By Eirik Garnas

www.OrganicFitness.com

It’s well established that exercise is important in the prevention of obesity, type-2 diabetes, and other disorders characterized by metabolic disturbances. Also, since people who are overweight on average are less active than lean people, it’s often assumed that the relationship between physical activity levels and body mass index goes in one direction, in the sense that inactivity leads to weight gain. Lack of self-control and “mental weakness” are often considered the primary reasons people have trouble getting off the couch and into the gym, and the general belief is that folks with excess body fat are less active simply because they lack the willpower and discipline to start exercising. But what if it’s not that easy? Correlation doesn’t imply causation, and although a sedentary lifestyle obviously can contribute to metabolic deregulation and weight gain, it’s becoming increasingly clear that it also works the other way around; that weight gain can make you tired and sedentary.

Let’s do a hypothetical example to illustrate the idea behind inactivity and overweight. Patricia, 35 years old, has gained 40 pounds over the last five years and now weighs 180 lbs. While this weight gain is primarily driven by her unhealthy diet, a sedentary lifestyle has also contributed to the poor metabolic health that’s been setting her up for fat accumulation. So, inactivity has been a cause of her weight gain. However, as the pounds have been piling on, Patricia has also noticed that her energy levels have dropped. While she realises that the increased body weight in itself makes it harder to exercise, she’s also starting to believe that other factors might be at play. Is her weight gain making her lazy, fatigued, and less active?

What triggers us to be physically active?

When discussing physical activity it’s helpful to distinguish between obligatory activities (e.g., search for food, avoiding predators), voluntary exercise (e.g., lifting weights, sports), and spontaneous physical activity (e.g., fidgeting, spontaneous muscle contraction). While our ancient ancestors typically had to expend a lot of energy to acquire food, obligatory physical activity is virtually eliminated from the urban, industrialized lifestyle. So, while physical activity was “forced” upon humans for most of our evolutionary history, we have now created an environment where we can choose to be sedentary for most of our lives. Since obligatory activities no longer require a substantial energy cost for most people, I’m primarily referring to voluntary exercise – and sometimes spontaneous physical activity – when discussing the relationship between overweight and inactivity in this article.

But, if obligatory physical activity is rarely required, what drives us to be physically active? There are several factors beside food acquisition and survival that promote activity, such as the feeling, joy, and health benefits you get from exercising. People often complain about the pressure from models and celebrities who display impossible body standards and trainers and nutritionists who urge us to eat well, exercise, and be lean and fit, but the fact is that these pressures also benefit us in the sense that they provide a force that triggers us to exercise. If we only had to expend a miniscule amount of energy to acquire food and survive and there was no pressure to be lean, healthy, and fit, the obesity epidemic would have reached even greater proportions.

Inactivity: A Cause or Consequence of Overweight?

Studies usually show a clear association between activity levels and body weight – with increases in body mass index (BMI) linked with less physical activity (1,2). This basically means that on average, the more fat you carry the more sedentary you are. It’s easy to look at these types of studies and jump to conclusions, but the fact is that they often tell us little about cause and effect. Is inactivity a cause of weight gain? Or are other confounding variables clouding the whole picture? People with a sedentary lifestyle are often less interested in nutrition and health than those who exercise a lot, and other lifestyle characteristics could therefore be responsible for the increased BMI. Or perhaps inactivity is a consequence of overweight? If we take a closer look at some of the studies linking body mass index and activity levels, they actually suggest just this; that overweight is the cause and not the result of inactivity.

In one of these studies, researchers followed 393 men for almost 6 years (2). In line with most other reports, the study found a clear association between body weight and activity levels. However, the study also showed that body weight, body mass index, and waist circumference at the beginning of the study predicted sedentary time at the 5.6 year follow-up, but that sedentary time at the beginning of the study didn’t predict future obesity.

