Today’s guest-post is from Derrick Blanton. Derrick is a long-time lifter and reader of all sorts of fitness experts, including Tsatsouline, Rippetoe, etc.

In this post, Derrick points out a couple of important things. First, he describes his disdain for the cue “shoulder packing.” Like Derrick, I’ve never liked the term “shoulder packing.” To me, the term “pack” implies pure stability, which of course isn’t what we want from the scapulae during overhead movements. This is a semantics debate…most experts describe “packing”as a dynamic stabilization technique where the “packing” refers to the scap’s relationship onto the t-spine, however I still feel we could do better.

And second, he discusses Rippetoe’s “active shoulder” concept and suggests that folks should consider shrugging their shoulders while performing overhead movements to allow for greater upward rotation of the scapulae and reduction of stress on the tissues. I’ve never experimented with purposefully shrugging during overhead pressing – to me it sounds less stable. However, I feel that there are many similarities between the pelvis and the scapulae, and lately I’ve decided that the pelvis shouldn’t remain perfectly stable throughout hip extension. So I’m open-minded to realizing that the scapulae, in addition to upward and downward rotation, should elevate and depress during overhead lifting – it’s certainly worked for Rippetoe, one of our industry’s legends.

At any rate, once Derrick started performing his overhead movements this way, his impingement ceased. And if this provided a solution for him, it may provide a solution for you too.

That said, most of our industry’s experts feel that the scapulae should not elevate during overhead movements and should remain fairly depressed. So who is right – Blanton/Rippetoe/etc., or Cook/Jones/Liebenson/Sansolone/etc.? And if a little bit of elevation is ideal, how much? At what ranges…top or bottom? Should scapular motion be the same for overhead pressing and overhead pulling? Do we cue this or do lifters figure out their ideal form on their own? And if we should cue it, what’s the best cue? Lots of articles have been published on scapulohumeral rhythm such as THIS one, but what amount of scapular elevation during overhead lifting leads to the best “centration” of the humerus ? I look forward to reader’s comments. In addition to reading this post, be sure to read the Sansalone blog and watch the vids. Cheers! – BC

When Coaching Cues Attack! “Packing the Shoulder”

By Derrick Blanton

Oh sure, it sounds simple, and it is catchy, I’ll give you that. But “packing the shoulder” is a deceptively complex (cough, cough…malicious!) cue once you start digging a little further. Shoulder packing has morphed into two related, yet different ideas, both of which can go very wrong. #1 is the oversimplified “lock the shoulder blades down and back” version which can lead to impingement. #2 is the more technical and thought-intensive “scapular calibration” version, which can be neurologically confusing to say the least…and, uh…lead to impingement.

I’m not gonna lie, I’m a former victim of this attacking cue. I’m no longer bitter about it, although my supraspinatus is still working through its anger in counseling. I’ve managed to put my life (and my shoulders) back together and discovered a better way to cue my scaps. Maybe you might find this alternative approach helpful, too!

If I tell you to “pack” a body part while performing a resistance training movement, how do you process that information? Could you, for example, ‘pack your ankle’, and go about doing calf raises? Maybe it would be confusing for your brain to follow the instruction to stiffen the muscles of a joint, while simultaneously trying to move that same joint. Doesn’t it make more sense to think about packing a pure stabilizer (ex. “packed neck” during DL’s; “packed shoulder” during barbell curls), than working synergists directly involved in the chosen movement, like your scapulohumeral muscles in pressing and pulling?

Many lifters are still not quite sure what they are supposed to be doing with their scapulae during pull ups and overhead presses, and who can blame them? They have been given a form cue which seems to say, “Don’t move!” for a joint that paradoxically needs to move.

UNPACKED shoulder, under load and elevated on the thoracic spine. What can I say? I live for danger…

Of course it depends on how you are defining the term. Usually ‘pack’ means to isometrically brace a body part into an optimal stabilizing position, think pack your neck, or pack your abs. The common understanding of ‘pack your shoulders’ is to “keep the shoulder blades down and back”, or “suck your shoulders into their sockets”. Sounds like solid advice, right? Except that isometric bracing during loaded scapulohumeral movements can cause big time problems in the shoulder capsule.

One of my favorite strength coaches once cued pull up positioning like this: “Keep the shoulder blades down and back in the dead hang”. While this is not uncommon advice, it is potentially injurious advice. If you lock the shoulder blades down while you raise the arms upward, then your humeral heads are on a collision course with the roof of your tightly compressed AC joints. Tendons, bursa, and your supraspinatus wait helplessly to be scrunched.

When the arms are raised overhead to reach, lift, or pull down, the shoulder blades need to rotate upwards with them. The scaps are designed to roll with the arms, in a coordinated process known as scapulohumeral rhythm. Bottom line, they need to move.

I find this cue more effective: “Pull through the scaps” on the way down or back, and “push through the scaps” on the way up or forwards (bench press excepted, more on that in a bit). This activates my scapular controllers, which automatically pack at the appropriate position on the spine, relative to the load being used. No micromanagement necessary. I’m sending a dynamic signal, not an isometric one. This has enabled me to perform presses and pulls completely pain-free, with far more progressive load over time. Does this sound like a ringing endorsement for Mark Rippetoe’s “active shoulder” concept? Indeed it is!

Once I took the whole ‘shoulder packing’ notion, and tossed it in the round file, it was like taking off the parking brake, and letting my lats and delts do their work unimpeded. Heck, not just unimpeded, but powerfully assisted.

Scap-Packing Rationale

When I approached BC about exploring this shoulder packing notion, he recalled running a 2010 guest blog from Joe Sansalone which also tackled the topic:

https://bretcontreras.com/2010/05/02/guest-blog-shoulder-packing-by-joe-sansalone/

Here is another, current link from kettlebell savant, Brett Jones:

http://www.dragondoor.com/shoulder_packing_101/

First of all, kudos to both of these seasoned fitness veterans for comprehensively analyzing a highly technical thought process. I am certainly not deriding those that effectively use this technique, or coach it successfully for others. Clearly this packing notion is a useful tool for a large segment of the training population.

It just didn’t work out so great for me...

Trust me, I try to learn from everybody, and I’m sure I must have gotten the ‘shoulder packing’ idea from a Pavel Tsatsouline book, which probably explains why I spent a long, patient, dutiful, motivated, miserable time trying to use the cue. Because I really like Pavel’s stuff!

“Damn it, Pavel! Why can’t I quit you?!!” Okay, that was a little awkward. Sorry…

Both articles concur that to attempt to completely immobilize the shoulder blade, (isometric “down and back” version), would be incorrect and incomplete. Problem is that like the telephone game that school kids play, the story starts simplifying as it gets passed along.

Lifters and coaches still process it as “hold the scaps down and back”, probably because this is easier to understand than, “maintain the scapula’s position on the t-spine while it upwardly rotates”. This critical distinction between scapular positioning and scapular rotation lies at the crux of the cue’s intention, and is way too nuanced for quick CNS consumption. In actual practice, you may find yourself trying to negotiate two conflicting instructions for controlling the scapula:

1.) Maintain the scapula’s position = Don’t move! 2.) Rotate the scapula upwards = Move!

When you are lifting heavy loads, the CNS doesn’t have a great deal of tolerance for indecision. Pack becomes brace, intended nuance be damned. So the simple and abbreviated understanding of the cue lives on. But if the “upwardly rotating” part of the movement gets omitted, you may be on a one-way trip to Impingementville. I hear it’s beautiful this time of year.

I should mention that I am no expert in physical therapy or kinesiology, and I have never worked with kettlebells, which may present more technical stabilization needs. I am a traditional basic barbell and dumbbell lifter, and I pretty much do the same 6-9 money lifts along with their derivations. Here’s how I see it, having tried both active and packed shoulder styles:

● The scapulae need to actively move when arms go overhead during pull ups and overhead presses.

Not passively allowed to move, as though they are helpless passengers on the deltoid and lat bus. Rather, dynamically forced to move. If the load is heavy, it will be difficult to keep them moving. This could be understood as “shoulder packing”, or you could just think of it as “grinding out a lift”.

