overly concerned about it, some individuals with excessive and painful APT should strive to better neutralize their pelvic postures. Moreover, individuals that utilize excessive anterior pelvic tilting strategies while resistance training will want to learn how to better control the pelvis. In my opinion, the best way to combat APT is by focusing on increasing posterior pelvic tilt strength via the following abdominal and glute exercises: American hip thrusts, back extensions with a rounded upper back, glute bridges with a flattened lumbar spine, RKC planks, and hollow body holds. The videos below will be useful:

Conclusion

APT does not provide a muscular advantage during walking, but it does during sprinting and Olympic lifting. More individuals have APT than PPT or neutral pelvises, indicating that it’s normal to exhibit some APT. APT does not lead to low back pain in everyday living but it can lead to low back injury during sports or resistance training if excessive and not kept in check. The spine and pelvis move during heavy and explosive movement, indicating that they are used dynamically to generate torque, however, their motions should be kept in midranges; end ranges of spinal and pelvic motion are risky and dangerous under high loads. The reasons why athletes and lifters rely on APT during sports and exercise depends on the motion and exercise in question and is multifactorial. Resistance training, motor control training, static and dynamic stretching, and manual therapy should all be used to augment pelvic posture or pelvic mechanics during exercise if it is deemed safer or more advantageous.

As I learn more over time, I will update this page and keep it current.

Recommended Reading

Why do I Anterior Pelvic Tilt?

Courageous Conversations With Coaches: Anterior Pelvic Tilt With Elsbeth Vaino

A Better Way to Teach Barbell Glute Bridges and Back Extensions

Weightroom Solutions: The Hyperextension-Prone Lifter

Anterior Pelvic Tilt and Lumbosacral Pain as it Relates to the Hip Thrust and Glute Bridge

Bret that was a fantastic breakdown of a complicated and continuous subject.

I learned a ton.

Thank you thank you

Best

Rocky Steele

Bret my name is Eric Serrano love your article but would like to bring or discuss some points with you

Please don’t share my email.

Eric Serrano

“More individuals have APT than PPT or neutral pelvises, indicating that it’s normal to exhibit some APT. ”

Replace that statement with this:

“More individuals are overweight than not overweight, indicating that it’s normal to have excess bodyfat.”

The problem here is you assume normal means good.

I see your point, but I don’t agree. I don’t think people are supposed to have perfectly neutral pelvises.

To add more confusion to the definition of “normal,” ethnicity has a lot to do with differences in anatomy. Calling APT abnormal or unhealthy is a diagnosis I hear from a lot of white people (particularly white yoga instructors). I’m Italian and like all of my African-American friends, we have natural APT. I have strong abdominals and if you look at the front of my body my pelvis is perfectly aligned, a straight line all the way down. But from the posterior view, there’s a “sway” in my lumbar spine. This is the “neutral” or “natural” anatomy of many groups of different ancestries. We also tend to have more leg and glute musculature. I wish the fitness and medical community would start including more diversity in their studies instead of diagnosing differences as needing to be fixed. I can’t change the curvature of my spine but it’s not scoliosis. I do need to adapt many exercises against conventional wisdom (conventional being the operative word) because they can cause my body-type serious injury.

Hi Bret! Thanks for the article. There’s still something I’m confused about and would love to know your about it if you have the time. Sorry if this a noob question.

How does anterior pelvic tilt relate to knock-knees? I’ve read that APT leads to hip internal rotation which causes knocked knees. But if this were the case, wouldn’t sprinters and ground sport athletes have horrible knee pain and knocked knees since they tend to have APT? Is it that only extreme cases of APT leads to knocked knees or am I missing something?

Great read! Thanks for taking the time to write this up.

Thanks for putting such a well-researched and argued article on the subject out there. I’m also immensely grateful for placing links to precisely the right exercise videos in the article.

I would like to reduce my (life-long) APT somewhat for better long-distance running economy as well as for aesthetic reasons, even though I don’t experience any pain that I can connect to it. Hopefully this gives me the tools to finally do that.

