The Overhead Shoulder Rotation Quandary

by Derrick Blanton

One thing I noticed very early on in my training journey is that people move and lift stuff differently. Even the top lifters in the world rarely do it exactly the same way. I find myself constantly making mental notes on different lifting strategies.

As you might imagine, I also spend a ton of time studying the coaching techniques, rationales, and cues of the most prominent names in S&C; and then trying to tie it all together with my “in the trenches” observations and firsthand experiences.

Every now and again, I see a disconnect between the “right way” to do a lift, and effective “real world” expressions of loaded movement. Of course, then I obsessively go about trying to figure out the root of the discrepancy!

Take the shoulder, and what constitutes the safest, most congruent position as it arises overhead.

Don’t worry, we are not going to dive back into the scapular “shoulder packing” debate; enough already with that one. Rather, let’s discuss this concept of rotation at the shoulder, specifically external rotation. (FWIW, external rotation when initiated at the proximal shoulder does indeed have a close relationship with ‘shoulder packing’, as externally rotating the shoulder also fires the lower traps pretty hard as a stabilizer. But let’s stay on point here!)

Neutral

Internal rotation

External rotation

The Evolution of “Torque”

MobilityWOD savant Kelly Starrett is probably the most current and well-known proponent of externally rotating the shoulder to provide maximum overhead stability. As a best selling author, and de-facto leader of Crossfit movement principles, KS is one of the most influential movement teachers in the business.

Note that this external rotation technique is not a small detail riding the outskirts of the MWOD curriculum, but rather an overriding motor learning philosophy for the shoulder (and hip) joint: “creating maximal torque through the system”. This includes being able to rotate the wrists internally, while dissociating up the chain and keeping the shoulder in external rotation.

And long before there was a “Supple Leopard”, there was an “Evil Russian”, a brilliant technician by the name of Pavel Tsatsouline, who championed a similar concept in the form of “corkscrewing” the shoulder. And yes, even before Pavel, you may have heard your local meathead at the fitness center telling you to “break the bar”, “show your armpits”… you get the idea.

So without question, this is an idea that has substantial weight behind it. Pardon the pun.

Here comes that pesky real world disconnect, though, and it’s actually a little reminiscent of the prescribed “toes forward” SQ technique, (also intended to maximize ‘torque’): look around and you will see plenty of strong, well trained lifters, even elite strength athletes, not only not doing this…but in fact, often doing the exact opposite.

Granted, this gets tricky to discuss; complicating matters is whether you are using a straight bar to ‘torque’ off of, or dumbbells or rings which allow the shoulder and arm to rotate freely. Let’s give it a try, though, considering first, overhead down.

Pulling Down from Overhead

Most lifters, beginner to advanced, when performing a pull up or pull down that allows for natural freedom of motion at the wrist, elbow, and shoulder (rings, TRX, or Free Motion pulldown, etc.), will naturally adopt this rotational strategy: Internally rotate up, externally rotate down.

Here is my go-to guy for excellent form, Steven Trolio:

In other words, they start pronated ‘pull up’, and finish ‘neutral hammer grip’, or even further into a fully supinated ‘chin up’ position.

Sure, go ahead and test yourself right now.

Elbow moves from pointing out to pointing down. Thumb moves to the outside. External Rotation

Now watch the same lifter this time on a fixed bar, and they will basically try to approximate the same action, torquing off the bar, screwing the shoulder in the socket on the way down, elbows turning to face forwards. So far, so good!

(Less frequently, you will see the bodybuilder with the elbows pointed outwards, flared wide, staying in internal rotation, and performing pure adduction, rather than extension. For some reason, this guy usually has some kind of massive, hellacious back. But I digress.)

Many will point to the fixed bar forcing internal rotation as a shoulder risk, and advocate using the rings, to “let the shoulder move naturally”, i.e. supinate, or externally rotate.

Here’s the thorny question: When they are on the rings and allowed to move naturally, why then do they “re-internally rotate” on the way back overhead, into the “broken” position?

It’s internally rotate up, externally rotate down. This pattern recurs with many a lifter, both pressing and in this case, pulling.

Maybe this technique lines up the lats into a stronger extension pattern. If so, why not just stay in pure extension ‘neutral’ the whole time?

Maybe they want to use more bicep to help as the lat runs out of steam. Sure, but again, why not go back to the top in neutral, at least? Why go all the way into internal rotation as you reach the top position? You don’t have to. You’re on the rings, remember.

It seems that as the humerus elevates, it “wants” to simultaneously internally rotate, even when it doesn’t have to due to a fixed bar. With 360-degrees of motion, many just naturally allow the shoulder to unwind back on the negative into the overhead position of pronation, and thus internal rotation.

Again, are they “broken”?

Pushing Upwards from Down Below

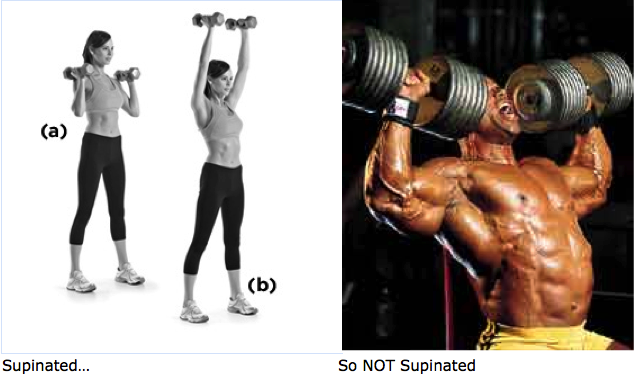

Let’s reverse the action. Have you ever heard of the Arnold Press? It’s a modified shoulder press named after, ah heck, you know who it’s named after! Let’s see it in action:

We see that the Arnold Press starts with an externally rotated shoulder which again spirals medially in the capsule (internally); this time as the press heads to lockout. Same pattern as above, whether we are pressing or pulling, it’s externally rotate down, internally rotate up.

This is contradictory!

But hey, what the heck does Arnold know, silly bodybuilders, right? Their goals are muscle building, not joint safety, per se.

Except I don’t know about you, but when I do the Arnold Press, it feels like an incredibly safe, natural, and congruent movement.

How about just a regular, good old fashioned dumbbell press? Here’s Ben Bruno, one of the hardest training guys I’ve ever seen. Also a pretty prolific author, coach, and exercise inventor. Bruno is battle tested, and innovative. How does he go about pressing a pair of dumbbells overhead?

There it is, that same pattern again! The shoulder rolls to the inside as the press locks out, and reverses on the way down. And not to belabor the point, but once again this is within the context of a free motion, dumbbell movement. Any style of rotation is possible.

So why is he doing it this way?

The further you dive into this murky swamp, the more perplexing it gets. Let’s move on to the barbell where the grip is fixed. Olympic weightlifters go overhead all the time; it’s in their bylaws! A cursory search finds both XR and IR rotational techniques coached and performed.

The Chinese weightlifting team is currently the dominant force in the sport. These guys probably pack their shoulder blades down nice and hard, and externally rotate their humeri, and….uh…hmmm…

Internal rotation!(Thanks to “All Things Gym” for some screen grab insights as to the Chinese overhead position coaching.)

What say you, 2005 world champion Dmitry Klokov? “Show the armpits”? Or try to make the “elbows face back”?

We now officially have ourselves a legit conundrum here.

Fred and George

Finally, meet Fred Koch and his skeleton, “George”. In this video, Fred and George suggest that internal rotation provides for a stable shoulder as the arm rises. Pay special attention to 1:10 – 1:55, and watch what happens to George’s humeral head. It internally rotates.

Thank you Fred and George!

Me personally? I like the XR-up technique when I am doing an aggressive pec minor stretch, or pullover exercise. But when I press a barbell overhead, or do OHSQs, the internal rotation feels so much better as to make it a non-issue.

Trying to supinate my shoulder while driving a heavy barbell up feels like it is going to tear my infraspinatus off the bone. It also seems to force the elbow in front of the bar, compromising its direct leverage. With the elbows not aligned directly under the bar, the lift morphs into a supra-maximal standing “skull crusher” tricep exercise.

