Individual Differences: The Most Important Consideration for Your Fitness Results that Science Doesn’t Tell You

By James Krieger and Bret Contreras

Preface: The idea for this article was sparked last year when James and I presented together in the UK at the Personal Trainer Collective Conference along with Brad Schoenfeld and Alan Aragon. At that time, I had done a ton of research on the genetic differences pertaining to fitness outcomes, but I hadn’t yet seen a lot of data reporting individual differences. James’ presentation was filled with graphs depicting the stark differences in individual results, and it dawned on me that this is probably the most important aspect of science that fails to be reported. We hope that in time it becomes standard practice to report individual data, but in the meantime, we wish to impress upon you that research typically only reports means, which may or may not apply to you.

Consider the following scenarios:

· Your friend swears by high intensity interval training (HIIT) for losing body fat. In addition to increased caloric expenditure from the session, she notices a boost in overall energy throughout the day, which she claims helps her burn even more calories. Yet every time you employ HIIT, you notice that the scale doesn’t move. Moreover, it seems to just make you tired and exhausted, which prevents you from achieving stellar strength training workouts in the gym, thereby sabotaging your efforts to build strength and muscle.

· You read an article saying that deep squats are the absolute best thing you can do to build your legs and hips. But every time you perform them, your hips and low back are beat to smithereens and you can’t train legs again for another 10 days. The persistent pain you experience prevents you from using your muscles to their fullest potential.

· Your training partner says steady-state cardio makes her hungry. She notes that she has a harder time adhering to her diet when she does cardio compared to when she omits it altogether. You, on the other hand, consistently lose your appetite after a cardio bout. Cardio therefore seems to help you create an even greater energy deficit.

· At the gym, you overhear a bro bragging that all he has to do to build his pecs is a few sets of push-ups close to failure each week and he grows like crazy. You can’t seem to get anywhere unless you’re doing 15-20 sets of various pec exercises per week, though. He claims that your workout is overkill and creates too much damage and soreness, but you recover just fine from your routine.

How can we know who is right? Maybe everyone is.

Often we like to turn to research to tell us how to structure our diet and training programs, and studies certainly can act as guidelines or starting points. We must remember, however, that in general, research reports averages. Individual responses to exercise and diet can vary dramatically from one person to the next; averages don’t provide us with this information.

In this article, we’re going to delve into some critically important yet seldom discussed considerations in evidence-based fitness programming.

To Cardio or Not to Cardio for Body Composition Improvements?

Although there are numerous “non-responders” to aerobics training, meaning that they cannot improve their aerobic capacity, insulin sensitivity, or blood pressure through cardio (see HERE), this section deals more specifically with those who train primarily for aesthetics. Let’s say you are considering adding cardio to your fat loss program. You’d ideally want to consider a number of factors, including but not limited to the effect of cardio on your:

· Appetite and food intake

· Daily energy levels and non-exercise activity

· Sleep quantity and quality

· Resistance training focus (i.e., Does it interfere with your ability to train progressively and set personal records?)

· Willpower throughout the rest of your day (i.e., Do you lose discipline in other components of your training and diet?)

Let’s take a closer look at some of these elements.

Cardio and Appetite

At first glance, cardio does not appear to have much of an impact on appetite or calorie intake (see HERE for a recent meta-analysis). However, this doesn’t tell us the whole story. Take a look at THIS study where researchers looked at people’s calorie intake responses to a 50-min low-intensity cardio session at 50% of max heart rate. The researchers looked at the compensatory response to the exercise session. In other words, if you burned 100 calories in a workout, would you then make up for it by consuming 100 calories later?

The following graph shows the variation in compensatory eating from one subject to the next. The solid line indicates where calorie intake was equal for the exercise and no-exercise conditions, meaning there was no compensation at all (i.e., the subjects did not eat food to make up for the calories burned in the exercise session). The dashed line indicates where the subjects perfectly compensated for the calories burned during exercise (e.g., if they burned 100 calories, they ate 100 calories). Thus, subjects between the solid and dashed line showed only some compensation (e.g., burning 100 calories but eating 50), while subjects at or above the dashed line showed perfect or overcompensation (meaning they ate more than they burned in the exercise session).