I’m trying to find out where this comes from: ” It is recommended that the following strategies be employed for improving APT:” and then you list them

Do you have a reference for this? I’ve scoured the web and everybody says this but I can’t find a source.

Thanks,

Sam

Btett, congrats on making the article so the year on the PTDC. I learnt so much from reading this article, even though some of it flew over the top of my head. Rarely does the body work in isolation, so APT can affect other parts of the body?

Most people I see with APT, have a flared rib cage which can effect proper breathing mechanics. But i suppose it’s a matter of degrees. Your thoughts?

I see a lot of people with APT rely a little more on spinal extension when going overhead. Only my observation of course. I imagine that can lead to low back pain, over time.

Great work overall Brett, I enjoyed it,

I have apt & it is very painful, I cant seem to get any relief, I had a pulled ligament for 8 years before a pt found it, he said he also fell off a roof so he knew the sytems, I could barely walk or put pressure on my leg, I only have it on my left side, my right is pretty normal & doesn’t hurt at all, except in my lower back a little, but not in the hip or groin area, is there any excercises I can do with a stretch or resistance band for anterior tilt? Thank You

If I’m trying to get this corrected for baseball should I not do any sprints while I’m working on getting my glutes stronger to correct the posture?

this horrible pain is on my left side in the groin area, in the crack of my leg & pelvis, its feels like i got stabbed with a stake or cro bar & its still in there, hurts so bad, I was diagnosed with apt, the only thing that seems to help just a little is the lunge with leg against wall & that hurts so bad to do that, are there any other excercises or stretches I can do with the stretch or resistance bands, I went to the site you gave me & I went to the site you gave & have tried those, I have done a couple excercises with the resistance band but want to make sure im doing the right ones? Thank you..

Getting a lacrosse ball and release the deep hip flexor ls and abs help a lot for some clients of mine look up Kelly starerte he has a good video on it

lol oops, I see I repeated myself a couple times, I had to leave for a min & was in a hurry, so anyways if anyone can give or give me any advice on stretches for this it would be gratefully appreciated, its a deep aching pain 24 hrs a day & its right a the top of my leg on the inside of that bone or ligament, think its a hard piece of ligament or cartlidge, feels like its on the side of that, thanks again

Like most, you seem to take it as given that APT and lumbar lordosis are physiologically inseperable. However, it is possible to have large APT simultaneously with minimal curvature of lower and upper spine. Esther Gokhale’ s”8 steps to a pain-free back” marshalls extensive evidence from, history and present non-western cultures, that the configuration just described is biologically normal and optimal. Westerners in general have excessive S-bends and deficient APT. The S1-L1 disk is actually wedged shaped, and alone in this regard, to support the proper alignment. Modern Western slumped sitting messes with that fundament from childhood, radically stiffening S1-L1 in an excessively flat position, hence producing correlation of APT with lumbar lordosis (not to mention promotion of sciatica and herniation by overly compressing the wide edge of that disk).

I meant S1-L5 of course.

Hold on a minute. Do athletes display APT because they weight train and not because they are naturally predisposed to it? Is APT the result of muscle imbalance due to heavy and or poorly constructed weight training? IE Too much emphasis on heavy squats.

All I know is that I had APT for years and it did cause tremendous back pain. I had a year out from weight training due to illness which also resulted in a lot of muscular atrophy. I no longer suffer with the back pain. I use to sprint, and do multi event, so had a very well rounded training routine, but my coach did have me squat a lot and heavy(270kg). I feel that this may have been the contributing cause to my APT and constant back pain. I had no issues squatting. Never had an injury from doing things in the gym. But honestly, I couldn’t lie down on my back without being in pain or stand for more than a few minutes.

So does APT not lead to low back pain in every day living? Well, before I started weight training I never had an issue. Do I have an issue when in the gym? No. quite the opposite. Because I’ve had issues with my back, I was very conscious of form and have never hurt my self in the gym.

I’m with Blake, I think the conclusions you have drawn are flawed.