On the other hand, when I cooperate with my body, roll the shoulder internally, the elbows end up right under the bar opposing gravity directly. As a nice side effect, the OHPR turns into a fantastic lateral delt move, as internally rotating the shoulder exposing the ‘cap’ to the load. However, this is not a “muscle targeting” technique. This is a “my body wants to do it this way” technique, and my body usually wins these arguments!

To be clear, I can certainly see how others might have different shoulders and different experiences. I also see how a supination moment as part of a larger rotator cuff tug of war might better help keep the shoulder wedged in the capsule.

But this is different than an actual elbow turning, supinating action, that if you somehow don’t achieve, then you’ve allegedly compromised the efficacy of the kinetic chain!

So is this a corrective solve, a blanket prescription on how to raise the arms under load, or a try it and see how it feels kind of deal?

At any rate, forcing square pegs into round holes to match theory is probably not going to end well.

The best that I can make sense of this disconnect between theory and sometime practice is that the shoulder complex, much like the hip complex, may turn out to be more individually “complex” than previously thought.

Scientific and anecdotal feedback, please.

Yes Brett I think your intuitions on this are correct. the way I see it as the arm raises overhead a significant amount of capsular slack is being taken up if you add an external rotation force while raising overhead this seems to double the stabilizing effect o which makes it very hard for the shoulders to reach a fully vertical, locked out position. If this is coupled with restriction in the t-spine or shoulder, it’ll make pressing weights overhead in this way almost impossible. This forces you to fight the weight and your natural or (possibly additional) internal tension. I think Kelly’s thought on this is if you can externally rotate overhead you have proved you don’t have any extra stiffness holding you back and all you get it a stable shoulder. Plus the degree of internal rotation is usually not close to maximal which might be what we all don’t want. Will write more soon.

Capsular and muscular slack*

However Mid range pressing can be locked in with external rotation with no issue. The shoulder really belongs in some degree of IR for any position except midrange (I think of jumping and diving positions for examples of IR in extension). However It seems that the first “half” of the press when the bar is below the head can managed without flaring the elbows (IR) as many old school texts on the Olympic press say not to flare the elbow at the start but at lockout. Some close grips make elbow flare a neccissity as it relates to getting solid leverage. Also Pavel has said in Enter The KB that the KB press was just like the Arnold press. Meanwhile the external rotation “moment” is interesting as it may help prevent a fully internally rotated position which I’m personally not crazy about.

Hi Derrick,

It’s great to see an article discussing joint motion and questioning conventional wisdom!

This is a good (old) paper that you might like, on the effect of ligamentous tension on the humerus during flexion. It turns out it is the ligament that is causing internal rotation of the humeral head:

http://physther.net/content/66/1/55.full.pdf

Full external rotation, with abduction or flexion above 60-90º is the closed-packed position for the gleno-humeral joint – which means once there, your joint is more congruent, which may provide passive stability, however that depends on the direction of force.

Depending on your joint structure, and other passive tissues such as your ligaments, you might not even be able to get into an externally rotated position while your humerus is at 180º – because of the passive structures..

Steven Trolio who is performing the kneeling cable pulldown, seems to be maintaining a similar degree of relative rotation through the abduction/adduction motion, but internally and externally rotating through the radio-ulnar joint. But that may be my eyes that cannot see the shoulder motion!

I was confused by the initial video, open- and closed-torque systems. Isn’t the added restraint (of a bar over dumbbells) simply offering an opportunity for other muscles to contribute due to the added lines of force (such as those offered from reaction forces to rotation on the bar, or friction from the bar is he is pushing in or out)? What am I missing? Or is this just be a translation issue, or that it’s late here in the UK 🙂

Cheers,

Michael

Michael, thanks for the knowledge. Good thoughts!

I may be getting this wrong, but effectively then IR force of the ligament that you refer to is pulling the shoulder away from congruence as it rises to 180. (from the close packed 90-degree XR position)? Or is IR the most congruent position at 180. I will read the paper!

Should we naturally move in the most congruent fashion? And if we do already move like that within our own anatomy, do we need to purposefully deviate for more stability? Yes, these are the questions that keep me awake at night!

I think the bottom line is that end range flexion requires IR in order to move through the capsular and muscular tension associated with that position.

Something similar is happening with the hip during the first couple of pushes in the sprint start. The feet is usually turned outward (externally) and this according to some coaches can reduce the stride length for an inch or two.

Unfortunately this is just how the body works. It is related to “Muscles facilitates other muscles by loading them eccentrically” ‘law’ by Frans Bosch (check his book: http://amzn.to/UreABV).

I have tried to explain it in this blog post: http://complementarytraining.net/the-function-of-muscles-in-the-human-body/

I guess that in the pull-down example you gave, by externally rotating the humerus on the way down we ‘stretch’ the lats and slow down the velocity of their contraction, and this in turn, according to F-V relationship allows more force generation. Same thing with the glutes in the sprint start example.

Regarding the press-up, I am not sure. Maybe something similar is happening to triceps, where internal rotation causes slower contraction of triceps (or delt) and hence allow more force generation. Just guessing….

This again is related to ‘maximizing’ force. Maybe there are other factors involves, like stability of the joint, etc.

More practically, I wonder how much cueing our body actually needs? Over-coaching?

Mladen, it’s an honor. Going to check out your article. Thanks so much.

Also I am going to print out your last two sentences and make T-shirts, ha ha! It gets bewildering sometimes.

I wish anatomists would use something like Euler angles to describe angular orientation. To me, at least, that would be more precise. I find flexion and abduction confusing when they are both needed to describe some motion.

IR/ER refers to rotation of the humerus about the long axis of the humerus, true? So if the wrist stays above the elbow, as in the Arnold press, the humerus does NOT rotate. The humerus does horizontally abduct (either by itself when the press is done “wrongly”, or while flexing, when done right) into the scapular plane. But as far as I can tell, certainly with all the dumbbell presses, there is no rotation of the humerus about its long axis. Or am I missing something here?

That said, there is certainly a difference between angle, motion, and torque. Of course, *net* torque on the humerus will cause it to rotate (which could be flexion, abduction, or ER/IR) depending on the direction of torque. However, as the humerus moves, even if it does not ER or IR, the contribution of different muscles to the torque may change. Perhaps the pecs or lats or delts add torque in the IR direction, so maybe the rotator cuff compensates with addtional torque in ER. Or maybe certain motions changes the torque due to the ligaments.

So having net zero torque could result from no muscle or ligament force, or could result from significant but opposite torques from various actors. My understanding of Starrett’s “create torque” dictum is that we get more stability from the latter than the former. And he prefers, when the humerus is in flexion, that we use muscles to create ER torque, and balance that with IR torque from the joint capsule. Which is a different statement than “best to put the humerus in ER”. One statement is about torque (regardless of angle), and the other about angle (regardless of torque).

I enjoyed reading your comment. If the forearm is not vertical while doing a barbell press I would say that a true internal rotation taking place and that by “creating external rotation torque) we resist that separation. But you do have a great point, which makes me rethink my terminology on the last comment about how it’s not really IR but horizontal abduction that we are talking about in the Arnold press. And I really liked that you said that flexion+abducion is what the press really is, not one or the other, which is why it may feel contrived to try to making pressing one or the other. I definitely would say that actually IR while pressing is not what we are after for the sake of the G/H joint as well as the impact it has on the elbow, scapule, neck etc. I do think that IR and biasing horizontal abduction can solve some leverage disadvantages on both the bench and the press and it seems to show up more with very heavy weights but I see it as a “plan B” strategy when the primary strategy isn’t getting the bar moving.

Bob and Tyler, great discussion, thanks!

This starts out like a math problem that is basic and easy, and then turns out to be advanced calculus!

Bob, your last paragraph is how I read it as well, creating an isometric torque. But it gets tricky when we consider moment vs. action. The best that I could come up with to integrate the idea was to “set it, and forget it”. Set the torque, and then just lift. I frankly realized that I don’t understand the intention of the technique, EXACTLY how to apply it, the underlying rationale; and if it’s something to even worry about in the absence of pain.