Look at the wide variation in responses.

Look at the wide variation in responses.

A couple of people ended up with 300-600 calorie deficits after the exercise session, yet several people ended up with 300-600 calorie surpluses! The former group saw amplified results on account of their decreased caloric intake following the cardio session, whereas the latter group sabotaged their fat loss efforts by consuming more calories than they burned during the cardio session.

How does this apply to you? Are you a person who feels extremely hungry after low-intensity cardio? Then perhaps it’s not for you. Or maybe you’re a person who doesn’t get hungry, or even loses appetite, in response to low-intensity cardio. If that’s the case, low-intensity cardio might be a good way to help you establish an energy deficit to lose fat.

It’s been shown HERE that people who tend to compensate for exercise by eating more are people who have a preference for high-fat, sweet foods; these individuals have a very high hedonic, or pleasure, response to these foods. So, if you’re a person who really loves cake, ice cream, and so on, and tend to have a weakness for these foods, then low-intensity cardio might stimulate your appetite. In your case, then, you can try things like interval training (some research suggests it may suppress appetite, although the data is not consistent), or skip cardio altogether.

Cardio and NEAT

Let’s take a look at the impact of structured exercise on Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT). NEAT refers to all of your physical activity throughout the day that does not include formal planned exercise – everything from fidgeting to walking to your car to maintenance of posture to moving your mouth. NEAT plays a powerful role in weight regulation and is just as important as exercise when it comes to energy expenditure. Now, what happens to NEAT when you embark on a structured exercise program? Well, according to THIS study, the answer is, “it depends”.

The researchers had 34 women engage in a 13-week brisk walking program. Some women experienced an increase in physical activity energy expenditure, yet others experienced a decrease! How could this be? It’s because some of the women compensated for the exercise by decreasing their NEAT levels. Perhaps the exercise made them tired, or maybe they thought that, since they exercised that day, they were free to sit around the rest of the day. Whatever the reason, each subject responded differently to the exercise program in terms of NEAT levels.

Below is a chart showing the differences in physical activity energy expenditure between the women who didn’t reduce NEAT and the women who did.

You can see how low the physical activity energy expenditure was for the women that reduced NEAT compared to the women that didn’t, especially on the non-exercise days. These women became so sedentary the rest of the day that their inactivity more than negated the benefits of the exercise. Other women responded positively to the exercise and experienced an increase in energy expenditure. Again, we have dramatic differences in how individuals respond.

You can see how low the physical activity energy expenditure was for the women that reduced NEAT compared to the women that didn’t, especially on the non-exercise days. These women became so sedentary the rest of the day that their inactivity more than negated the benefits of the exercise. Other women responded positively to the exercise and experienced an increase in energy expenditure. Again, we have dramatic differences in how individuals respond.

How does this apply to you? Do you feel so exhausted after a cardio session that you sit around the rest of the day? If that’s the case, the cardio may be doing you more harm than good because it’s reducing your NEAT. But if you feel energized and active, then the cardio is likely an effective fat loss tool for you. Again, it’s how you respond individually, something the research can’t always tell you.

Cardio and Sleep

Exercise tends to be good for sleep. See HERE for a recent meta-analysis. It can even help insomniacs (see HERE). However, some individuals experience exercise-induced sleep problems. In fact, according to THIS study, 53.9% of 256 college students felt that strenuous physical activity extremely negatively impacted their sleep. There’s a large genetic component to the sleep-wake cycle and its disorders (see HERE), indicating that some individuals are more predisposed to exercise-related sleep issues than others. A recent meta-analysis (see HERE) found that elite athletes experience a high overall prevalence of insomnia symptoms including longer sleep latencies, greater sleep fragmentation, non-restorative sleep, and excessive daytime fatigue, and these patterns are worse on training days compared to non-training days. Many find that sleep disturbances tend to be worse with physical activity performed with greater intensity and in closer proximity to bedtime.