And it also seems to apply in children. When researchers followed 202 children for 4 consecutive years, they found that physical inactivity seemed to be the result of fatness rather than its cause (3). For example, while a high level of physical activity at age 8 didn’t predict fat loss over the next couple of years, a high body fat percentage predicted a decline in physical activity levels.

Animal studies have also shown that activity levels could be a consequence rather than a contributor to weight control (4). In a study published just last month, researchers placed rats on either a standard rat’s diet or a highly fattening junk food diet. During the trial the researchers performed several experiments to test the physical performance of both the rats that developed obesity and those that remained lean, and concluded the following: “We interpret our results as suggesting that the idea commonly portrayed in the media that people become fat because they are lazy is wrong. Our data suggest that diet-induced obesity is a cause, rather than an effect, of laziness. Either the highly processed diet causes fatigue or the diet causes obesity, which causes fatigue” (5).

While it’s important to note that we can’t conclude much from these types of studies, the results question the commonly held belief that inactivity leads to weight gain and instead support the idea that weight gain can be a cause of inactivity.

Your body could be working against you

But how is is that excess body fat can make you tired, lazy, and sedentary? Is it just the additional body weight that’s making it harder to exercise? No. Considerable evidence shows that both voluntary exercise and spontaneous physical activity are under substantial biological control (6,7,8). So, while the factors listed in the beginning of the article, such as discipline, willpower, and the perceived benefits of exercise, certainly play an important role, several hormones, neurotransmitters, genes, inflammatory mediators, and other factors can also impact how physically active we are by influencing our energy-, fitness-, and spontaneous physical activity levels. This explains why overweight and obesity, which are often characterized by hormonal dysregulation and certain genetic predispositions, can cause inactivity. It’s also important to remember that psychological factors play a role, as many people with excess body fat (and many lean people as well) find it uncomfortable to exercise at a commercial fitness center.

When we combine all of these things, it’s no surprise that people who are overweight often find that the perceived cost of exercising outweighs the reward.

Let’s take a look at three of the most important factors linking overweight to a decreased level of voluntary physical activity: Dopamine, leptin, and inflammation.

Abnormalities in brain dopamine activity could decrease your desire to exercise

The modern obesogenic environment, characterized by easy access to highly palatable food, has rapidly decreased our time spent on obligatory physical activity. In essence, we’re no longer forced to move long distances and lift heavy things to acquire food and build shelter. However, as mentioned in the beginning of the article, food acquisition and survival aren’t the only reasons we exercise. Besides the social pressure and personal desire to stay fit and healthy, exercise activities are also sometimes performed because they are rewarding and pleasurable (e.g., the runner’s high).

Just like obesity is often characterized by a degree of food “addiction”, the neurobiological rewards associated with physical activity – such as euphoria and reduced anxiety – can help explain why some people essentially become addicted to exercise. These effects seem to be partially mediated by neurotransmitters, such as dopamine, which impact the reward value and perceived cost/benefit of a certain activity and thereby help determine how likely we are to seek out a specific behaviour again and again.

Individual differences impact our response to exercise, and while people who love running or lifting weights find these types of activities highly rewarding, obese people often have abnormalities in brain dopamine activity that could help explain why they are less likely to engage in voluntary physical activity and/or need a greater stimulus to get the same feeling as someone with normal dopamine functioning (6,9).

High leptin levels and/or leptin resistance can decrease physical activity levels