On the wrist/elbow alignment part of the equation: If you lock out the elbow with arms in any position, overhead, straight out in front, down to the sides, in any plane etc. you can turn the shoulder internally and then externally like a giant screw with your rotator cuff the screwdriver, effectively “twirling” the fist and never yet never lose the wrist/elbow alignment. You are most certainly rotating the shoulder, yes, and the locked and aligned elbow/wrist are coming along for the ride.

(I actually like to do this to “scrub the shoulder capsule” sometimes.)

The bottom Arnold Press position is the top of a bicep curl, an exercise that is performed in constant, braced shoulder XR. (This shoulder setup is separate from the supination of the elbow caused by the bicep. Thus a bicep curl is supination on top of supination…Head explodes.)

The opposite start position would seem to be that of the dumbbell OHPR as demo’d by the bodybuilder with flared elbows. Now here’s where I go off the tracks: It’s also similar to the position of the top of a Cuban press, the external rotation position coming from an upright row type internal rotation!

Confused!

But the madness doesn’t stop; there!

Note the difference if the elbow is bent and moving in space, as opposed to being fixed as in an arm wrestling contest, or a direct rotator cuff exercise. To IR the shoulder with a bent arm in space requires a “flaring” of the elbows, which is also necessarily shoulder abduction.

Overlap of the two actions, yes?

So when you throw in the position of a flexed elbow in space, it has nowhere to go but out if you turn the humerus internally inside the socket. The elbow, then must move as though you are winning an arm wrestling contest, and with your arm not wedged to a table, this means flaring.

In this sense a bodybuilding lateral delt raise also seems like an internal rotation, and when people say, “control the IR on a bench press” for example, they basically mean, “don’t flare the elbows” too wide.

At the top of the Arnold press, it seems to me that the humeral head has moved into internal rotation. It does not look like the picture of Starrett with the arm overhead and wound up, “showing the armpit” to the front. Rather it looks like showing the armpit to someone off slightly to the side, like a lateral raise performed vertically almost.

Believe me, I have been racking my brain trying to sort out the various abduction and adduction elements, etc. and how they interact with rotation.

Ultimately though, how does any of this translate EXACTLY into lifting technique. Roughly speaking then, does external rotation essentially mean “tuck the elbows” and internally rotate mean “flare the elbows”?

First point: nomenclature. What does it mean to “be in ER”? Compare 2 motions that get you to the same place. Start with elbow extended, arm straight down (0 flex, 0 abduction) and thumb pointed forward. First, flex 90 without any humeral rotation. Arm is pointed forward, thumb up. Compare that with: abduct 90 without humeral rotation (now thumb is forward) and then horizontally adduct 90 without humeral rotation. In this second case, arm is forward just like the first case. However, the first case has thumb up, whereas the second case has thumb left. Yet there was NO humeral rotation during either first or second case. (Pardon the geeky reference, but this reminds me of Killing vectors from general relativity class. The mathematics of rotation has, um, my mind spinning.)

My point is, we (or at least I) do not have a clean definition of what it means to “be in humeral rotation”. I understand humeral rotational *motion* when the flexion/abduction angle is fixed. What I don’t understand is the defintion of *being* in ER or IR. Compared to what? Does it depend only on the final position, or on the path we used to get to the final position?

Second point: whatever humeral rotational position means, the affect on the GH joint will depend on the flex/abduction angles. Rotating at abduction of 0 feels very different than rotating at abduction of 90.

On lifting technique: First issue is simply being in position to exert maximal vertical force. Horizontally abducting (in Arnold press) into scap plane helps with this, since it better engages the lateral delt. It may also change some other leverages and/or change some muscle lengths to find a better place on the strength-length curve.

Separate from max force, we also want to minimize various moment arms, in order to minimize the need for even more muscle to counteract them. E.g. keep elbow under wrist. (Which is why cuban press is not optimal for force generation, so you use lighter weights.)

And, when we have max force, and minimal secondary moments, we still want to stabilize the shoulder by isometric torque (possibly) resisted by ligament torque, which will then keep the GH joint centered.

What that means for cueing, I haven’t quite figured out yet 🙂 I do think shrugging at the top of a press is the right way to go.

“My point is, we (or at least I) do not have a clean definition of what it means to “be in humeral rotation”. I understand humeral rotational *motion* when the flexion/abduction angle is fixed. What I don’t understand is the defintion of *being* in ER or IR. Compared to what?”

Compared to neutral humeral position. Whether the humerus “is,” or can be said to “be,” in internal or external rotation depends upon the definition of neutral humeral position. Neutral humeral position or orientation can be defined as an absence of humeral/shoulder rotation relative to anatomical position.

Let’s say that you elevate your humerus to ninety degrees in the frontal/coronal or sagittal planes. This is “strict” abduction or flexion, respectively.

(More generally, you could say that abduction or flexion are examples of elevation within two planes that both 1) are perpendicular to the transverse plane and 2) pass through the humerus. These planes intersect perpendicular to each other at a line that runs through the middle of the head to between the legs. There are infinitely many planes like these two. Moving the humerus from one of these planes to, or through, other similar planes can be designated “horizontal” motion. Movement in line with one of those planes can be referred to as “vertical” motion. Strict–see above–simply means a motion is not a combination of vertical and horizontal components).

Now, if you don’t rotate your humerus during vertical motion, then your humerus is still in neutral position in either plane. However, despite both being strict vertical movements without any rotational movement, the orientation of the arm at ninety degrees of abduction is visibly different from that of ninety degrees of flexion. Assuming no radioulnar rotation (supination or pronation), in the former case the palms are facing down, while in the latter case the palms are facing each other. Put another way, in the former case the thumbs are pointed forward, while in the latter case they face forward. In fact, neutral humeral position looks different in all the intermediate planes between the frontal and sagittal planes, as well.

In moving the humerus strictly horizontally from neutral humeral position in the frontal plane to that of the saggital plane, and vice versa one has to respectively IR and ER the shoulder. But rotating the humerus to reach a neutral position in a different plane does not mean you are “in” ER or IR. You are in neutral for that plane, no matter how you got there. You can, however, be rotated relative to neutral within that plane–but only within that plane. As you move horizontally, whether strict or with a combination of horizontal and vertical motion, neutral changes. In this sense, we cannot speak of truly “being in” IR or ER without reference to the neutral humeral position of the plane you are currently in. This may sound overly complex, but these different neutral positions are entirely predictable if you use the frontal and saggital neutral positions as reference points. And remember: neutral positions don’t change with strict vertical motion; they only change when there is also or solely a horizontal component to the motion. Of course, your humeral proximity to neutral tells you NOTHING about whether you are near end range IR or ER, as this does change with vertical motion because of shoulder anatomy.

“Does it depend only on the final position, or on the path we used to get to the final position?”

Only on the final position. The shoulder can rotate as it travels, but whether you are in rotation relative to neutral will change as you move horizontally. There is no “being” in ER or IR without reference to neutral. And the path taken to get there does not change the relative position.

On second thought, I should have waited to read my comment in the morning before posting this. Just realized there was a fundamental flaw in the reasoning.

The Arnold press actually starts externally rotated, moves through horizontal abduction, abduction and flexion finishing in external rotation where it began.

Overhead position is external rotation, no matter how you look at it. You can create torque by trying to rotate ext or int, but the position is external rotation.

Its easy to understand if you internally rotate your arm and attempt to raise it overhead. Watch your bicep rotate externally…. It actually hurts a little for me to even try this.

Now this is getting interesting! Andrew, thanks, and I must pick your brain. My curiosity is on red alert!

Scroll up to Steven Trolio’s video screen shot. Don’t play the video, just look at the picture. Does this mean that Steven’s shoulders are in external rotation just because they are overhead? And if he turned those elbow hard to the front, as in a simulated “chin up” position, would he then be in, dunno, “super-external rotation”?

(And if overhead itself is XR, then why would Starrett have video after video about XRing the shoulder? Why not just go overhead any old way, and thus, be XR’ed, lol!)

To me it looks like his humeral head is about as maximally internally rotated as possible in the socket, even while the shoulder is fully flexed.

If you think of the shoulder like the hip, the degree of flexion or extension is separate from the issue of rotation, right? So with a fully flexed hip you can IR it (toes to the middle), and XR it, toes to the outside. Now with a fully extended hip, you can just the same IR it, and XR it.