How does this apply to you? If you find that cardio seems to improve your sleep, then you should indeed consider regularly performing cardio, especially considering that sleep and muscle mass are positively related according to THIS study. However, if you instead find that cardio interferes with your sleep, then you should consider omitting it altogether, especially given that diminished sleep duration and quality are linked to obesity, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, and mortality (see HERE).

Cardio and Progressive Resistance Training

The interference effect associated with cardio and strength training was first established in 1980 in THIS study. Since that time, we’ve learned a great deal about the molecular mechanisms and training variables responsible for the interference. A little cardio isn’t going to kill your gains. Up to a point, strength and endurance increase concomitantly. However, when endurance training is carried out frequently enough, with sufficient intensity, for a prolonged enough duration, it will indeed interfere with strength, hypertrophy, and power adaptations.

But this subsection isn’t about the interference effect per se. What we want you to consider is whether or not you tend to give your resistance training your all if you did cardio that morning or if you know you have to do cardio later in the evening. Consistently gaining strength and setting PRs is very challenging. It requires tremendous focus, grit, and determination. One study showed that challenging cognitive tasks impaired subsequent push-up and sit-up performance (see HERE). Sure, cardio isn’t a mental task, but THIS paper suggests that anything and everything can impact physical performance. Sometimes cardio can distract you from making meaningful strength gains in the gym, and the weight room is better suited than cardio at helping you transform your physique.

How does this apply to you? If you’ve noticed that cardio negatively affects your strength training performance, you could try lower intensity cardio such as brisk walking, making sure to spread the sessions out as much as possible during the day. You could alternatively omit cardio altogether and save your physical and mental energy for the gym. But if you find that cardio doesn’t impact your ability to focus on your strength training sessions, then by all means, feel free to employ some cardio. After all, most pro bodybuilders do cardio and it’s obviously not hampering their gains.

Cardio and Ego Depletion

According to some research, willpower is a finite resource that gradually drains and replenishes itself throughout the day and night. When faced with stressful tasks, people use up their willpower and tend to exhibit less self-control later in the day. This is known as “ego depletion,” and it’s the subject of a good number of experiments in the literature.

For example, exerting self-control causes people to consume more food, but there are many factors that appear to influence the relationship between ego depletion and food intake, including BMI (see HERE), confidence surrounding one’s ability to regulate weight (see HERE), and impulsivity (see HERE). Furthermore, some individuals are much more sensitive to the effects of ego depletion than others, according to THIS study.

How does this apply to you? Let’s say that you’re a morning person, you enjoy running in general, you love being outside, you have a nice running trail that starts a block away from your house, and working up a nice sweat before your work day starts makes you feel confident and productive. In this case, you seem like a good candidate for cardio. On the other hand, let’s say you cringe every single morning at the thought of performing your cardio (there’s a strong genetic component to enjoying exercise according to THIS, THIS, and THIS paper), you have to drive 40 minutes to get to your gym where you do your cardio, and you loathe driving in rush hour traffic. In this case, it is very likely that stubbornly sticking to your morning cardio regimen would deplete your self-control and cause you to exert less willpower later in the day. This could result in greater caloric consumption and possibly greater indulgence of junk foods, which would sabotage your attempts to become leaner and healthier. If the latter scenario describes you, it is likely that you’ll see better results by omitting cardio altogether. Sometimes simpler is better.

Resistance Training and Strength & Hypertrophy

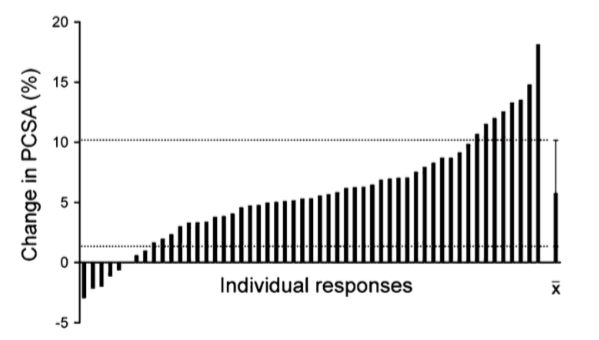

There’s a lot of variability in how much muscle you gain in response to a particular training program. Check out a chart from THIS study. It shows the percent change in muscle physiological cross sectional area of the quadriceps. Fifty-three previously untrained subjects performed 4 sets of 10 rep leg extensions with 80% of 1RM and 2-minute rest periods between sets 3 times per week for 9 straight weeks. We would assume that each subject would gain substantial levels of strength and muscle during this time period, right?