● The name of a cue should match the immediate understanding of its execution.

With a limited capacity for thought during movement, the directive needs to be straightforward and specific. It’s tricky to process the counter-intuitive idea of an “upwardly rotating, yet simultaneously packed scapula”. I am not so blessed with scapular proprioception that I can lock my shoulder blade up on one portion of my T-spine, and spin it from there. It does not end well at all.

(I do like when Brett Jones refers to it a “sticky” scapula. For whatever reason, that makes more sense to me.)

● Thoracic strength and extension is the literal foundation for overhead movement.

Joe and Brett Jones both address T-spine significance as well. If you are having a hard time controlling your scapulae, you are probably also having a hard time achieving strong and stable thoracic extension (always consider the next link in the chain). And that, my friends, may be the root of the problem: a misalignment due to general weakness of the entire upper back. Funny how building a powerful upper back can make scapular patterning issues just evaporate. T-spine positioning sets the angle by which the arms are going to rise, and the scaps are going to rotate. If you are firmly anchored in thoracic extension, then your scaps have a cleaner line of fire rotating upwards and downwards. If you are kyphotic, then you are screwed no matter how great your scapular control.

The Scapulae: Designed to Move with the Arms

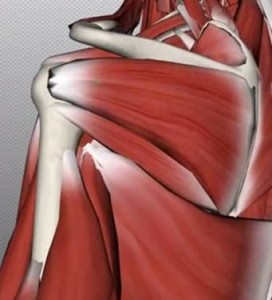

Anatomy time. (Don’t go to sleep, this will be quick.) The portion of the scapula directly over the humeral head is the acromion. That thin strip of muscle running between the two bones is the supraspinatus, part of the rotator cuff group. We want to preserve that subacromial space between the two bones, so the supraspinatus doesn’t get trapped in the middle, (along with bursa, and possibly the long head of the biceps tendon).

If you try to hold the scapula and its attached acromion down on the ribcage, as cued, while simultaneously raising the arm up, it closes up that subacromial space. Do you see the damaging, abrasive friction these opposing forces can create?

This is what happened to me as I diligently tried to keep those shoulders down and back. My supraspinatus got ground up like pink slime at the meat processing plant.

This is why the whole scapular structure needs to upwardly rotate in conjunction with the rising humerus.

Now, good shoulder packing would have you anchoring the scapula at the bottom (posteriorly tipping), and then rotating upwards from there. However, this is a very technical proprioceptive idea for the CNS to process.

Bear in mind, the muscles that directly control the scapula itself (traps, rhomboids, and serratus anterior) don’t even attach to the humeri. It’s the rotator cuff muscles, arising from the scapula that attach on the humeral head directly, and pull it snugly into the socket.

So the RC unit packs, with an assist from the lats, the T-spine extends, and the traps and serratus upwardly rotate the shoulder blade and acromion; preserving that subacromial space for the rising humerus. And let’s keep it real, here. The humeral head will be rising, at least a bit. Especially on vertical pulls, if you are challenging your lats with a decent load, the humerus IS going to rise in the socket, just like those scaps ARE going to protract when you row heavy, or pull a heavy DL, which is its own 3,500 word edition of “When Coaching Cues Attack! , Ep. 2: The Dead Lift Scapula”.

But I digress…

Why not purposefully and dynamically direct the scapular movement that needs to occur anyway? Consider the similar way the scaps and humeri also move together during horizontal movements. In a horizontal extension movement (rowing), it is sound advice to draw the arms back only as far as the scapulae can retract. Should the arm keep extending on a fixed scapula, then the humeral head will lurch into the anterior socket of the shoulder, and you are again risking impingement (this time the long head of your biceps tendon is in for a treat).

Likewise, when you do push ups or dips, your shoulder blades naturally protract around the ribcage via serratus anterior contribution. This provides synergistic force for your pecs with their direct humeral attachments, helping to pull the arm forwards.

In both cases, the scaps and humeri move in concert with each other with their parallel, but different muscular engines of movement.

We alluded to the bench press earlier. Yes, this is the exercise that really does require a no-frills, no-nuance, LEGIT PACK of the shoulders! The actual physical barrier of the bench itself prevents free scapular movement, so one should indeed “break up the team” and hold the scaps (wait for it…) DOWN AND BACK, while the humeri flex forwards. By purposely not protracting the shoulder blades, you are able to keep them wedged under the body, providing a stable base to press from.

Now, before you get too amped, packing advocates, if someone did invent a bench that would allow for scapular freedom of movement, then that would be a better bench! Just ask Dr. Squat, Fred Hatfield, who supposedly once upon a time developed just such a bench specifically to allow the shoulder blades to move. Why? Again, it is not optimal for the scaps to be fixed when the arms are moving. It is a necessary trade-off for the benefits of this exercise, but not an ideal movement pattern. This is the primary reason that the bench press has a sketchy reputation for shoulder health.

From Horizontal to Vertical

As you progress from horizontal to vertical does this normal scapulohumeral rhythm change? Put your feet in TRX straps, and start with flat push ups. Raise the straps, and do more push ups. Raise them again, and so forth, until you are doing vertical handstand push ups, partner-assisted if the load is too great. At what degree of incline did you decide that you needed to consciously focus on locking scaps down on one portion of the T-spine? It’s the same general scapulohumeral pattern, and trying to keep your scaps moving only helps you lock out the lift, at every angle. The pulling side of the equation is also the same, going from rows, gradually verticalizing to pull ups, shoulder blades and arms moving in harmony.

“But your push up example uses a closed chain movement which doesn’t require as much stabilization, Derrick!”

True, and if we had access to Fred Hatfield’s magical bench, I’d have you try it that way! But to further that logic, isn’t that one of the benefits of free weight lifting, to get so good at mobile stabilization that you are just as solid as when performing machine, or closed chain moves?

The Push to Put Upper Traps Back on the Ballot

I’m going to again go off the reservation: Upward scapular rotation (movement!), works even better when you throw in some good old fashioned elevation. Also known as shrugging. (Note: this is about the point that I feared BC was going to shut down the guest blog visa program…) Here’s what that looks like:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2aVCxz-j4Ck

The upper traps provide powerful force to help raise the arms overhead, particularly as the load gets heavier. Last summer I did the Tough Mudder mountain obstacle run. Part of the team oriented event involved helping female participants scale the 12-ft. walls, essentially overhead pressing them to the top. After running up a mountain for two hours, with my heart rate stuck at 160, I wasn’t thinking about “path of instantaneous center of rotation”, or whether my scapula was “maintaining its position on my thoracic spine as it rotated upwards”.

If I had a thought at all it was, “UP!!” Basically, I was just overhead shrugging trying to get these ladies over a wall!

I’m sorry, did I just say something controversial? I used my upper traps as active synergists with my delts and triceps to complete the lifts by shrugging. Furthermore, this was functional unstable load training literally personified, balancing and lifting human beings by their feet wobbling in my hands. Somehow my scaps managed to naturally pack themselves along the way up the T-spine.

I gather that this is considered a dubious technique in the packing world.

“Most people have upper trap dominance issues and upon pressing overhead the force couple is not happening or out of sequence, and in order to get the arm overhead they inappropriately shrug and elevate the scapula and humerous into the Acromium causing impingement of the sub-acromial space.”

Suppose you have balanced upper and lower trap strength…shrugging goes back on the approved list? Your upper traps are very powerful players, and their primary function is scapular elevation. It’s what they were literally created to do. Don’t make them stand by and hold a clipboard. Put ‘em in the game, Coach!

If your upper traps are disproportionately strong, then bring up the lower traps! Focus training energy on T-spine extension, and lower trap strength. I love this Diesel Crew two-minute shoulder warm up as a building block to controlled, heavy shrugging rows:

Major props to Jim Smith! The best prehab/rehab patterning routine I’ve ever seen, because it teaches you to activate the scapular controllers as a precursor to moving the arms. The drills in Joe’s post are terrific, too, especially for establishing scapular MMC’s (mind muscle connections).

Seated upper back good morning, one of many techniques to strengthen the thoracic spinal extensors. Activations and mobility drills are excellent and necessary, but at some point you have to progressively LOAD the T-spine.