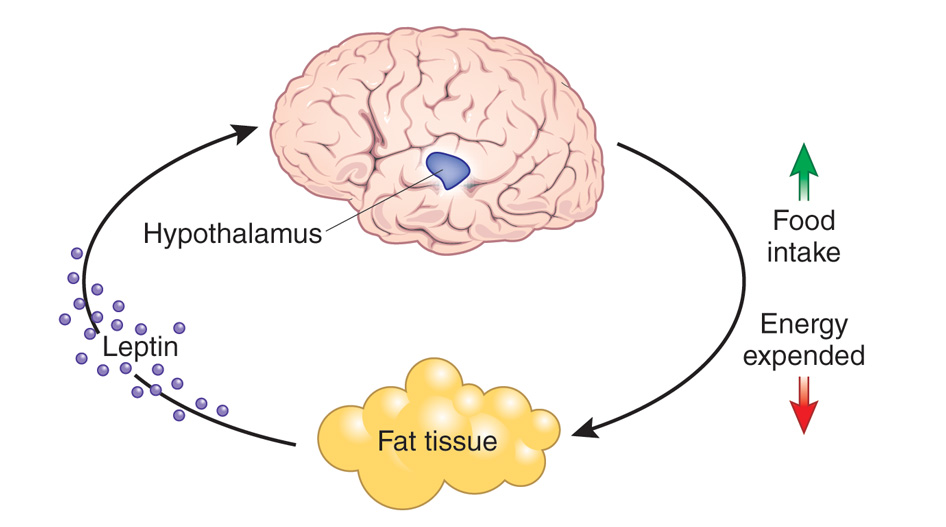

One of the hormones that’s tightly linked to both weight regulation and activity levels is leptin. Leptin is secreted by fat cells and is responsible for regulating long-term fat storage by triggering a response in the hypothalamus. When body fat stores go down, leptin production also decreases, and the brain responds to the lowered leptin signaling by increasing our interest in food and decreasing energy expenditure (e.g., muscle contractions, body heat production) in an attempt to restore body fat levels. Since leptin production correlates with the size of our fat stores, people who are overweight have elevated levels of systemic circulating leptin.

It’s well established that leptin can impact locomotor activity, heat production, and other factors that determine our energy expenditure by triggering a response in the central nervous system. Some evidence also suggest that leptin impacts voluntary physical activity levels, as high leptin levels have been shown to predict a decline in moderate to vigorous physical activity (10,11,12), while very low levels of circulating leptin could be a primary cause of the hyperactivity often seen in patients with anorexia nervosa (very low levels of body fat) (13).

So, low leptin levels, as seen in anorexia nervosa and other conditions characterized by depleted body fat stores, seems to promote hyperactivity, while high levels of circulating leptin, as seen in overweight subjects, has been associated with hypoactivity. One theory is that this feedback system between fat cells and the brain benefitted us in an ancestral natural environment since it helped us maintain body fat levels within a certain range; increased fat storage and leptin production would have discouraged us from engaging in physical activity (e.g., foraging), while low levels of circulating leptin would have encouraged us to actively seek out food. This system would have worked perfectly in a hunter-gatherer environment, but has backfired completely in the modern obesogenic environment characterized by food abundance and very low levels of obligatory physical activity.

However, while it’s very clear that leptin impacts activity levels, there are some loopholes to this theory. First of all, low leptin production doesn’t always lead to hyperactivity as seen in anorexia nervosa. Also, although obese people have higher levels of circulating leptin, obesity is characterized by leptin resistance, a condition where leptin produces a smaller response at the receptors in the brain – essentially tricking the hypothalamus into believing that the body carries a lot less body fat than it actually does. Mice who lack a functioning leptin receptor in the brain become obese, diabetic, and abnormally inactive, but activity levels rapidly increase after restoration of leptin receptors (14).

Low-grade chronic inflammation associated with overweight and obesity can lead to tiredness and fatigue

In my mind, low-grade chronic inflammation is the most important factor linking overweight to lower levels of physical activity. Contrary to the acute inflammation that occurs when you sprain your ankle or get a wound, low-grade inflammation is often a fairly silent condition. Chronic low-grade inflammation can be a consequence of chronic health problems, such as in obesity where fat tissue releases many inflammatory mediators, but itís also clear that inflammation can be a cause of disease. Altered gut microbiota and increased production of inflammatory mediators in fat tissue are two of the primary reasons why people people with excess body fat usually have higher levels of pro-inflammatory compounds in the blood. This state of low-grade chronic inflammation can decrease physical performance and make you tired and fatigued (15,16,17,18,19).