The bar on the far right shows the average increase in muscle, which is around 5%. But look at the tremendous variation between individuals. The changes ranged from a -2.5% to a nearly 20% change in muscle size. While most people experienced an increase, five of the subjects actually lost muscle. Interestingly, genetic predispositions to hypertrophy are muscle-specific, meaning that you can likely grow certain muscles quite easily while others seemingly refuse to grow (see HERE). This is evident when you consider THIS study which examined 45 men and found that one man had 484% (almost 5X) more glute volume than another man.

The bar on the far right shows the average increase in muscle, which is around 5%. But look at the tremendous variation between individuals. The changes ranged from a -2.5% to a nearly 20% change in muscle size. While most people experienced an increase, five of the subjects actually lost muscle. Interestingly, genetic predispositions to hypertrophy are muscle-specific, meaning that you can likely grow certain muscles quite easily while others seemingly refuse to grow (see HERE). This is evident when you consider THIS study which examined 45 men and found that one man had 484% (almost 5X) more glute volume than another man.

Changes in strength also show marked variation from one person to the next. Check out the individual results of THIS study which examined concurrent training, that is, training strength and endurance at the same time.

This graph represents the isometric leg press force gained over a 21-week period of training. One subject got 12% weaker, while another subject got 87% stronger! How in the world does an untrained individual get weaker after strength training twice per week for roughly 4 months? Nevertheless, this study also showed that the high responders in terms of aerobic capacity were not high responders in maximal strength. Another study showed that high responders to strength training can gain markedly more strength performing 2 weekly sets of squats per week than medium and lower responders can from performing 8-16 sets of squats per week (see HERE).

This graph represents the isometric leg press force gained over a 21-week period of training. One subject got 12% weaker, while another subject got 87% stronger! How in the world does an untrained individual get weaker after strength training twice per week for roughly 4 months? Nevertheless, this study also showed that the high responders in terms of aerobic capacity were not high responders in maximal strength. Another study showed that high responders to strength training can gain markedly more strength performing 2 weekly sets of squats per week than medium and lower responders can from performing 8-16 sets of squats per week (see HERE).

These dramatic patterns of strength and hypertrophy responses are very predictable in the literature as they have been replicated in numerous studies. Some folks can gain strength or muscle quite easily while others cannot (see HERE). Interestingly, however, those who gain the most strength aren’t always the same individuals who gain the most muscle and vice versa. There’s a large genetic component to this phenomenon, and we know that muscle growth has much to do with how your satellite cell system functions and how much growth factors you produce (see HERE). Hell, according to THIS study, testosterone levels of male Olympic athletes range from 58 ng/dL to 1154 ng/dL (average is 420 ng/dL), and in females the range is from 0 ng/dL to 923 ng/dL (average is 78 ng/dL).

Individualization of Program Design

All of this information indicates that you need to consider how you respond individually to changes in training and diet in order to determine your optimal program design. You can use science to give you an idea of where to start, but ultimately it takes individual experimentation to learn what is going to work for you.

For example, let’s say you are designing your resistance training program. You need to think about how you respond as an individual to factors such as:

· Volume

· Frequency

· Load

· Effort

· Exercise selection

Consider volume, for example. THIS very recent meta-analysis on volume and hypertrophy indicated that, for optimal hypertrophy, you should do 10 or more sets per muscle group per week. However, once again, this is based on averages. For example, 15 weekly sets might work great for your training partner, but you find that anything more than 8 and you get nothing but sore joints. The type of exercise also matters; 10 weekly sets of leg extensions is not the same as 10 weekly sets of squats. Moreover, due to genetic variation, some individuals gain more lower body strength with a single set compared to multiple sets (see HERE).