Dangerous Dead Hang?

Here’s that unpacked shoulder again, this time in the dead hang bottom position of a pull up. Shoulder blades are elevated, and upwardly rotated.

Almost universally this is considered bad, risky form.

And yet this is the best approach I have found for keeping my acromion off my humeral head. Actively shrugging the upper traps, while maintaining isometric lat tension. No hanging by tendons.

“Keep your shoulders off your ears, bro…”

But that would require me to rotate my scaps down, and-

”Right! Pack ‘em bro…Down and back..”

I promise that I will pack them nice and tight when I get up to the bar…

“Pack ‘em in the hang, too, bro…”

Agree to disagree?

I’m not anti-packing! I’m a big fan of packing your abs and glutes to set your T-spine in extension…

Chapter 947: Rotator Cuff Tension and the Mobile Scapula

“Remember, the rotator cuff can’t build proper tension and properly stabilize the humerus if the scapula is moving around on the t-spine as it attempts to upwardly rotate.”

Seems to me that RC function on a moving scapula is a trained variable, like all other aspects of strength training. This again calls to mind when someone switches from doing exclusively machine resistance training, and switches to free weights. Yes, at first, it is more dangerous as they are wobbly, and learning to stabilize the floating weight. But as they groove the movement with practice, it becomes safe and effective. If you are not used to a “floating hip” scapula, or if you have awful thoracic spine strength, then certainly you might be loading the RC in a dicey position. Once you have the appropriate yoke and T-spine strength, your RC should function fine on moving scapula. For example, performing a barbell overhead shrug, or climbing a rope.

I actually think that grip intensity correlates with rotator cuff function, more than scapular movement on the T-spine. Clench your hand tightly, and your shoulder seems to pack itself. Your humeral head tightens in the socket, and your CNS understands that the shoulder better be ready for business.

Try hanging from a bar by one hand while squeezing as tightly as possible. Shrug and move your shoulder blade in all directions while still tightly clenching the bar. Your shoulder will feel stable and connected as one long organized beam until your grip begins to fail. For you martial artists out there, throw a snapping punch with a clenched fist, and then again with an open hand. Which one did your shoulder like better?

That’s a wrap!

Folks, this article got entirely out of hand! Who the heck writes 3400 words on an obscure coaching cue? Everybody who plowed through this whole post will receive a complimentary participation medal. (Just e-mail Bret for delivery instructions.)

Clearly I’m laying out a subjective perspective, as proprioception and MMC’s are highly specific to each individual. If you are able to use the ‘pack the shoulder’ cues safely and effectively, more power to you. Ultimately, we all have to find our own processes on this journey, whether it’s BC allowing thoracic flexion to get 140 more pounds on his dead lift, or DB turning his scaps loose to press and pull without pain.

I wish you all very productive training, and remember to take your powerful nutrient repartitioning agents, because an empty pump is a useless pump! (That was just…so….unnecessary…)

Thanks for reading!

Good morning,

You’ve done a great job hitting a nail on the head in discussing scapular movement and why such movement is necessary for proper shoulder function and health. Like you, I used to work really hard on keeping that scapula down & back while pressing and doing pull-ups. My result was the same as yours: pain. And basically it felt very awkward. Now I think of the scapula as sort of a backstop to the humeral head. The scap and humerus should move together. If one part stops then the other part needs to stop too.

Further, I’ve gotten into Shirley Sahrmann’s work. To your point about “most people having upper trap dominance,” She suggests otherwise. That in fact a whole lot of people have very UNDER ACTIVE UPPER TRAPS. I’ve seen evidence of this with a lot of clients. Once they’re cued to move the scapula upwards during an overhead reach or press, their shoulders often feel a lot better. The Sahrmann wall slide exercise is effective in getting the upper traps to do their share of the work.

Thanks,

Kyle Norman

Thanks Kyle! Appreciate the input from Sahrmann.

Thanks, Kyle! Kindred spirits..

To be clear, that upper trap quote was from Joe Sansalone’s piece, sorry that was not made clear, my bad. I’ve seen that “upper trap dominance” concern on more than a few other resources as well.

I could not speak to the relative trap dominances of the world’s lifters, but I do think for me personally my ENTIRE trapezius, upper, lower, and all parts in between was straight up, too darn weak.

I do think it is a mistake to think about subtracting a strong muscle to work around a weak one. Make the weak one strong! Find it, activate it, load it, and crush it with volume. What was your weakness will become your strength!

Great Article – interesting timing since Mike Robertson also has an article on shoulder stability published right now too.

I think that packing the shoulder down and back comes from the fact that at the end of scapulohumeral rhythm the scapulae actually depresses as the arm completes flexion (check Sahrmann or any other source on the biomechanics of scapulohumeral rhythm). You are right that during the first 170 degrees of overhead motion the scapulae elevate and upwardly rotate.

If you or a client has good body awareness, you should be able to pack your shoulder from a dead hang position on a pull up bar by depressing the medial scapular border with low trap, providing increased scapular upward rotation and posterior tilt of the scapulae. The picture you show above shows packing the scapulae with the lats, not the upward rotating low trap. The same thing applies with an overhead press, if you can emphasize increased scapular upward rotation and posterior tilt, then you can have an even more stable scapula position without any GH joint impingement.

The scapulae are definitely designed to move , but there is always an idea position for them to move to, shrugging with upper trap is good, shrugging with levator scap is bad.

Thanks for the great post

Thanks Jason!

Jason, great points, and sorry I replied to you down below…Must improve my comment posting skills..:(

Nice read!

In my opinion, the “show your armpit forward” cue, which is kind of famous for overhead squatting, is pretty cool.

It implies both scapula and shoulder joints movement/position.

It also feels good for press. I haven’t tried for pullups yet.

Good call Frankwa.

Great insights, Jason.

Haven’t seen Mike’s piece, but I will definitely check it out. Eric Cressey recently got into some of this as well. In fact, since I first sent the outline for this piece to BC, I’ve seen at least 5-different articles on various blogs and websites all relating to overhead mechanics, and all posting in the last few months. Which sort of reflects the ongoing confusion that still exists for training public.

Yes packing the shoulder in the dead hang with lower traps is doable. In practice, it never painlessly happened for me, though. Goodness knows, I spend hours on park pull up bars trying to do just that. At some point, if trains and cars keep colliding, it’s time to change the stoplight pattern.

I actually cut out a portion of this overly long winded article where I discussed the disconnect between the brilliance of the PT and kinesiology cognoscenti, and the trainers trying to simply move with a brain full of theory. Paralysis by analysis.

I have come to believe that there are different types of people that relate to their own movement in different ways. I am a classic ‘over-stabilizer’, which means I have many muscle groups which want to fire together, they tend to overdo it, and I lock up. For me the goal is more fluidity in my movement. I realize that there are others that tend to more sloppiness, and just need to get tighter.

If someone can selectively fire their lower trap fibers in an isometric stabilization fashion, while still rolling their scaps enough to preserve subacromial space, then as stated, props, and do it.

I just couldn’t figure out how to make it happen. Thanks so much for reading and discussing!

I commend you Derrick for working with me on this. I nitpicked you to death haha! After all the revisions, I feel it was greatly improved upon. I appreciate the thought-provoking stuff, BC

Well if by “nitpicked”, you mean challenged me to do better, than I’ll take that nitpicking every day of the week, and twice on Sunday, BC…

Hopefully everyone realizes how passionate and generous BC is with his time and energy… That’s why this blog rocks the house!

Awesome article, Derrick! I agree about the bench press, quite a dysfunctional movement pattern. Also, I was reminded of this great article:

http://robertsontrainingsystems.blogspot.com/2007/09/push-ups-face-pulls-and-shrugs.html

Regular shrugs seem to be a problem as they can’t balance upward and downward rotation strength, since they target the upper traps but also bring in the rhomboids and levator scapulae.

I agree that there should be scapular elevation and depression, as well as upward and downward rotation during vertical pushing and pulling, but I think it should be moderate, as the scaps should remain relatively stable. During overhead presing, posterior tilt of the scapula is important too as you mentioned, and good thoracic extension is indeed vitally important. I also think that creating an external rotation moment (trying to break the bar in front of you) can help.