What does all of this mean?

Weight gain and inactivity are linked through a vicious cycle, where a sedentary lifestyle contributes to poor metabolic health, low-grade inflammation, and excess fat storage, and weight gain further contributes to inactivity. The fact that inactivity isn’t just a cause of weight gain, but also a consequence, is important to have in the back of the mind when dealing with weight regulation and obesity.

While it’s often believed that exercise is just a matter of willpower and discipline, science clearly shows that other factors also play a significant role. While some people have no problem exercising every day and find physical activity to be highly rewarding; genetic predispositions, poor metabolic heath, mental barriers, and low-grade chronic inflammation can make exercise seem like hell to others. This doesn’t mean that we don’t have control over our own actions and that people who carry excess fat don’t have a choice except to stay sedentary – it just means that individual differences play an important role.

The expanding view of the relationship between activity levels and body composition have implications not only for people who lack the desire to exercise, but also for trainers, health practitioners, and other personnel that work with health and fitness. For people who feel fatigue and tiredness have been keeping them back from having an active lifestyle, it might come as a relief that it’s not just a lack of discipline that makes the trip to the gym seem like a nightmare.

I’ve coached many overweight and obese clients over the years and spent a fair amount of time observing what goes on in the gym. One of the things I’ve noticed is that people with a high body fat percentage sometimes seem like they are in hell during a hard workout. This is far from a universal observation, but in general it seems that obese trainees find exercise to be extremely strenuous and hard – it’s just no fun at all. This observation that fatness can lead to inactivity, laziness, and inferior efforts in the gym is something most trainers and coaches have probably witnessed. While the general belief is that this hardship results from the excess body weight they have to carry around, a lack of desire, poor conditioning and/or some type of mental “weakness”, it’s becoming increasingly clear that abnormalities in brain dopamine activities, leptin resistance, low-grade chronic inflammation, and other conditions that often go hand in hand with obesity also play a significant role. Also, it’s important to note that these mechanisms aren’t just relevant to those that carry too much fat.

All of these things are something trainers should have in the back of their mind when coaching clients.

In the end I think it’s important to say that you are still in control of your own health. Voluntary exercise is ultimately about making a choice and setting up a plan. Also, if you’re overweight and feel that the information in this article applies to you, weight loss is the best way to regain control of your body and become more active.

Let’s go back to the question in the beginning of the article: Is inactivity a cause or consequence of overweight? In the end, I think it’s safe to say that it works both ways: Inactivity can be both a cause and consequence of weight gain. My bet on what is most important: Overweight–>Inactivity

About the author

Name: Eirik Garnas

Name: Eirik Garnas

Website: www.OrganicFitness.com

![]() Besides studying for a degree in Public Nutrition, Iíve spent the last couple of years coaching people on their way to a healthier body and better physique. I’m educated as a personal trainer from the Norwegian School of Sport Sciences and also have additional courses in sales/coaching, kettlebells, body analysis, and functional rehabilitation. Subscribe to my website and follow my facebook page if you want to read more of my articles on fitness, nutrition, and health.

Besides studying for a degree in Public Nutrition, Iíve spent the last couple of years coaching people on their way to a healthier body and better physique. I’m educated as a personal trainer from the Norwegian School of Sport Sciences and also have additional courses in sales/coaching, kettlebells, body analysis, and functional rehabilitation. Subscribe to my website and follow my facebook page if you want to read more of my articles on fitness, nutrition, and health.

This is an interesting concept – I’ve also noticed that when the severely overweight also start eating “cleanly” as well as exercising, it seems to help with the listlessness, which makes a lot of sense after reading your article.

Covered some old ground with some fresh ideas. Good work Eric.