It’s a bone, it fits into a capsule, and it turns in the capsule, right? The shoulder is different?

Sorry to hit you with so many questions, this has been a mystery to me for as long as I can remember, and NOBODY wants to discuss it b/c it’s so darned confusing!

I think what we are missing it that external rotation doesn’t mean end range external rotation. I would agree that we are nowhere near end range IR in any overhead postion, but not at end range external rotation either like we are in the start of the press which goes back to my original comment about the press needing minimal internal tension to be successful. I think as long as the forearm is close to vertical and not pointed backward at the end of the press. This may be what Kelly wants and what is best for the shoulder. I certainly don’t believe the press is ideally just moving through flexion (like in an exaggerated Kelly starrett groove) or pure adduction, like you see in the flared bodybuilding press. The strict overhead press has a noticable horizontal component as it starts at the hand in front of the shoulder and then finishes with the hand above it. This is another reason why horizontal abduction/IR must take place.

It is impossible to be anywhere close to end range internal rotation in any form of end range flexion both in the hip and shoulder. I think we just just accept that the shoulder is in more external rotation/adduction at the start and less so at the end that would be simple enough. The coupled motions certainly complicate things but regardless of terminology I think we all understand that “flaring” and “tucking” represent these positions. Torque would essentially make the goal of the least amount of changes between these two positions physically achievable (creating a tucking force) but will be inneffeictive for actually moving the load as it will change the mechanics and leverage and create high internal tension.

“I think as long as the forearm is close to vertical and not pointed backward at the end of the press + it’s a proper press***.

According to this study, I’m wrong about ext rot with flexion.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed/6463110/

I need to study this more. 🙂

If you look at a base ball pitcher at early and late cocking positions, they are in external rotation… Hyper external rotation.

If you lift (abduct) your arm from there, you are in external rotation, overhead.

Now, if you hold your arm in a sling position you will be in adduction/internal rotation. Keeping your elbybone bent flex the shoulder… You are now in the position for a one arm French press/triceps extension….. Which appears to be fully internally rotated.

I hope that clears things up…lol

Great article! These are the posts that drive the profession forward.

Ah, Andrew’s last comment inspired the following idea.

His example, and mine above, clearly indicate that the degree of humeral rotation depends on the context of degree of flexion and abduction. That is, you can take a position where the humerus is in ER, and by simply flexing and abducting (*without* additional humeral rotation) move it to a new position where it is now in IR.

Upshot: flexing or abducting can intrinsically affect humeral rotation. The idea you can flex or abduct without rotation is simply a bad concept.

So, I propose the following definition for determining the extent of rotation. Move the arm into some position of flexion/abduction. Now, without any flexing or abducting, simply rotate the humerus to find the full range of IR and ER. Given that full range, you can now say if the orginal position was closer to the max IR or max ER. This gives a consistent definition, and does not depend on the motion that got the arm into position.

Great discussion, Andrew, Tyler, and Bob!

Bob, you and I are basically on the same page. Here’s the schema that I found myself working from, but frankly I don’t know if this is how PT folks, and gymnastics folks, etc. view the matter at all:

Whatever flexion/extension/adduction/abduction action is going on in whatever plane…what position is the humeral head wedged into the socket, and from that position, where on the continuum of rotational “room” is it located?

Read this thread for some more ultra-confusing nomenclature zaniness. Skip to the second post from the bottom of page 1 where the fun begins:

https://www.gymnasticbodies.com/forum/topic/6011-important-pull-up-question/

Exactly!

On the gymnasticsbodies post by RandomHavoc, he is saying that, as you hang, you should create torque in your shoulders so that, if the bar were malleable, your palms would turn to face each other. Which I think is correct, that is the natural inclination you would have on the eccentric phase of the arnold press.

On shoulder packing for pullups: I think you want to maintain enough tightness so the humerus does not get pulled out of the glenoid. Don’t go so loose as to hang on your joint capsule! However, that is very different from whether or not you should rotate and elevate the scaps. Which I think you should, because the more the shoulder ROM is produced by scap motion, the less it is produced by GH motion, and it is the GH extreme motion that produces impingement. If you rotate up your scaps during the pullup decent (or press ascent), you move the acromiom out of the way.

Right, Bob, this is the “pull from the pinkie” idea, and I like it a lot. Or torque off the bar. (By the way this seems to happen pretty automatically when you initiate the action from the elbow and not the hand…ala “hands are just hooks”, or “elbow chop” cue.)

My dilemma is this then, if winding externally (supinating ) is appropriate on the way down, then doesn’t it follow that winding internally (pronating) is appropriate on the way back up?

And my own personal experience is… yes! It feels natural and congruent to press like Bruno and Klokov, i.e. untuck the elbows into a flare under the bar and drive it up. And the finished position therefore ends up with the elbows and armpits pointing to the side, and definitely not to the front.

this is interesting, let me ask you this: are you a shrugger or a packer?

it seems to me that the people who advocate IR also use the traps shrug

approach while people who advocate ER use packed shoulders.

this is just another aspect of the same old discussion.

I know personally if don;t pack AND ER I end up impinging, for shruggers

the exact opposite is likely true.

@Sol: Great, great observations! You’re on the money, here. The IR approach goes hand in hand with an “active shoulder”, and the XR approach goes hand in hand with a “packed shoulder”.

Think it through further, (and believe me, I have! ha ha), this is basically a scapular movement corollary to the commonly observed “IR up, XR down” movement pattern observed and illustrated in the article:

IR humerus, Upwardly Rotate Scapula into Shrug on the way UP.

XR humerus, Downwardly Rotate Scapula into Pack on the way DOWN.

BTW, I have a theory that locking into the ” XR/pack” part of the pattern for the whole UP/DOWN cycle may be an attempted workaround to try and closed chain extend the T-Spine via scapular action. If the T-Spine is switched on via the spinal extensors along with braced abs to control the lumbar, the scaps are then freed up to glide around the ribcage, and thus the humerus has clearance under the acromion.

Anyways, after lots and lots of trial and error, and lots of shoulder shredding pain, IR/shrug turned out to be the most comfortable, natural, and effective approach for me personally.

Reading into the Chinese OLY overhead philosophies from the “All Things Gym” articles, it appears they like:

1. IR

2. Shrug

3, Slight forward head posture.

So yeah, basically the exact opposite of everything you’ve ever been told, lol!

Try an OHSQ, an exercise that is fantastic for total body mobility, and do it both ways. You will know right quick which approach is best for you.

Listen, whatever works! Sometimes you gotta try different approaches.

Btw, I’m fully aware that all of this is just thoughtful word salad unless you can coach an intelligent 6th grader performing their first press or pull up with:

1. A cue

2. An explanation of the intention of the cue.

3. A slow, step by step, physical execution of how the cue plays out into actual movement.

4. A biological basis, i.e. your shoulder is going to grind into some ligaments unless this happens, or this is the position where bones fit together the best.

But then again, that’s what $1,000 seminars are for, I guess. (Yeah…I went there.)

If you’re learning from Klokov or other world champion I guess their time may be worth the 1000$, but still, damn that’s expensive.

Mladen and Bob make excellent points.

In your article you often confuse or miss what rotation is in the shoulder joint.

Bob describes what is in every good anatomy book (so everyone writing articles about the shoulder should know) -> in a joint with 3 degrees of freedom you can change your rotation by using the other degrees of freedom without ever rotating the joint (by simply flexing / abducting etc in 90° motions you end up in the same plane with 90° of rotation).

In many of your examples there is no internal rotation as you state, even external rotation in the shoulder, mostly rotation in the elbows taking place.

Regarding the full flexion in the shoulder like overhead pressing : anatomy (that may differ somewhat in individuals) would clearly be better with external rotation to clear the tuberculum, position the biceps tendon and force couples of rotator cuff muscles better (cant understand noone here talks about the different force vektors in internal/neutral/external rotation in correlation with scapular angle -> IR maximising upward translation of humerus).

What top athletes do is no reference for healthy lifting – they want peak performance no matter what plus you dont know their individual settings.