Thanks Sven! Another good call regarding the external rotation moment (along with Frankwa’s post).

Sven thanks so much, and I’m glad you liked the piece.

What I’m suggesting is that the LOAD will moderate the degree of scapular elevation and depression, it’s not something that really requires conscious micromanagement. When I lift, it is all systems go, UP! My scap never outruns my arm. Never.

Will this approach work for everyone? Dunno…Does any approach work for everyone?

Funny that you brought up the breaking the bar cue. That would almost be my next “coaching cue attacking” article, ha ha… (I’m beginning to realize how differently I process these movement cues than normal lifters.)

When I try to break the bar, I process it as a literal external cue, and torque my elbows too far in relation to the bar. This is not good, as your elbows should move to align directly with the bar, particularly on any straight bar movement, this includes straight bar pull ups. (This is why chin ups can start wrecking peoples medial epicondyle).

I’ve almost evolved to an “Arnold press” approach, but with barbell. Externally torqued hard at the bottom, but with an unfolding spiral internal rotation as the bar elevates. I think you can see this happening on the pressing video from the piece.

Anyways, great feedback, and I will check out those Robertson links…Getting a lot of Mike Roberson love up in here, and rightly so, he’s a genius.

Thank you both. I see what you mean, Derrick, about overdoing the external rotation moment thing and stresing the elbows, and I have experienced it, but I thought using the “show your armpits” cue towards lockout worked pretty well…i.e. I’m probably increasing the external rotation moment towards the completion of the press. Do you think that’s wrong, then? In keeping with Kit Laughlin’s point, it feels right in the body so far…

Sorry, the article I wanted to link is actually:

http://robertsontrainingsystems.com/blog/push-ups-face-pulls-and-shrugs/

Great article, love the depth of thought and discussion.

To achieve optimal overhead kinematics, the scapulothoracic and glenohumeral joints have to work synergistically. As an example, the old recommendation to “squeeze your shoulder blades” together during shoulder work is probably outdated. You don’t want to retract your shoulders and hold your scapula in this position while elevating your arm. This reduces scapulothoracic movement and produces a dysfunctional overhead movement pattern. You need to upwardly rotate, posteriorly tilt and protract your scapula.

This is probably similar to shoulder packing. You may not want to isometrically hold your scap in place while performing any arm movement.

I believe the rationale for both of these cues is to attempt to reduce upper trap contribution in favor of lower trap. This ratio is important to proper movement patterns of the shoulder and has been shown to correlate to pathology.

The problem with shrugging before a movement is individual variations. Realistically, either variation can likely be performed with good results in the right persion. If the person you are working with has poor rotator cuff function or limited glenohumeral mobility, the shrugging motion could feed into superior humeral head migration and potential pathology. Shoulder packing wouldn’t do this as much, however may not be the answer as well.

It probably comes down to the simple fact that there is no one way to skin a cat. The best programming involves proper assessment of the individual in front of you. Select the technique that is most applicable for that person for the best results. I do agree with the discussions, we sometimes get caught up on what is “hot” on the internet instead of relying on proper assessment.

Thanks for sharing, great article.

Mike

Hi Mike, thanks for commenting! Have you seen any research in regards to humeral tracking in the glenoid during overhead movement? I’m wondering how we “know” what leads to the best centration. Has this been examined, or is it just speculation?

I’ve read up on upper trap dominance, but assuming good UT, LT, and SA force coupling (or tripling for that matter), I wonder how scapular elevation impacts the other variables (upward rotation, posterior tilting, and protraction) along with humeral migration. You suggest that it could lead to superior migration and pathology, but I wonder if this is conjecture from folks with weak lower traps who didn’t have proper “tug of war” going on in different directions and therefore may not apply.

Thanks again for posting – you’re the man when it comes to the shoulder joint so your input is appreciated!

Mike,

I agree with your thoughts. Some others to consider:

1. When someone has a scapular dyskinesis due to muscle imbalances (i.e. poor lower trap, serratus, rotator cuff strength, etc…), neurological timing, etc. why would a coach ever instruct an athlete to lift overhead prior to correcting the problem(s) at hand?

2. Specific overhead exercise performance will play a role in the possible risk of shoulder pathology. Is the exercise performed overhead in the plane of the scapula where the utilization of a barbell as well as the proper grip distance upon the barbell during an overhead press will ensure a pathway throughout this scapula plane, or is a dumbbell press or behind the neck press utilized which will emphasis the bar path in the coronal plane (abduction) of the body?

3. To date I personally have not found the need for “packing the shoulder” (as I understand it) with the performance of (arms) overhead exercises. With “suitable” glenohumeral-scapulothoracic “rhythm” along with proper exercise instruction and performance “form will follow function” and the body will take likely care of itself throughout the exercise performance. I don’t like to argue with mother nature.

4. Arguably the strongest and most powerful athletes in the world, weightlifters and track and field throwers lift overhead and the instruction of “packing the shoulder” is not included, to my knowledge, in their training. In my 30+ years of (overhead) rehab and training of athletes “packing of the shoulder” was not heard of or utilized until recently. Yet through the decades without “packing the shoulder” I personally have experienced infrequent incidences of shoulder pathologies that occurred during overhead exercises when utilized appropriately and with the appropriate athlete. Athletes have successfully lifted overhead without “packing the shoulder” for a very long time.

5. I am of the opinion that excessive exercise volume is the major culprit for inducing shoulder pathology, as fatigue will change scapula and gleno-humeral neuromuscular mechanisms, mechanics and position. Therefore overhead exercise volume is critical to the athlete’s programming.

6. Of all of the conversations I have witnessed re: “packing the shoulder” the upper and lower traps are usually the main topic of discussion. I have yet to hear the role of packing the shoulder with the arms overhead and the effect of the latissimus dorsi muscle upon the gleno-humeral joint. It is very difficult to have one’s arms overhead and then isolate the lower traps via “packing the shoulder”, holding a load, without including the involvement of the lats. We must remember that a muscle has both an origin and insertion and the contraction of that muscle may have an effect at both attachments. Since the lats are a very strong muscle group and attach to the humerous (i.e. performing adduction and internal rotation), if fired along with the lower traps in a “packing” fashion with the arms overhead (where the requirement of overhead movement is more plane of scapula/abduction and external rotation), what effect does that have on the humeral head and it’s position in the center of the glenoid?

7. Glenohumeral-scapulothoracic (GH-ST)“rhythm” ratios change dependent upon the environment of the shoulder. GH-ST shoulder “rhythms” vary when comparing passive overhead motion to active overhead motion to HEAVY LOADED overhead motion. McQuade and Smidt have demonstrated that during heavy load elevation this GH-ST rhythm increases to 4.5 to 1. This makes sense as the moment arm from the weighted bar increases as the bar continues overhead, thus a greater amount of scapula stability is required for the GH joint to support the load and the lift to be successful. Why then would we want to further reduce/change the position of the scapula during heavy overhead exercise performance by packing the shoulder? This is another reason why proper overhead volume programming is so important.

Just my opinion

Great stuff Rob!!! As always I appreciate your comments. I tried finding the article you referred to when we spoke, to no avail. Glad to see you found it. In case readers want to pull up the McQuade and Smidt article, here’s a link to the full paper:

http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=2&ved=0CCcQFjAB&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.jospt.org%2Fmembers%2Fgetfile.asp%3Fid%3D796&ei=Zm1JUKTOO_OLyAHZnIDYBQ&usg=AFQjCNH3D9mOVfU2G-RsN0gTVftoDFYqbg&sig2=DtRrqvYO_B0TwSAhLj8C9Q

Not sure if it will work…worked for me though.

Mike, you have probably forgotten more than I will ever know about this stuff, so huge respect, and thanks for dropping some knowledge. I like what you are saying that this is not a one size fits all process, and calls out for individual assessment.

If the rationale is in fact to work around weak or inactive low/mid traps, then this strikes me as trying to “back into a solution” rather than attacking the problem head on, which I alluded to in the post.