Anatomical Joint Range of Motion

Your anatomy can impact exercise selection. Many exercises require a good deal of joint range of motion in order to be executed properly. If your skeletal structure does not allow your joints to move through the range of motion that a particular exercise requires, then you will not be able to properly perform that exercise.

Think of the hip joint. Many popular knee dominant exercises necessitate sound levels of hip flexion mobility in order to carry out properly. For example, the deep squat, leg press, high step up, and pistol squat each appear to involve at least 120 degrees of hip flexion at the bottom of the movement. Once your hips run out of range of motion, if you continue going deeper, you can only do so by posteriorly tilting your pelvis and flexing your lumbar spine (this is commonly known as “butt wink”). While some butt wink is acceptable, too much is dangerous and likely to lead to hip and low back issues.

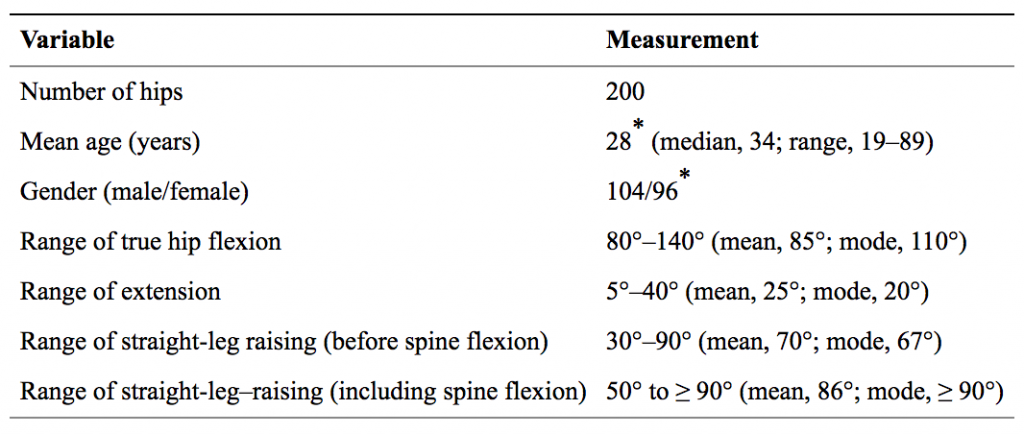

Take a look at the table below from THIS study.

The researchers examined the hip flexion mobility of 200 subjects. There was a 60 degree difference in mobility between the least and most flexible individuals. The least flexible person could only attain 80 degrees of hip flexion, whereas the most flexible person could reach 140 degrees. The former person couldn’t even squat to parallel without butt winking, whereas the latter individual could squat rock bottom with no problems.

The researchers examined the hip flexion mobility of 200 subjects. There was a 60 degree difference in mobility between the least and most flexible individuals. The least flexible person could only attain 80 degrees of hip flexion, whereas the most flexible person could reach 140 degrees. The former person couldn’t even squat to parallel without butt winking, whereas the latter individual could squat rock bottom with no problems.

How does this apply to you? If you have good mobility, then you can likely perform most exercises with textbook mechanics, which is excellent because greater range of motion is typically shown in the research to lead to superior hypertrophic outcomes. However, if you possess grossly inferior mobility, then you will likely get beat up from exercises that take those joints into a deep stretch. In addition to the aforementioned exercises, this could apply to dips, dumbbell bench press, push ups off of handles, flies, stiff leg deadlifts, good mornings, and more.

While it is obvious that these exercises can easily be modified in order to suit an individual’s anatomy (just go as deep as your body comfortably allows), most people who are lacking in mobility tend to go deeper than they should in an attempt to make their range of motion appear more normal, and this leads to problems at the shoulders, hips, and low back. If this accumulates and leads to nagging pain, it will prevent you from achieving optimal hypertrophy since pain inhibits muscle activation.