Internal rotation above 80° of abduction is strongly correlated with abuse of your shoulder joint (just look up lots of studies refering to it)

Before lengthy discussion of the pros and cons of int/ext rotation in various angles in the shoulder one should simply read and study the literature to have understanding of the motions/terminology and problems.

Tom, thanks. Agree, I like Mladen and Bob’s very positive contributions. I also like their helpful and constructive tone. I’m learning a lot here. Which is the whole point of the post and discussion.

Tom, you seem highly knowledgeable. I think you could actually help me and other confused lifters out here.

Would you mind making a detailed, step by step video in which you slowly, patiently, and thoroughly integrate your 80-degree abduction science and such, into a technically perfect and safe, step by step, loaded overhead press using barbell, and then again with dumbbells?

If you could explain the various rotational positions along the way, that would be awesome as well.

If you have time, could you do the same with a fixed bar pull up, and then again, with free motion rings? There are a few of us trying to learn more who aren’t quite sure about some of this stuff, and you could potentially be a big help!

Thanks, Tom!

Derek,

Nice article and to all, a very interesting conversation. So much to say yet I want to keep this as short as possible. One thing to remember is that everyone can have their own opinion but not everyone can have their own facts. I have looked for studies (not recently) re: the overhead press but never found anything significant (if anyone on this thread knows of any relevant scientific articles on the overhead press, please post it). Therefore like everyone else I can also only provide an opinion on this subject matter but here are some facts to consider prior to the posting of my opinion:

1. All joint movement requires rolling, gliding, and rotation. Some include tilting.

2. 180 degrees of arm elevation is due to a combined 120 degrees of humeral elevation and 60 degrees of scapula rotation which is dependent upon the scapula force couples as well as the rotator cuff/deltoid force couple

3. The hip and the shoulder although both ball and socket joints are not exactly the same. The shoulder has greater mobility vs. the hip as the hip has a greater component of bony stability when comparing the acetabulum to the glenoid.

4. Studies commenting on passive range of motion (PROM) are valuable but active range of motion (AROM) is often different.

5. The most congruent position of the shoulder for overhead motion is the plane of the scapula

6. The pathway utilized to generate the most muscular force overhead is the plane of the scapula as this plane provides the greatest length tension relationship at the shoulder.

7. The main function of the rotator cuff is to maintain the head of the humerous in the center of the glenoid throughout shoulder ROM, not rotate the humerous (which it also performs).

8. The glenohumeal ligaments contribute to shoulder stability at various shoulder ROM’s. This is especially true of the inferior glenohumeral ligament which forms a “hammock” for the humeral head to assist in anterior and posterior stability.

To keep this as short as possible I will mainly address overhead pressing type exercise performance. In review of the video provided by Derek of Dmitry Klokov you will observe that at the time he makes his “catch” to the time he concludes the lift overhead with his arms fully extended, his elbows are pointed outward and he is externally rotated at the humerous. In fact he is initiating his overhead movement in the plane of the scapula (I have written about this on Bret’s website). In review of the position of Klokov’s humerous (humeral head to elbow) it appears to be externally rotated (elbows out) throughout the lift. Although the elbows (humerous) may internally rotate slightly at the conclusion of the lift, this IR is relative to maximal humeral external rotation position during the exercise performance, but still maintains a position of humeral ER (elbows pointed outward). IMO an internal rotation moment does exist at the conclusion of the exercise performance that is additionally addressed by the forearm (radius and ulnar) which adjust for the pronated hand position + shoulder ER that occurs throughout the exercise performance

To successfully achieve an overhead arm position we need to externally rotate the humerous so that the greater tubercle is cleared from the inferior aspect of the acromion. Try assuming a “racked” position with the elbows pointed straight ahead. Now completely extend your arms overhead maintaining a pathway of pure flexion (keeping the elbows pointed straight ahead). Can you completely straighten your arms overhead?

As far as pulling from an extended arm position (i.e. pull –ups), since our hands are gripping a fixed object it is the combination of adjustment of the forearm (ulnar and radius) along with the humerous that assist to achieve a successful exercise performance. IMO one reason why we draw the elbows close and IR in an overhead pulling exercise event is because our biceps and brachialis contribute to the success of the exercise performance. The biceps is the main supinator of the forearm. However, we aren’t supinating the forearm as our biceps fires but due to the “overall” fixation of the forearm with the locked hand (closed chain) position on the chin-up bar the contracting biceps as well as the lats (a humeral adductor and IR) assist in a close elbow IR position. The joint position at the elbow assumes a similar joint contact surface area if the humerous is fixed and the forearm supinates or if the forearm is fixed and the humerous internally rotates. The same analogy may be seen at the tibial and femoral condyle joint surface contact area when comparing a knee extension to a squat exercise performance.

Just my opinion

Rob Panariello

Derek,

Nice article for thought and to all, a very interesting conversation. So much to say yet I want to keep this as short as possible. One thing to remember is that everyone can have their own opinion but not everyone can have their own facts. I have looked for studies (not recently) re: the overhead press but never found anything significant (if anyone on this thread knows of any relevant scientific articles on the overhead press, please post it). Therefore like everyone else I can also only provide an opinion on this subject matter but here are some facts to consider prior to the posting of my opinion:

1. All joint movement requires rolling, gliding, and rotation. Some include tilting.

2. 180 degrees of arm elevation is due to a combined 120 degrees of humeral elevation and 60 degrees of scapula rotation which is dependent upon the scapula force couples as well as the rotator cuff/deltoid force couple

3. The hip and the shoulder although both ball and socket joints are not exactly the same. The shoulder has greater mobility vs. the hip as the hip has a greater component of bony stability when comparing the acetabulum to the glenoid.

4. Studies commenting on passive range of motion (PROM) are valuable but active range of motion (AROM) is often different.

5. The most congruent position of the shoulder for overhead motion is the plane of the scapula

6. The pathway utilized to generate the most muscular force overhead is the plane of the scapula as this plane provides the greatest length tension relationship at the shoulder.

7. The main function of the rotator cuff is to maintain the head of the humerous in the center of the glenoid throughout shoulder ROM, not rotate the humerous (which it also performs).

8. The glenohumeal ligaments contribute to shoulder stability at various shoulder ROM’s. This is especially true of the inferior glenohumeral ligament which forms a “hammock” for the humeral head to assist in anterior and posterior stability.

To keep this as short as possible I will mainly address overhead pressing type exercise performance. In review of the video provided by Derek of Dmitry Klokov you will observe that at the time he makes his “catch” to the time he concludes the lift overhead with his arms fully extended, his elbows are pointed outward and he is externally rotated at the humerous. In fact he is initiating his overhead movement in the plane of the scapula (I have written about this on Bret’s website). In review of the position of Klokov’s humerous (humeral head to elbow) it appears to be externally rotated (elbows out) throughout the lift. Although the elbows (humerous) may internally rotate slightly at the conclusion of the lift, this IR is relative to maximal humeral external rotation position during the exercise performance, but still maintains a position of humeral ER (elbows pointed outward). IMO an internal rotation moment does exist at the conclusion of the exercise performance that is additionally addressed by the forearm (radius and ulnar) which adjust for the pronated hand position + shoulder ER that occurs throughout the exercise performance

To successfully achieve an overhead arm position we need to externally rotate the humerous so that the greater tubercle is cleared from the inferior aspect of the acromion. Try assuming a “racked” position with the elbows pointed straight ahead. Now completely extend your arms overhead maintaining a pathway of pure flexion (keeping the elbows pointed straight ahead). Can you completely straighten your arms overhead?

As far as pulling from an extended arm position (i.e. pull –ups), since our hands are gripping a fixed object it is the combination of adjustment of the forearm (ulnar and radius) along with the humerous that assist to achieve a successful exercise performance. IMO one reason why we draw the elbows close and IR in an overhead pulling exercise event is because our biceps and brachialis contribute to the success of the exercise performance. The biceps is the main supinator of the forearm. However, we aren’t supinating the forearm as our biceps fires but due to the “overall” fixation of the forearm with the locked hand (closed chain) position on the chin-up bar the contracting biceps as well as the lats (a humeral adductor and IR) assist in a close elbow IR position. The joint position at the elbow assumes a similar joint contact surface area if the humerous is fixed and the forearm supinates or if the forearm is fixed and the humerous internally rotates. The same analogy may be seen at the tibial and femoral condyle joint surface contact area when comparing a knee extension to a squat exercise performance.