Instead of creating a whole new awkward CNS movement pattern, complete with cues that have demonstrably shown to be problematic for sizable segments of the training populations, let’s instead find the weak link, and militantly go after it.

So Client Weak Lower Traps, here’s your new protocol for the next two weeks:

1. No loaded overhead work.

2. Diesel Crew warmup, twice a day every day, progressive loading.

3. T-Spine mobility drills, twice a day every day.

4. Ultra-controlled shrugging barbell, V-bar, or plate held rows, twice a day every day, progressive loading.

5. Ab and glute work every day.

After two weeks, overhead medicine ball throws, segue into light dumbbell overhead presses, segue into barbell overhead presses.. Test/ retest. Don’t have the mid back foundation, yet? Back to step 1.

This strikes me as better than, “Oh your upper traps are too strong and dominant, let’s teach you not to use them, and maybe we can downgrade them to your weak lower traps level…”

(I actually just glanced at Rob’s post below, and seems like we might be on the same page here…) Anyways, thanks again for your input, it is an honor. 🙂

Derrick,

At this time, as you probably can devise, I am certainly not an advocate of packing the shoulder during overhead exercise performance and some of my reasons have already been posted. However, there are intelligent and successful professionals who do advocate the packing of the shoulder technique with reasons of their own. Each philosophy may be different yet still effective for the particular professional incorporating their particular philosophy. Be careful not to get trapped in the “right vs. wrong” scenario. I post my reasons for not packing the shoulder during overhead exercise performance to “level the playing field” in an attempt so a young coach may make an “educated decision”, whatever that decision may be. I’m at a point in my career where frankly, I could care less if anyone “does as I do”. Various coaches utilize different techniques successfully as there is no “best” training program or else we would all be doing the same thing wouldn’t we? Mike provides us with some very good advice as there is more than one way to skin a cat.

I would also suggest that your training philosophy be based on both scientific (fact) and empirical (experience) evidence. I would also heed to Mike’s advice to rely on a proper assessment and address the specific information provided by that assessment. Don’t get caught up in the “hot topic” of the internet and try to apply everything under the blanket of that hot topic.

Great topic, thanks for posting

Thank you, Rob. Your perspective is very thoughtful and wise.

Sometimes thinking out loud in print reads as inappropriately declarative, not my intention (as opposed to sitting around the gym or coffee shop and having a free flowing exchange of ideas.)

Apologies for not being more circumspect.

Derrick,

If you wouldn’t mind could you please send me your e-mail to me (RPanariello@professionalpt.com)

Hope all is well.

Rob

I’ve thought about this too; if low traps are weak, bring them up via prone trap raises, etc., but don’t completely abandon all exercises that work the upper traps.

Hey Bret,

I’m commenting here after just reading the intro to your article. Going to read the rest but don’t have time today.

I have a little bit of impingement going on in my left shoulder. I’ve been pushing my training a little harder lately and although I’ve been stretching and doing everything I know to keep the scapular moving properly to avoid it.. it’s here.

I was surprised about the idea to shrug up when overhead pressing, and here’s what I can say about my experience.

Right now, if I put either or both arms over head and “pack” everything down, I feel no discomfort in my left shoulder. But the moment I shrug upwards with my arms in the overhead position, I feel pain in the subacromial space.

My “impingement” is very new without much inflammation I suspect as the pain is very quick on/off with movement and doesn’t linger.

So I’ll be going carefully with pressing movements for a while.

My next upper body workout is Friday, so I’m definitely anxious to get into the meat and potatoes of this article.. it looks AWESOME!

Thanks again!

From Canada!

Good to hear Shane! I appreciate the input. Of course I’m no physical therapist and I believe strongly in letting pain be your guide. So stick to what works for you. – BC

Very interesting article, thanks!

I’ve got this exact dilemma myself (Rip coaches shrug at the top of press, Pavel and other KB guys coach “packed shoulder”).

Fortunately, there is Dan John, who was able to explain “packed shoulder” better than anybody else. Here is quote:

“Grab the tag on your shirt for me, you know, the one on the back of your collar. For most guys, Welcome to the Packed Shoulder! Now, many will have to slide down the spine a bit more to get the position, but this simple movement “instantly” gives the packed shoulder.”

You can read entire article here:

http://danjohn.net/2011/11/teaching-or-learning-the-kettlebell-snatch/

Then I compared this position with what I achieve when I “shrug” my shoulders at the top of the BB press (note: the shrug, according to Rip, should occur as the very last thing, it’s the finish of the press). You know what? For me it’s exactly the same position! The bar does not allow you to move your arms too close together, and the load does not allow you to elevate shoulders too high.

On the other hand, if they were teaching “shrug” with KBs, I’m sure I’d end-up with too elevated shoulder and probably my biceps behind my head.

As for pull-ups, you know what is the first exercise every gymnast learns on the bar or rings? Yes, it’s complete dead hang, bicepses on ears. Note that they also get to this position on every big turn, and even on 1 hand, where overload is huge. They should know a thing or two about it, right? So the advice not doing it was always a mystery to me.

Good stuff Sergei! Appreciate the comment.

Fantastic article, Derrick. For some reason, it made me think of something George Costanza once said: “It all became very clear to me sitting out there today, that every decision I’ve ever made in my entire life has been wrong.”

Ha ha! Perfect…just perfect, Chris. You just made my day. I’m going to be laughing the rest of the day.

Thanks so much for the kind words..

In all overhead work, we always try to press the arms and shoulders as far off the body as possible, for all the reasons given here. If the shoulder girdle cannot move up and back on the ribcage, then acromium–humerus impingement is likely. The cue that gymnasts use (when doing all their handstand work, both statically and dynamically, very high loads indeed) is try to press the shoulders (delts) against your ears—the exact opposite of packing.

I believe that the body will tell you clearly, and in no uncertain terms, when what you are directing it to do is not working for it. When I first heard the “pack the shoulders” cue, I tried it; and it did not feel right in the body—so I dropped it.

In my experience THE key to shoulder health in all overhead work is sufficient thoracic extension, and sufficient shoulder mobility under load—so the body’s strength can be perfectly aligned under the task. I have a YT clip on my channel that shows my main guy doing a Turkish getup with a 48Kg Kettlebell, at a bodyweight of 70Kg. he has since done the 56. Look at his alignment: perfect. See the clip here:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A8GdWEViPPg

As well, the other key to shoulder health it to get the ration of internal to external rotator cuff strength closer to 1:1. In my experience, it is closer to 2:1 (except in rock climbers and gymnasts). For most gym-based trainers, this means strengthening external rotation at as many angles as you can, and in the anatomical position (both teres minor and infraspinatus contribute to this action roughly equally and the shoulder joint is in its strongest position). There’s more, but “packing the shoulders” was always poor advice, except when doing pushups (completely different plane of movement). For overhead, “press the arms as far off the body as you can” works.

Yes, gymnasts do that, but HSPU are a closed kinetic chain exercise. Is it applicable to the more unstable environment of the press? As an analogy, active scapular protraction is encouraged during push ups but not during bench pressing, right?

While it’s not normally taught, there are people that do bench press shrugs or bench press plus a shrug in the similar manner as the push-up plus exercise. When I powerlifted I did this as an accessory exercise and it added to shoulder/scapular stability and health. I know Christian Thibadeau also teaches the active shrugging on overhead pressing. Personally, I think both styles can work because they increase the activity of the synergists (primarily the lat on packing and the trap on shrugging), but I’m partial to letting the ST joint move with the GH joint because it makes sense, it works for me, and it’s worked well for my clients.

Thank you, Rich. I just checked Thibaudeau’s recent cues, and found this:

http://www.t-nation.com/strength-training-topics/1767

“4. Do plenty of overhead work, and on every repetition focus on getting into the perfect overhead hold position (shoulder blades together, show the armpits) and hold it for a second or two. ”

So, he’s advocating that external rotation moment, but also retraction, not protraction…and not a word about exaggerating scapular elevation. I’m a bit confused now!

Sven, I relate to your confusion. At some point, you’ve used up all your cue privileges, and you must start going to “the back of the brain”, and just start moving.