Genetic Propensity to Muscle Damage

Your physiology can also influence exercise selection, in addition to volume and frequency. Some individuals experience greater muscle damage than others due to genetics and therefore require more recovery time in order to repair the damage (see HERE). Moreover, some individuals are much more susceptible to experiencing tendon and ligament injuries (see HERE, HERE, and HERE).

How does this apply to you? Some people can bust out 5 sets of squats, deadlifts, and lunges and feel fine the following day, while others are crippled for several days following the same workout. If you’re the type that doesn’t get overly sore and recovers quickly, then you can train with more volume and frequency than others and you don’t have to give much thought to exercise selection. However, if you experience tremendous soreness from common workouts and seem to take forever to recover, then you can either 1) train less frequently (not ideal in our opinion), 2) train with less volume, 3) train with less effort, and/or 4) select exercises that don’t create as much soreness (exercises that stress the stretch position such as stiff-legged deadlifts and lunges create more damage than exercises that stress the contracted position such as back extensions and hip thrusts).

Conclusion

Determining how you respond individually to alterations in training and diet are extremely important in establishing the right pathway to achieving your goals. Just because the research suggests that X is beneficial, doesn’t mean that it is beneficial for YOU. Or, just because another person swears by Y, doesn’t mean Y is beneficial for YOU.

The best fat loss program for you may involve cardio – or it may not. The best strength training program for you may involve deadlifts – or it may not. The best hypertrophy program for you may involve training each muscle group 3 days per week – or it may not. Moreover, what is best for you now may not be best for you next month, or next year, or in the next decade.

There are so many variables to consider, and science is only just beginning to examine how individuals respond to these variables. There are strong genetic components to practically every single variable that impacts your ability to gain muscle, lose fat, increase strength, and improve athleticism. You must therefore utilize the scientific method and experiment in order to figure out what works best for you.

The research can guide you on where to start, but only you can determine where you finish.

About James

James Krieger is the founder of Weightology. He has a Master’s degree in Nutrition from the University of Florida and a second Master’s degree in Exercise Science from Washington State University. He is the former research director for a corporate weight management program that treated over 400 people per year, with an average weight loss of 40 pounds in 3 months. His former clients include the founder of Sylvan Learning Centers and The Little Gym, the vice president of Costco, and a former vice president of MSN.

James Krieger is the founder of Weightology. He has a Master’s degree in Nutrition from the University of Florida and a second Master’s degree in Exercise Science from Washington State University. He is the former research director for a corporate weight management program that treated over 400 people per year, with an average weight loss of 40 pounds in 3 months. His former clients include the founder of Sylvan Learning Centers and The Little Gym, the vice president of Costco, and a former vice president of MSN.

James is a published scientist, author, and speaker in the field of exercise and nutrition. He has published research in prestigious scientific journals, including the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition and the Journal of Applied Physiology. In his previous lay publication, Weightology Weekly, he wrote over 70 articles per year covering the latest science in a manner that was friendly and easy to understand. James is also the former science editor for Pure Power Magazine, and the former editor for Journal of Pure Power, both publications that delivered scientific, but lay-friendly, information on training and nutrition to athletes and coaches. In addition, James has given over 75 lectures on fitness-related topics to physicians, dietitians, and other professionals, and has been a speaker at major events such as the AFPT Conference and NSCA Personal Training Conference. In fact, James has been involved in the health, nutrition, and fitness field for over 20 years, and has written over 500 articles. He is a strong believer in an evidence-based, scientific approach to body transformation and health.

Great article. I can hip thrust 205 lbs and have a tiny butt. Go figure.

I am curious about the individual variability in responses to the different mechanisms of hypertrophy. Are there any studies that show various individual adaptations to muscle damage versus metabolic damage? How about rep ranges?

Anecdotally, heavy hip thrusts get an excellent pump going and are my favorite exercise but if I am looking to really make some serious glute gains I need to incorporate split squats and lunges for muscle damaging effect.