Just my opinion

Rob Panariello

Rob, I was hoping you would join in here! Thank you so much.

May I pick your brain a bit?

Rob, if someone has dumbbells locked out overhead, with the bells facing directly forwards (think “Touchdown!” signal), and then twist the dumbbell to facing sideways/horizontally, (think, “Freeze! Hands overhead!”)….did they just perform an internal shoulder rotation?

Put another way, once the humeral head clears the greater tubercle from the inferior aspect of the acromion (accomplished through XR), the humerus continues to rise along with necessary scapular upward rotation.

At that movement window, (around 135-180degrees), is there now further potential for rotation in either direction, external or internal?

This seems to be what Starrett is saying and demonstrating, and what the Chinese coaches are trying to convey in the All Things Gym piece, although they are cueing in different directions.

Once the humerus approaches overhead, it does seem to have “new rotational capacity” thanks to the roll and glide that has just occurred. Again, I may be not grasping their intentions fully, though!

Derek,

I understand your thought process. To answer your question yes, and I would give you 2 scenarios of how to achieve this. So with your pinky’s facing forward holding a dumbbell in the “neutral” position you can (a) pronate your forearm to achieve the “twisting” of the dumbbell and likely have some IR of the shoulder or (b) lock the elbow and internally rotate the humerous to achieve the same dumbbell position.

IMO the barbell is a different animal. The hands are fixed with the forearms pronated. So we have to abduct, horizontally abduct, and ER the humerous to achieve the plane of the scapula. We need to to clear the greater tubercle through ER during the lifting process to conclude with the arms overhead. The difference is with the dumbbell the hands aren’t fixed in pronation and the hands/upper extremities are free to move and assume various positions. The barbell is a different animal as we have our hands attached to a fixed object (barbell) in pronation and need to clear the bar from an anterior position to the face/head with an appropriate upper extremity mechanism to get the bar to a concluding position directly overhead. I think part of this mechanism occurs due to fixed hands, with the adaptation of the radius and ulna at the proximal elbow joint along with humeral rotation as the humerous elevates overhead.

As I stated I understand where you’re coming from but IMO DB’s and BB’s are 2 different animals and shoulder mechanics may be similar or completely different depending upon hand and shoulder position at the initiation and pathway of the overhead movement. Review your video of Kolkov’s lift again. How does he assume his racked position without ER of the humerous? How does a barbell with a fixed hand position change from this racked position (being anterior to the face/head and already in ER) to move superiorly and posteriorly to conclude to a position directly overhead without ER of the humerous? How about the snatch?

Just my opinion

Rob Panariello

Derek,

To address your next post hold a barbell directly overhead with your arms fully extended and try to IR your humerous. Can you really succeed or is there an IR moment? In Olympic lifting at times we will provide a cue to “stretch the bar”. Are our arms actually moving as additional force is applied to the bar?

With load overhead the rotator cuff is applying high compressive forces to maintain the head of the humerous in the glenoid, the scapula is rotating to assist to maintain the head in the proper position yet the rhythm now changes as the scapula needs to provide greater stability for humeral mobility. With rotation the joint capsule tightens and provides additional stability (think of holding a wet wash cloth and then twisting it to ring it out).

All of the people you have mentioned are intelligent professionals, however, as I am providing my opinion so are they unless they may also provide scientific evidence substantiating their comments. If they can I am very interested is seeing it.

Just my opinion.

Rob Panariello

Thanks, Rob. I love the way you lay it out. Admittedly this gets tricky.

Let’s tackle the fixed bar. What I think happens is the elbow will flare or tuck in response to a rotation at the shoulder against a fixed wrist. This is the rationale behind “tuck the elbows” on a bench press, (different plane, but same principle), to control the internal rotation of the humerus.

(Starrett believes in this principle so fully that he has a video advising against using a false grip on a pull up, wrapping the thumb is suggested to better to use the bar as an anchor to “torque” against.)

As an example let’s look at rotation at the hip on a SQ, (yes I see the two joint capsules are not identical, but I think this analogy holds up):

When squatting, the feet are wedged to the ground. Thus externally rotating the hip will not move or turn the feet. What it will move is the KNEE which is in open space and thus flares outwards. This is the valgus solve that we have all covered extensively.

When the distal end of the kinetic chain cannot move due to friction, a point in the middle of the chain will move.

What I think is happening with Klokov is that with the hands locked to the barbell, once he clears the tubercle in XR, he IR’s hard, torques internally off the bar, which then flares the elbows outwards along with a lateral delt force also acting on the elbow, in a similar fashion that the knees flare outwards on a SQ due to hip external rotation against a “fixed floor”.

My guess is that if you put sensors on the bar under Klokov’s hands, the sensors on his thumb side are lighting up as those elbows flare. He is “breaking the bar” internally. If the bar broke at this point in time his thumbs would turn medially.

Just spitballing, and I’m not sure how you would go about proving this. What I do know is if you have a movement intention of “turn to the middle”, that’s exactly what it looks like, and that ends up in a different finish position then a a hard supination mindset all the way through.

Hopefully this makes sense. And obviously, Just my opinion. 🙂

FWIW, here is a link to some Klokov seminar notes.

http://www.allthingsgym.com/klokov-ilin-polovnikov-weightlifting-seminars/

Midway down the page:

“5) They actually said NOT to put your shoulders in the externally-rotated, elbows-down position in the overhead squat like they instruct at the CF Level 1 seminar. I’m pretty sure they even said “elbows face back”, and keep the wrist neutral.”

And if you plow through the 101 comments, you will get a sense of the collision of different philosophies on all kinds of technical points.

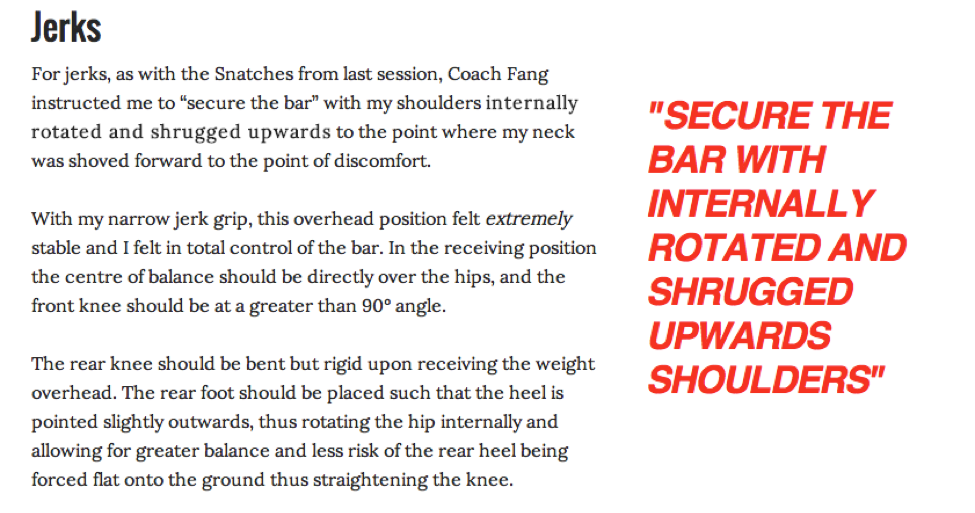

A far more pertinent link to the discussion is this one:

http://www.allthingsgym.com/larrys-chinese-weightlifting-experience-part-1-snatches-squats/

You don’t have to read more than half a page to see aggressive physical positioning of internal rotation being coached for overhead (snatch, and later jerk).

And i do mean aggressive!

Derrick, email me if you wish 😛

Hey Sven, I shot you an e-mail. Good to hear from you, my friend.

Derek,

I agree that this is tricky as I am providing an opinion as well. I am not aware of any scientific biomechanical documentation that provides us with an answer and until that information is presented (it may exist but I haven’t seen it to date) then everyone is providing an opinion.

With regard to your bench press analogy I understand what you are expressing but the con to that statement one may argue is that when performing the bench press the scapula are retracted so the athlete has a platform from which to push. This retraction does “tuck the elbows” however as the humerous is extended via scapula retraction, based on the convexity of the thorax one could argue that the humerous ER’s.