In my personal experience getting the overweight to believe in the health benefits of exercise, starting slowly and that high intensity program advertised on TV and such is not the only way to go. Low intensity can be just fine, for fat loss at the start of their journey.

Great points! Being overweight is definitely a precursor to inactivity. The freedom (mentally and physically) experienced when weight loss/better eating habits/training patterns occur is life changing to watch. We all have the power to achieve great things

Interesting. So, as you gain weight, you exercise less and gain more weight. But does it follow that as you exercise and lose weight, it becomes even easier to continue to exercise and to lose even more weight? The hardest step is the beginning?

Can’t be quite that simple, because there are many examples of people who lose substantial amounts of weight, and then regain it all. Still, once you reverse a vicious cycle, you hopefully enter a virtuous cycle.

Exercise usually isn’t very effective for weight loss.

If you lose weight in a healthy way (diet and lifestyle changes, not starvation/strict calorie restriction) that lowers the inflammatory tone and reduces the range of defended body fat, then you should also experience increased energy levels.

However, there are many terrible approaches to weight loss, where you’re literally fighting against your body and therefore quickly regain most of the lost weight after you’re no longer on a calorie restricted diet. Check out this link if you want a summary of what works: http://organicfitness.com/evidence-based-guide-to-weight-loss/

Here is a great article about leptin resistance and how to fix it. Really good evidence based information that I found very helpful. I think leptin rsistance is my problem that I have to deal with. http://www.leanhealthyandwise.com/how-diet-and-exercise-reverse-leptin-resistance/

great, great, great! these kinds of articles, that challenge “intuitive” concepts like “inactivity –> obesity”, are a) the reason we dont think any more that the sun goes round the earth and b) admit it: are far more exciting. 🙂

reminds me of a very similar paradigm shift: your attitude towards something determines how u behave, right? nope. the attitude towards a specific topic (and the attempt to change it “for the better”) has shown to be a remarkably bad predictor on what you actually do. dozens of practical examples come to mind. just think of your new year´s resolutions. convinced? 😉

instead, doing something, the behavior, is a surprisingly good predictor of attitude change. a huge body of evidence has explored finer minutiae, restrictions, extensions and implications of that general principle.

this finding is today regarded as one of the milestones of modern social psychology.

Great article, as usual. Keep up the good work!

I am going to read your reviews of good methods to loose weight. I feel great since I started paleo eating and weight lifting, and have more energy than ever, but there are many people I love that hesitate to embark in the same boat… Maybe because they are too overweight?

“We must learn time & again, that our food must be our medicine & our medicine should be contained in our food.”

-JXXD-.

Eirik, Initially, your making a grave mistake putting overweight and obese people through gym sessions immediately, especially when you consider there internal health is suffering (the organs, brain, blood, tissues, ligaments, joints & so on). You even have the word ‘fatigued’ in the title. What sort of a state is that to be in when exercising?. How can the body ever function correctly?.

Obviously feeling fatigued/lacking energy is a key reason why many overweight people give up too early.

So the initial emphasis has to be on (detoxing/cleansing/strengthening/regenerating) internally & resting. You have to place considerable importance on the internal health & get that in full working order first & foremost, then ease them slowly back into exercising with just taking gentle strolls/walks. I have always believed the best form of exercise is walking (preferably in a green environment).

You have to remember that for many people who are overweight/obese, it’s taken them many, many years to progress to such a stage & as such, it’s not going to be a quick fix (obviously), but the planning needs to be more subtle IMO & longer term. Believing extreme circumstances require extreme measures is wrong. They have to keep in mind how long it took them to put the weight on when trying to take the weight off.

Many of them are not being guided properly.

Hi Eirik,

I really like the depth of your article. Before I started training an using elliptical I used to be fat to and I recognise my behaviour in your description. Keep it up.

Very interesting; great article. Thank you!

This is what I am experiencing now entering middle age! I hope you don’t mind but I am going to link to this on my blog. Thank you.