As they say, “The mind is a terrible thing..” (well they actually add “to waste..”, maybe I just shortened it..ha ha..)

If you are locking up with indecision, perhaps find some video that represents the form that you desire, and start trying to emulate it. And film your attempts, and IMMEDIATELY review them, and go again…(light loads, please)

This is from BC’s bag of tricks, and it is a hugely effective way of bypassing this joint by joint attentional focus, which can be a bit overwhelming..

Best of luck!

Thanks Sven! I had read his recommendations in May of 2011 and he always aid to shrug as high as you can at the top. Confusing indeed…agree w/Derrick’s re:

Bret, is there an edit function on this interface? If not, please change “delta” to “delts” plesae (damn auto correction).

Fixed it Kit. Thanks for your input, as always!

Great article Derrick! Shoulder packing felt wrong for me from day 1, close a decade ago the first time I heard Pavel coach it. I know gymnasts activey shrug in the overhead position and that felt much better when practicing 1 arm handstands. Using a shoulder pack on these felt lazy and put a ton of pressure in my joint, whereas shrugging just felt exhausting to the musculature and likely the connective tissues. I just played with Mike’s cues of posterior tilt and using protraction as opposed to elevation and its the best my upper body ever felt on a press…now to figure out if it’s applicable to handstands.

On a side note, I’ve had my own gym for 10 years and just started PT school. It’s required for us to research in our second year, so if anyone has a specific investigation they’d like me to make on overhead press biomechanics I’m open to try and expand the data on this debate.

Rich, thanks! Sounds like we had a pretty similar experience with this one. PT school sounds exciting. From a personal standpoint, this shoulder issue is settled for me, but this lumbar fascia support theory would be incredibly interesting to hear more about:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B-SMUA3QfVw&feature=player_embedded

There are two more vids on his home YT page. I watched all three, and they are so counter-intuitive, yet so strangely “right” that I can’t get the ideas out of my head…

I don’t know about Gracovetsky’s speech…

I skimmed this article http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20709320

and printed it out. Will give it a closer read but it appears that the TLF doesn’t lead to much of an extension moment. I’ve read studies by Gracovetsky (The Optimum Spine I believe) which showed huge contribution from the TLF, but McGill has refuted this as well (see references 3 and 4 from this link: http://physicaltherapyjournal.com/content/70/6/394.full.pdf)

So all in all, I think it’s overrated.

I am all for armpits forward, active shoulder, the press never ends. I have been playing with a behind the neck press as a ” balancing” exercise with the bench in a Wendler program. BTN pressing gets a bad rep on most things I have read. I feel as though the movement is safe if the press can be executed with correct humero- scapular- thoracic mechanics and without and movement of the head. I am certainly keen to hear other perspectives.

Yup, Brett, I also like to press behind the neck just to make sure that external rotation ROM is available to me. Many moons ago, used to do it more or less exclusively, (this was before the internet, and all that fancy “book learnin'”) now just feels good for a change of pace. Helps on SQ day. It is probably riskier, depending on XR ROM. Seems to hit the upper traps very hard…

I like it because of the superior muscle activation, but I do not feel that most people should do it.

Keeping the arms in the scapular plane (as Rob P has pointed out) is much safer.

First we get Contreras telling us that a woman he coached had only 10% activation of her glutes during a heavy below parallel squat (how one extends the hips without use of the hip extensors is a mystery which only Contreras has ever solved).

Now we have Blanton telling us that “shoulders down and back” leads to supraspinatus impingement. Really? In how many people? How did this interact with the very common issue of protracted shoulderblades and internally rotated shoulders, which has been clinically shown to contribute to impingement?

In the former case questioning of this was responded to with “oh I have proof… maybe later.” I suspect we’ll get a similar response here.

It’s alright if you’ve found some cues or little tweaks work better than others. But be careful with these sorts of claims.

Kyle, where to begin?

Shoulders down and back is a good postural habit. I am referring to shoulders down and back during the performance of specific overhead movements, and I am referring specifically to my own direct experience. I am not making blanket scientific claims regarding shoulders everywhere.

When I attempted to hold my scapula down and back on my ribcage while performing overhead movements, my supraspinati were injured. This went on for close to a year as I tried to understand what was happening. When I researched the problem, I realized that I was far from alone in this experience.

As far as how many others across the world ever have experienced this problem, of course this is an impossible question to answer. I can tell you if you start searching around, you will find others who have had the same problem. You can begin your search with a few on this comment board.

Lastly, protracted, internally rotated shoulders would definitely contribute to impingement, as would a kyphotic upper back, as does a hooked acromion. We are in agreement there. I didn’t write a wholly inclusive essay on every single risk factor for shoulder impingement.

Hi Derrick

Love the article and discussion coming out of it.

I would even question whether “shoulders back and down” is even that good a postural habit/cue. Here’s a another quick take on that idea – http://www.cef.co.nz/articles/58

For me there is an important distinction between ‘stabilizing’ and ‘fixating’. I speculate that taking any cue to into fixation is bound(sic) to lead to problems.

Oli, you rock!

I really like where you are going with this! I’m going to make a slight distinction, though..I think there are cases where absolute lockdown fixation helps activate prime movers.

For example: Pack those shoulders on a barbell curl. You are only going to increase biceps activation with completely locked down scapula. In this exercise, the scaps provide no force to move the bar. You could I guess shrug to get it moving, but really it’s the elbow flexors that must perform. A completely tight scapula will help the elbow flexors go nuts..

Bench pressing..FIXATE the spine, the hips, yes the scaps, see the post (although quick aside, I realize that I still try to move my scaps when I bench, still! I can’t help myself..)

Turn the entire body into concrete, and let your pecs, delts, and tris go nuts. Can you bench more locked down, or with your feet in the air? Stability enhances CNS flow to agonists. Generally the more stable you are, the more the CNS just turns on the juice. There is no need to protect the body from falling, wobbling, etc.

Tightly braced abs and glutes will help your pull ups and OHPR’s, etc..

Some pretty good strength coach once wrote that “maximum stability promotes maximum activation”, paraphrase…hmm what was that guy’s name..can’t think..Bret something..any hoo…This is why, usually we are stronger on machines because they do the stabilizing for us, and our prime movers can just go absolutely nuts with no balance requirements.

To get back on point. FIXATE vs. STABILIZE during shoulder packing: Maybe it’s because I have a very literal mind, I can’t seem to get my CNS to cooperate with the idea “pack while moving”. It is a comical failure on so many levels.

Again, I have found it to be an utterly irrelevant concept, once the T-spine is cast iron extended, and the glutes and abs have you anchored like steel beam… and the entire trapezius is powerfully, dynamically activated. I’m beating the hell out of this same point, but I can’t tell you how much better it feels to not rely on the scap for stability, but rely on the T-spine, and glutes and abs. People are not realizing how powerful an unleashed, active, dynamic trapezius can be, moving up and down.

Your goal when overhead pressing is to THROW THE BAR THROUGH THE CEILING!

Your goal when doing a pull up is to TEAR THAT BAR OFF THE FRAME!

WHY AM I WRITING IN ALL CAPS? sorry..

In order to achieve this goal you are going to need your traps to be MOVERS (stop with the caps!!) and shakers..

HOWEVER (grrr..)…

If this post is a rambling mess of thoughts I apologize…we had an earthquake while I was writing it… (so you’re using that old earthquake excuse again…)

good point -I just kind of wrote the fixation idea off the cuff and it’s good fun to tease it out a bit.

In those examples the ‘lockdown’ isn’t in end range(?) aren’t they examples of a dynamic co-contraction? would that co-contraction be able to generate more force if you could -if required choose to move explosively out of it as needed?

eg: Having feet on the ground in bench-press enhances your bench but HOW could they push into the floor?

If they were pushing into the floor in such a way that if required they could explode BANG off the floor in a second would they be generating more force up and through your spine and be more stable then locked down driving 100% through the floor and ‘away’ from your spine? -I think so (although again pure speculation and of course to actually lift your legs while benching is not my suggestion -but that they are ready to do so).