In your squat example ER of the hip will move the knee, the point in the middle of the chain as you state. In this example even though the feet are fixed to the ground surface area isn’t there a force (moment) at the ankle joint? Isn’t the elbow the “middle joint” between the fixed hands at the barbell and the shoulder? However, just like the ankle joint has a moment, isn’t there a force at the ulnar and radius that may be compensatory to an IR moment at the shoulder vs. actual shoulder IR occurring?

I respectfully disagree with your statement re: Klokov. I don’t think he consciously tries to IR hard, I believe a lifter just drives the heavy weight overhead, as that is their only focus. The technique they have performed 1,000’s of times and the body being the amazing machine that it is takes care of business.

If you put sensors on Klokov’s hands IMO the force would be more evenly distributed along his hands so that all effort/generated force is applied vertically for an efficient and optimal overhead lift. If greater forces were recorded under his thumbs so that he could “break the bar” then the direction of his generated forces would be vertical and angled and are not applied maximally and efficiently to the barbell to move it vertically.

To efficiently move the bar vertically I believe an adaptation does occur. Is it at the forearm as in the previous ankle statement? Is it an internal rotation moment or do we actually have IR of the humerous? I do believe we have an IR moment at the shoulder as the lift continues overhead. The question is what is the compensatory action for this moment for the most efficient application of force to the barbell to drive the barbell effectively vertically?

Just my opinion

Rob Panariello

Rob, first, a sincere thanks straight away for your time and the intelligent, thoughtful perspective that you are generously providing. I learn from differences of opinion, and when it comes from you and Bret, I really look hard at where I’m going astray. Because I know that you both have no agenda whatsoever, except getting to the real world truth of any matter.

Rob, before I even get rolling on this, please let me explain something. I didn’t come up with any of this rotation/torque stuff. None. Absolutely 0% came from my brain. And I’m not pro/con on any technique that is effective and safe.

100% of it came from reading various expert opinion, and watching videos, etc.

Most of my life was spent just like you said with Klokov, just lifting bars overhead and trying to get stronger. I just started doing behind the neck presses again. Why the hell did I ever stop doing them to begin with? They’re awesome. They train scapular retraction in a stability capacity, which is qualitatively different than training the same function in an agonistic capacity, i.e. rows, face pulls, etc. They also train as pure a scapular upward rotation pattern as you can do.

So they work well for me. Are they for everyone? Of course not. Point is that, it was really only when I started reading more and more, that I began to notice that a lot of the stuff that was advised, that was theoretically really important, was clearly not what I was doing.

Never in my mind did it occur that I should focus on “supinating”, or “torquing”, or “packing” or “rotating”, etc. I was just on autopilot lifting stuff.

100% of this rotational theory was gathered from reading ‘expert’ sources, including, but not limited to: Pavel’s book and blog, “corkscrewing”, watching literally hundreds of MWOD videos, reading Diesel Crew’s Jim Smith call for an “elbow correction” on a bench press. Reading Boris from SQuat RX call for “do the Fonzie”, reading “break the bar” about a million times, etc.

There are too many bright, seasoned veterans extolling the virtue of something for it to be dismissed.

On that basis, then, I am trying to figure out what the intention of the cue, again, that I did not invent, but through sheer repetition has filtered into my brain. There is a guy on BC’s Facebook page who said that he felt “guilty” for ending up in IR at the top of an OHPR. I myself have felt “guilty” b/c my elbows flare, and yes, my shoulder internally rotates on my bench press.

I was busted for having a forward head posture on my OHPR. The Chinese exhibit a forward head posture, it sets up the upper traps to support the load. Again and again, we are admonished to guard against “upper trap dominance”….So it’s on this perpetual basis of confusion and disconnect that I try to make sense of things.

What is Klokov thinking when he presses overhead? I don’t know either. What I do see is his elbows flare wide quickly and efficiently after he clears the acromion, and then drive the elbow straight up against the load. If I screen grabbed his finish position, and compare it to Starrett’s recommended finish position, then they look like they are arriving with a different motor pattern.

What I see Klokov doing with his elbows is not unlike what I see bodybuilders doing when they lift with dumbbells. It is exactly how I press a barbell, I press dumbbells in the scapular plane, and IR slightly at the top.

All of this works great unless I unfortunately try to “corkscrew” my shoulder on the way up, in which case I have immediate discomfort.

Now if you gave Klokov a pair of heavy ass dumbbells, I suspect that he would arrive at the top with the bells facing in a horizontal direction. Now some might end up at the top with bells pointed forwards in a neutral “touchdown” position. Personally, I say, whatever feels best to you, run with it.

Now would this entire difference of position be explained away by various moments through the forearms and elbow and wrist. I say, doubtful. There is some difference in the end position shoulder rotation.

Take that aside, though. Let’s go to cueing, or coaching. You are coaching an intention. The intention may end up being a very small difference in actual, measurable rotation. But the sequencing of the motor pattern especially as it pertains to joint stabilization, the CNS directive, is very different.

If I take a 12-year old and tell them to press the bar and “wind up the shoulders” and demonstrate it as such, their press is going to be executed very differently than if I say, “as the bar clears your forehead, drive your head through and flare the elbows hard under the bar”.

The difference in shoulder rotation at completion may be a matter of less than 35-degrees, but the process of getting their is now a big-time different move.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nNExilo9GSI

Here’s a Starrett push up video. I’ve been doing push ups for over 40-years. Hundreds of thousands of push ups. Never in my life did it occur to me that my shoulder was unstable if I got to flexion in internal rotation. Who knew?

Look, I’m not trying to diminish Starrett in any way. A lot of his stuff has been enormously helpful to me. He is bright, passionate, charismatic. You just don’t get that kind of following without some excellent wisdom behind it.

In some ways, Rob, your questions match my own, and I ‘m in the uncomfortable position of trying to explain ideas that I didn’t create, or fully grasp, or necessarily agree with.

I THINK we are primarily talking about a moment more than an movement on most of this rotational stuff, but frankly, Rob, I’m not sure. This is one of the questions that I am posing to the S&C braintrust at large, and this query is expressed directly in the article. The entire article is essentially a giant question, a plea for more thorough explanation beyond buzzwords, and arcane debates about degrees of rotation in the “anatomical” position.

Derek,

I have enjoyed the conversation as I enjoy a good thought process anytime. As you know I have not provided you with a definitive scientifically proven answer either, nor am I sure that anyone can. That said we also cannot ignore that coaching contains a component that is an art form in of itself, with the addition of science, IMO is the pathway to an outstanding coach.

I think there are occasions where the yellow caution flag goes up and we don’t see it. For example a few years ago my good friend Johnny Parker called me to tell me he had read a newspaper article about a college football player who was NOT a competitive powerlifter or weightlifter and reportedly squatted 800 pounds. Johnny had a concern about football players focusing on excessive strength levels vs. power and speed (which is dependent upon strength) and asked me to spread the word about risk vs. reward in these situations. This is what prompted my article “How much strength is enough?”

When I studied in Bulgaria with the National Weightlifting team under Head Coach Ivan Abadjiev it was the spring prior to the Olympic Games. His athlete’s lifted 3 times a day for 1 hour and performed 4 exercises, the back squat, the front squat, the clean and jerk, and the snatch. They lifted singles and doubles and no less that 20Kg’s from their PR. Although I did learn much on this trip, being the Head S&C Coach at St. John’s University in New York at that time, how was I to possibly to apply this program design to my athletes? I would have loved to have been in Bulgaria 1 or 2 years earlier to witness how Abadjiev’s athlete’s got to this point. Although he told us I would have liked to witness it.

To be totally transparent I do not train world class sprinters, weightlifters, powerlifters, or bodybuilders. I train athletes for optimal sports performance from the high school level to Pros with $100,000,000 contracts. We should strive to be the best coaches that we can be but that said, I think at times we forget that we are using the principles of weightlifting, powerlifting, etc…. to enhance the physical qualities and athleticism of our athletes for optimal athletic performance. Unless the athlete is actually a competitive weightlifter, powerlifter, or body builder why would we try to make weightlifters, powerlifters or body builders out of them?