Awesome, love it and hate it. I feel like I’ll be trying programs throughout my whole life before I find what works best for me (and my booty) ):

Terrific article, Bret and James. Definitely shows how important it is to self-experiment and track your individual response to training, nutrition, etc.

I’m 72, 147lbs with to much body fat, 5’7″ height, exercise 5 X per week for around 90 minutes, MW upper body, T TH lower body, Fri is a general body day with the focus on cables & machine work rather than DB or BB. Some days are circuit training days when I’m bored with my usual routine. Cardio using HIIT is daily with either treadmill, elliptical or stair master for no more than 20 minutes. I do yoga postures for balance. I lack flexibility. Thus my squats & deadlifts aren’t perfect and I use a light weight to compensate for this. I’ve been using weights since I was 14. I like fencing. I’m not good at it. Can you suggest exercise for fencing? I’ve never been good at any sport activity, e.g., football, baseball, soccer, etc. That’s one of the reasons I started lifting when I was 14. Fencing is fun

I liked your article above. I’ve believed your info for many years.

Thanks

Amazing article!

Going out in our weekly science review Saturday. Well done guys. Great review.

Great article. Congratulations from your brazilian fan!

This is precisely why articles promoting the actual training programs of superstars are bad advice: They are, by definition, genetic outliers, so what works for them won’t work optimally for the “middle of the bell curve” people. Ronnie Coleman’s mass building program, Usian Bolt’s speed work, and 85-year old marathon star Ed Whitlock’s “training secrets” probably work well for people with their very unique genetics. The optimal programs for the rest of us are something else.

Fantastic article!

This article really hits the nail on the head by explaining the variability that needs to be addressed in everyone’s training programs. No two people are alike and research has shown this. Thanks for a great post and ill be sure to share it!

Thanks for this article. It’s amazing how many variable are at play. I’m in the midst of off season training for road cycling and it’s a challenge to figure out how best to opimize my training. This helped!

Great article and you guys are amazing for bringing all that information. My personal experience – Haven been heavy load hip-thrusting and bridging till I am blue in the face and only quads are burning,. But take 30 pound barbell and squat and lunge – and cant sit on my butt for 3 days, lol. Guess my body responds to those better. Everyone is gifferent and unique and I always felt I need to listen to what my body tells me.

This topic is fascinating. I had this exact conversation with a personal training client last week who was comparing her body comp results to family members. “They try less but look better”. Can be quite frustrating but we all need to find the approach that suits our bodies, our preferences, our own goals, our schedules, etc. Otherwise we are destined to fail and end up on the merry go round of fads. Thanks for sharing guys.

“Take a look at THIS study where researchers looked at people’s calorie intake responses to a 50-min low-intensity cardio session at 50% of max heart rate.”

The link on “THIS” is not right

After 16 months of Orange-theory fitness I look the same as when I started. I have dieted for periods at different calorie levels and I have also eaten-regularly (and I really like food). Either way, I look the same. I think I am one of the people who flat-lines in the graphs above. I wonder if there is a resource for people like me that tells us what method of exercise is best? If I give up on aesthetics as my goal–is it necessary to be going twice a week to Orange-theory for health benefits? Or should I just take walks from time to time or do the 1 minute HIIT exercise each day… Can you suggest an article or a direction? Thanks!

Thanks for putting this together :))

Some researchers have not been able to replicate the ego-depletion effect suggesting there’s more to it, and further research is needed.

“Multiple laboratories (k = 23, total N = 2,141) conducted replications of a standardized ego-depletion protocol based on a sequential-task paradigm by Sripada et al. Meta-analysis of the studies revealed that the size of the ego-depletion effect was small with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) that encompassed zero (d = 0.04, 95% CI [−0.07, 0.15].”

Hagger, M. S., & Chatzisarantis, N. L. (2016). A multilab preregistered replication of the ego-depletion effect. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(4), 546-573.

Fantastic article! Butt winking and associated back pain is a common problem that I see in a lot of the powerlifters in my community. Those who can’t get deep enough on squats without experiencing spinal flexion are often tasked with the challenge of deciding between their long-term back health and the ability to compete in the sport they love.