I get that this is getting away from the difference between letting your scaps elevate and protract compared to keeping your spine stable but I think it’s an interesting idea.

I don’t think a human being is designed to stabilize in the same way as a piece of gym equipment or a floor but to transfer force from said surface (excuse any violations of the laws of physics).

As upright bipeds our stability (and balance) in standing doesn’t come from rigidity -how could that become the case in a standing shoulder press where we raise our centre of mass so much higher?

Hope that makes sense. I’m raving now too. I appreciate your response and passion, consider all these points on the table for discussion as it’s all conjecture on my part.

I have met my nemesis…and his name is Oli.

Nemesis, er, Oli..there is something persuasive here..:) There’s something right, and there’s something wrong with what you are saying. Let me think about it a bit. Right now my brain is exploding with electrical activity like that last scene in “Carrie”.

Well played.

(Off the top of my head, though…To explode out of any postion requires you to IMMEDIATELY release the antagonists, and open up the floodgates in the opposing direction. Also explosive movement is so enhanced by a violent stretch reflex…)

When I relate it back to the topic du jour, yes I am hitching (pre-stretching, trying to generate a mini-stretch reflex) ever so slightly with scaps in the opposite direction prior to explosively firing up or down depending on which exrcs. I’m doing.

But I think from mid-lumbar down (GLUTES!) the more solidly locked, the better…unless I’m push-pressing of course..(brain explodes)

Hmmm..

When speaking of bench pressing and overhead pressing we are speaking of 2 different animals. As we achieve a weight loaded increased overhead range of motion the GH-ST rhythm/timing and scapular stability vary (as already stated) and become more critical in successful exercise performance. As the arms extend overhead, an increased (and weighted) moment arm is established maximizing as the arms fully extended.

We don’t want “fixation” of any joint as we do require a necessary mobile yet “stabilized” scapula throughout this ROM as that is the requirement to present with a stable platform to allow for efficient mobility of the GH joint. If one would not think a stable platform (proximal stability) is necessary for efficient and controlled (distal) mobility try shooting cannon out of a canoe.

The GH-ST rhythm is critical for the proper positioning of the glenoid as the arms elevate overhead to ensure the proper centering position of the humeral head in the glenoid. If an individual presents without any strength, neuromuscular timing, GH-ST deficits or dysfunction, etc… why is it necessary to change the normal overhead biomechanics of the body by “packing the shoulder”? Why do we want to fool with Mother Nature? As I stated earlier in this posted article, with an appropriate athlete under appropriate conditions, as with ANY exercise performance, not just the overhead press type exercise, wouldn’t “form follow function” and the amazing machine called the human body take care of the “details” until we as coaches via inappropriate coaching cues, programming errors, etc… disrupt this natural system of efficiency? If anatomical, biomechanical, etc… abnormalities or dysfunctions are present, why would we ever have the athlete lift or perform work overhead and place them at increased risk of injury prior to correcting these issues?

As far as the bench press is concerned the scapula are retracted during exercise performance so that the body has a platform (foundation) from which to push from. Fixation of the scapular also occurs “artificially” so to speak as the “pinning” of the scapula between the bench surface and body weight in addition to the bar weight creates high scapula thoracic compressive forces. Compression forces enhance joint stability and thus with this contribution of “artificial” scapula stabilization (fixation) the musculature of the scapula are not required to work as intensely or with as much efficiency when compared to an overhead exercise performance.

The last factor with regard to the comparison of these 2 exercises is that during the bench press performance, arm elevation (overhead range of motion) is not nearly that of the overhead press type exercise performance and therefore does not require the same necessary anatomical and biomechanical contributions and efficiencies of an exercise performance concluding with the arms fully extended overhead.

Just my opinion

Kyle, you should show more respect. Nobody is forcing you to read my blog. If you don’t like it, don’t read it. I’m glad that you’re skeptical – it’s good to be that way. But calling me “Contreras” and insinuating that I’m making stuff up is just rude – I’ve always been very open and forthcoming.

At any rate, I looked up the data, which is on page 483 of my glute eBook. I was misinformed. Carolyn’s mean glute activity for the deep squat was 17% for upper glute amd 24% for lower glute. During db walking lunges, it was only 7% for upper glute and 13% for lower glute.

And if you read journal articles on glutes, you’d know that these figures aren’t entirely uncommon.

These are mean percentages, the peaks are of course higher. But the squat and lunge involve large periods during the range of motion where the hip isn’t loaded to much degree.

A true scientist reports the data and tries to come up with explanations. I tested her several times because I was surprised myself. So these are the results…what’s your explanation as to why they’re so low?

And shoulders down and back is not a good cue for lifting overhead as the shoulders must upwardly rotate.

Very disrespectful comment, I hope you’ve found my answer satisfactory.

This might be one of the best articles Ive read in 2012. Apart from the great material, it was well written and quite funny. Thanks Derrick and Brett

Thanks Kenny! Glad you liked it. Derrick has a unique style for sure.

Hmmm…”unique”..

Ha ha! You’re being charitable, BC…:)

Kenny, that is a wonderful compliment. Thank you so much!

Hi bret. I like ur The pump Pragram of the newest M&F Mag. but i got a bit confused about the weight using. Should i use max. weights for every single set or gradully increase the weight in a certain set.

And for I don’t have every equpments required. Such as Swiss ball and EZ-BAR,so can i do the simple set up or abs crul up and stright pole cable crul insead of those two workouts.

Lastly and importantly, is this program contain one day for each workout, wihch means five routines per week. And is it a just one month plan or i can use it for couples of months.

Hope my ques. are not a lot.

Thanks Zeg. I need to go buy the magazine…forgot the specifics. Don’t think so much in terms of “maxing out” with pump training, think of squeezing the muscle and trying to get as much blood in the region as possible by keeping constant tension on the muscles. So you’ll go lighter than normal, but not too light. Of course you can substitute movements if you don’t have certain equipment. You can definitely use it for a couple of months. Cheers!

Relly appreciate Bret. Alright last two ques…

each workout takes one single day, so there are totally five strigt in a row and weekends are recreation and rest. Am i correct?

Another thing, before each pump work should i prcribe some warming excrise? For example, workout 1 Quads and Claves, your designed plan contains Squat, Extension and Calf Rise. Can i do a leg press or dumbbel squat with lighter weight as warming-up and accumlate the blood better.

Soryy Bert, i’ve been extremely confused after reading again the article this night.In article, you suggest to start with classic coumpuound excrise which need to perform 3set (10,8,6)Afterwards prescribe five sets of 10 to blow up fast. What’s the actual meaning? is it i need to add 5 sets after each excreise apper on the photo, or i just excatly follow the plan ur designed.

Please answre me, cos i relly interested about the pump. Thanks a lot.

Bret and Derrick,

Interesting work – thank you for including my article in the references and using the “sticky” scapula cue/imagery.

Couple of comments –

Derrick – in the pictures included you seem to be forced to look down (neck and head forward and down) when you actively shrug up – is that intentional and am I seeing that correctly?

In the section about the acromial impingement you don’t mention the SC joint – when the SC joint glides in it’s saddle joint that assists in preventing impingement at the acromion

I have seen fluoroscope images of the “packed” vs. unpacked shoulder and the “packed” shoulder produced more clearance at the AC joint and more correct rhythm during both the Get-up and the Press so I’m not guessing…

For those for whom the cue of pack the shoulder did not feel good:

1) how do we know they have the t-spine mobility and scap control to actually perform the “cue” correctly

2 – Did they actually perform the cue correctly?

I’ve had to teach people how to perform this move correctly enough to know that it can go wrong.

The active shoulder of a gymnastics hand stand results from literally “standing” on your hands – a different situation than pressing while standing on your feet IMO

There are two different “camps” in O-lifting on both the shoulders and the feet:

one camp says to get up on the toes and the other says keep the feet “flat”

one camp says shrug and the other says don’t

Who’s right?

In the end we cannot forget that any “cue” is being applied to an individual.

And that individual may have certain issues we cannot “see” (such as type 2 or 3 acromion) or in my case I have a history of a car accident and a hypo-mobile SC joint on my left so my pressing grooves from Right to Left are different and should be so. (looks interesting too on pics of my 2 KB presses)

Would you agree the Get-up as taught in KBs from the Ground Up is correct for that exercise?