Many of the athletes I train have had surgery or have a specific pathology that needs to be addressed during training, and so they come to me with the confidence that I will implement the necessary modifications, if any are necessary, during training so that they don’t exacerbate their condition and still obtain optimal levels of athletic performance. Often times I do apply SAFE modifications that are necessary during training resulting in variations of lifting techniques and still conclude the training program with success. My point is that many athletes are successful on the field of play displaying different throwing, hitting, swinging, shooting, etc. techniques. There are optimal lifting techniques, however with variances in an individual’s anatomy, medical history, etc. sometimes we just need to do the best we can and are more often than not, are still successful.

Maybe your push-up style was different than the one describe by Kelly, but did your differnet push-up style result in an injury? When it comes to obtaining information sometimes we are so focused on finding “gold” that as we are digging for this gold we don’t see all of the diamonds, ruby’s, and other gems right before our eyes. Sometimes we focus so much on what everyone is telling us to do, we forget the great benefit to just loading the bar and lift. How’s that for a concept?

Derek, to be clear I’m not saying that we shouldn’t try to enhance our knowledge and be the best we can be as I’ve also stated that it’s just as important to get a callus on our butt from studying as it is to get callus’s on our hands from the barbell. However, we also can’t ignore, the individual’s that we are working with, their athletic goals, and the lifting techniques and program designs that are best suited for them. When mining for gold, don’t miss the other jewels that will stare you right in the face.

Just my opinion

Rob Panariello

Great dialogue gentlemen! I’ve enjoyed the discussion. I skimmed through the comments and tried my best to keep up. I also checked out around a dozen published articles, which I’ve linked below (many offer free access). Here are some notes/thoughts:

1. There is discrepancy as to whether the humerus medially or laterally rotates as it moves overhead into flexion. I found several articles stating medial and several stating lateral. I’d like to know the answer to this.

2. . If the flexion/abduction occurs in the scapular plane, it is possible that there is no axial rotation that occurs with the humerus (see quote below)

3. Motion should not be confused with moments, as one can exert muscular rotational torque without rotation in that direction actually taking place (to create more stability, for example)

4. An active shoulder (shrug, or scapular elevation/upward rotation) seems to be espoused when producing internal rotation muscle torque, whereas a packed shoulder (limited scapular elevation) seems to be espoused when producing external rotation muscle torque

5. Wrist rotation can create the illusion of shoulder rotation when using db’s or rings, and can mask it when using bb’s (so we must pay close attention to what’s going on at the actual shoulder joint)

6. The shoulder joint is complicated because you have several joints moving in all sorts of directions, which leads to complications and difficulty in explaining the biomechanics.

Check out the quotes from this article: http://www.jospt.org/doi/pdf/10.2519/jospt.1993.18.1.342

“The shoulder complex consists of the clavicle, scapula, and humerus; the glenohumeral and acromioclavicular (AC) joints that unite them; and the sternoclavicular (SC) joint, the only

connection of the complex to the axial skeleton. In addition, a scapulo-thoracic and a subacromial joint are often included in anatomical descrip tions of the shoulder complex. Together, these articulations provide

the shoulder with a range of motion that exceeds any other joint mechanism. Full mobility is dependent on

coordinated, synchronous motion in all joints of the shoulder complex. This wide range of mobility, together with elbow motion, allows positioning of the hand anywhere within the visual work space.”

“The glenohumeral joint is described as having three degrees of freedom: flexion/extension, abduction/adduction, and rotation. The amount of glenohumeral abduction in the coronal plane is limited to 60- 90″ if the humerus is maintained in internal rotation (1 2,43). This limitation is due to impingement of the greater tubercle of the humerus on the acromion process and tension in the inferior glenohumeral ligament (28). If the humerus is allowed to externally rotate, abduction range increases to between 90 and 120″ (1 2,43,67). Elevation of the humerus in the sagittal plane is accompanied by medial rotation of the humerus (8,33,53). According to Cagey et al (28), the medial rotation occurs because of increasing tension in the coracohumeral ligament as the humerus flexes in this plane. When the humerus is elevated in the scapular plane, a movement termed scapular plane abduction, lateral rotation is not required to prevent the greater tubercle from impinging up011 the acromion (2533). In addition, the glenohumeral joint capsule is not twisted when elevation occurs in the scapular plane and the deltoid and supraspinatus are optimally aligned to perform humeral abduction (53,57). In normal shoulders, the humeral head remains centered on the glenoid fossa through-out elevation in the scapular plane, with the exception of upward glide at the beginning of the movement (57)- Regardless of the plane of elevation of the humerus, the end position is the same at full elevation. The medial epicondyle faces forward and the humerus is in the plane of the scapula (28,33,64). This is the position of maximum osseoligamentous stability and greatest congruency between the articular surfaces (2833). Little or no active rotation of the humerus is permitted in this close-packed position (26,33).”

Here are the articles I glossed over:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25034959

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23141955

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3042544/pdf/nihms-256152.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24828544

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2823194/pdf/ORT-1745-3674-80-451.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2657311/pdf/JOBOJOS9120378.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2759875/pdf/nihms114886.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3010321/pdf/nihms243545.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12446161

http://ptjournal.apta.org/content/64/8/1214.long

http://www.jospt.org/doi/pdf/10.2519/jospt.1993.18.1.342

http://ptjournal.apta.org/content/66/12/1855.full.pdf+html

Derrick,

Interesting stuff – thank you!

Let me comment on that Chinese picture of the partner-assisted pain… When I was in college, we had a visiting swim coach (a Chinese national swim coach, probably no coincidence) who did that to me/us – I thought it was a dumb and dangerous ‘stretch’ then, and I still do now.

I can’t really follow the discussion in the comments – my old man eyes would require printing it all out first! I don’t have a lot to add except to say that I think the intention is what matters in the press – breaking the bar like an inverted U when benching, or a U that faces away from you when pressing overhead, or corkscrewing your hands into the ground to engage the lats when doing pushups – all of these illustrate the point pretty well, I think.

Hi Boris! Thank you for weighing in here! I highly value your views on the matter. I’ve watched your SQ Rx vids over and over; they are a first rate, invaluable resource. Thank you sir, for all the hard work that you’ve put into teaching us all.

When I look at that stretch, and also look at some of the other internal rotation activation drills, my guess is that the intent is to really groove that contracted IR position, and get the CNS comfortable going “all the way” with it. Pure speculation though.

Boris, by chance in the course of your training, have you ever experimented with an internal rotation, “screw the shoulder internally in the socket HARD, moment/action”, when performing an OHSQ, or snatch? I would be interested in your feedback if you have, or do so as a test.

I gave it a try, and I was surprised at how solid it felt; this technique flies in the face of everything that I had ever read on the matter. (Look, when the dominant OLY team on the planet is doing something, I’m at least going to give it a go, ha ha!)

Possibly different shoulder structures dictate a different rotational strategy?

RE: The purpose of supination of the shoulder is to engage the lats.

1. Can you possibly elaborate on the lat/supinated shoulder relationship? When you flex your lats hard, your shoulders internally rotate quite a lot. Does the supination set up a better length/tension relationship? (My guess.)

2. Something I never hear discussed. Let’s take an overhead lift from a rack position. Could be a press, could be a push-press, could be a jerk:

How hard do we want to engage the direct ANTAGONIST to the action that we are performing? I know that we need some antagonistic co-contraction on every loaded lift, but when going overhead, do we really want the lats firing like crazy directly against your the movement intention to lift UP, opposing your prime mover delts and upper traps?

Isn’t this a bit like “driving with the brakes on”? Maybe we want to use the lower traps for stability and tipping, and turn the lats down a bit, so the humerus can fire upwards relatively unopposed?

Just a thought…:)

Don’t know if you saw the video that I tacked on to the end of the post, but I believe that I do manage finally to achieve the suggested XR moment style press, but the IR moment press just is way more natural and effective, to me anyways.

To be clear, I’m a firm believer in whatever works as long as it doesn’t court injury.

As I said in the piece, I’ve been watching folks perform lifts differently ever since I first walked into a gym.

Pt. 2: Boris, if I could pick your brain.