Don’t get so caught in the cues that we forget the individual and what they need based on their individual “make up” so to speak…

Bret,

I very much respect both you and your work and your post makes some great points on cueing. I am particularly interested with regard to your comments re: the packed shoulder position and fluoroscopy. I presently am not aware of any studies that document this information as factual. I have also witnessed fluoroscopy information/images on another internet site and if we’re speaking of the same documented information, it is very interesting and a great starting point. However, the concern is that this information is based on one sole individual i.e. an n=1, thus this may be considered more of an “observation” vs. “fact”.

To make an analogy there is an NFL football who returned to play after high tibial osteotomy. He is the only player in the history of the NFL to accomplish this feat after high tibial osteotomy hence he is also an n of 1.

If there is any additional documented scientific information (actual studies) that you know of in regard to fluoroscopy/imaging and the packing of the shoulder in association with a significant overhead load, I am very interested and would very much appreciate if you could forward that information to me. My e-mail is RPanariello@professionalpt.com.

Keep up the good work.

Rob,

I will see if I can send you the info (I have to check with the individuals involved.).

And I fully appreciate the idea of a sample size of 1 vs. a large sample research study – this is a sample of 1 and might provide a good starting point for further research.

Thanks

Brett

Brett,

I certainly respect your having to “check with individuals”. Any information is certainly appreciated. I also appreciate your efforts.

Rob

Rob,

Those slide and videos are part of a presentation taught by an RKC named Mark Toomey and a Dr. John Damuro (sp?) so I can’t share them but shoot me an email with further questions.

I believe I’ve seen those slides on the internet somewhere. It was several months ago when they surfaced. I tried to find them recently to no avail.

Hi Brett, thank you so much for joining the discussion! I really think that this is how we broaden our understandings of certain training concepts, cues, etc., and this has seemingly gotten harder to achieve in our internet age, when it should have gotten easier. I’m thrilled that we have a real, ongoing and dynamic dialogue going here with some incredibly bright minds participating. To me, this is tremendously exciting, and this is how the internet should work!

In the process of writing this article, I found your post to be as effective a “gap-bridger” between the two ideas as I have found, and maybe if back in the early 2000’s had I access to your expert instruction, I would have been able to perform the cue as properly intended.

Let me try to address your excellent points:

Head position: I do not consciously direct the head in a downwards direction. I am basically looking at the head as part of the spine, and the entire spine as a “global whip”. When working with a straight bar, my intention is to keep the bar as vertically aligned with the spine as possible. Since the head “gets in the way”, there is a slight shift forwards and backwards as the bar clears the head. This is almost analogous to a very slight “kip” as the global whip snaps forwards into place. My head may slightly overcorrect into a slight anterior tilt, this is not by conscious design. I have noticed my head also adopts this position when I am rowing heavy weights, this is the converse of looking slightly upwards when I squat. I try to keep the head roughly in neutral, but I don’t worry too much if it calibrates a bit in either direction, as it causes no pain, and there are bigger fish to fry, so to speak.

T-spine: Concur, concur, concur! I should have renamed my piece: “Strengthen your T-spine!” because I believe it solves so many lifting problems, not just overhead stuff, but squatting and DL’ing, and rowing as well. I wonder sometimes, Brett, if we are focusing on scapular “stickiness” as a workaround for an incorrectly aligned T-spine, in effect asking the lower traps to cover for the weak or inaction of the T-spine extensors. I think the T-spine extensors can never be too strong, and the lower and upper traps can also never be too strong, IF BALANCED with each other.

Cue performance: Obviously if someone (me) is experiencing pain while using a cue, they (me) are by definition, not performing the cue correctly. No cue is designed to provoke pain! I would have never spent so long trying to utilize this idea, if it hadn’t come from one of the most brilliant minds I’ve ever seen, Pavel. Many of Pavel’s ideas are permanently ingrained in my brain: greasing the groove, external torque and spiral shoulder setup, etc. I don’t know if Bruce Lee said it or not, but I do live by: “Adapt what is useful, reject what is useless, and add what is specifically you’re own.”

At some point, much like a brilliant but troubled actor, if a cue is not enhancing the project, then it’s time to recast. (I don’t know why I always think in parables, it’s just the way my mind works, bear with me…)

Closed chain vs. open chain overhead pressing: Great point. As I tangentially alluded to in the piece, I find it an effective tool to try to approximate the stable closed chain “feeling” when performing open chain movements. I have found that the open chain movement’s strength ALWAYS translates to the closed chain strength, while vice versa is not so. For example, when my bench goes up it brings my dip along for the ride, the converse is not true. By the same token, strengthening my free weight version of each lift ALWAYS translates to an increase in the pre-stabilized, machine version.

OLY lifting, and kettlebell get ups: Brett, I personally don’t perform either variant of these strength training styles, save the occasional bout of power, or hang cleans. I really couldn’t say. It’s interesting that there are some differing schools of thought in the OLY world as well, and this reflects what I think we both agree on:

There is no one right or wrong way to cue or process these strength training moves. Individual anatomical differences, relative strength discrepancies, and equally importantly, individual neurological processing differences will dictate how to best get there.

Sometimes, as Rob P. eloquently elaborated above, the body’s form will naturally safely follow the function of the task at hand. Other times, the body is not going to select the ideal form.

Brett, it is an absolute pleasure to discuss these ideas with you. Hopefully I have done a credible job of illuminating my thoughts and experiences. Much respect!

Derrick,

Great to have the chance to have the discussion and learn from each other

” There is no one right or wrong way to cue or process these strength training moves. Individual anatomical differences, relative strength discrepancies, and equally importantly, individual neurological processing differences will dictate how to best get there.”

While I agree with this (and my different pressing grooves right to left are evidence of it) I would say that we have to have a framework to begin from (i.e.. a form we are trying to coach) and we adjust from there.

Good stuff and always great to have discussion on these subjects

Thank you

Thank you for your input Brett…I appreciate you taking the time to comment.

Last sentence should read more like – “we shouldn’t get so caught up…” instead of “don’t”

Thank you, Derrick. However, which one is it then, at lockout, retraction, or protraction? I’m thinking, fairly neutral, and found this bit of advice on gymnasticbodies.com:

http://www.gymnasticbodies.com/forum/viewtopic.php?f=13&t=6718#p60640

“HSPU: You will start in a HS with scaps elevated and upwardly rotated (this happens naturally, just make sure serratus stays active as always so that the scap doesn’t wing out) and straight arms. As you descend, the scaps will rotate downwardly. If you have a good body line there won’t be much retraction or protraction, it will pretty much all be upwards rotation + elevation and downward rotation + depression.”

then

“Handstand: Upwards rotation + elevation(this last part depends on what you want from your HS work, but for our purposes elevation is important).”

Derrick wrote:

“I wonder sometimes, Brett, if we are focusing on scapular “stickiness” as a workaround for an incorrectly aligned T-spine, in effect asking the lower traps to cover for the weak or inaction of the T-spine extensors. I think the T-spine extensors can never be too strong, and the lower and upper traps can also never be too strong, IF BALANCED with each other.”

I am certain this is accurate: the shape (and function) that emerges from the body in response to any demand is *both diagnosis and treatment*, for us, no? This is what the ‘coaching eye’ is all about, for me. Every exercise, every movement, reveals the truth of this, I believe. Great post, Bret, and great follow comments.

Wow! I am amazed by the quaility and magnitude of this discussion!! Thanks Bret and Derrick for stimulating such a magnificient debate. This is the kind of platform we can all learn from and pick up at least one tip/trick we haven’t considered in helping our clients.

Couple of good resources:

1. Study showing increased scapular motion during fatiguing contractions – http://www.jospt.org/issues/articleID.651/article_detail.asp

2. Chapter on shoulder: https://catalog.ama-assn.org/MEDIA/ProductCatalog/m890158/Function%20%20Anatomy%20Ch%204.pdf

So let’s recap based on all the material (article and comments). If I’m in error, feedback is appreciated.