Today’s article is a guest-blog from my colleague Chris Beardsley. This was intended for the blog on the research review site, but I convinced Chris to let me post it here. There isn’t a single study in the literature examining the effects of squat depth with relative loading (same percentages of 1RM) on gluteus maximus activity! In the meantime, all we can do is speculate based on existing studies and scientific rationale.

About the author

Chris Beardsley is a co-founder of Strength and Conditioning Research, a monthly publication that summarizes the latest fitness research for strength and sports coaches, personal trainers, and physical therapists. Chris also writes a regular blog in which he reviews some of the latest developments in Biomechanics.

If you spend any time talking with Bret, you’ll quickly find that one of the fastest ways to get him going is to say something like “research shows that the activation of the glutes increases with increasing squat depth.” Quite seriously, it’s the most fun you can have without an entertainment license.

And while it is technically correct that a study was performed that showed increasing gluteal activation (relative to the other leg muscles) with increasing squat depth, this study had some rather peculiarities in its data set and a pretty large limitation.

In fact, what we’ll see is that research doesn’t really have an opinion about what happens to gluteal activation with increasing squat depth right now. It’s something we need to find out.

The study: The Effect of Back Squat Depth on the EMG Activity of 4 Superficial Hip and Thigh Muscles, by Caterisano, Moss, Pellinger, Woodruff, Lewis, Booth and Khadra, in Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2002

***

Background

There are not actually that many studies that have investigated the EMG activity of squats during different conditions, and with appreciable weight. However, we should note the following:

- Wretenberg (1996) investigated the differences between both parallel and full, high- and low-bar squats using weightlifters and powerlifters. They reported that the powerlifters, who used the low-bar squat, displayed higher levels of EMG activity in all muscles at both depths. They also found that the low-bar squat tended to produce higher hip moments than knee moments, while the high-bar squat tended to have more equal hip and knee moments.

- McCaw (1999) compared various different stance widths and found that stance width did not appear to affect the EMG activity of the key hip extensors and knee extensors. They also showed that quadriceps activity in general was much higher than the activity of the hamstrings and gluteals.

- Escamilla (2001) similarly found no differences in the muscle activity of a number of muscles during different squat stance widths but for some reason omitted to investigate the gluteals.

- However, since then, Paoli (2009) have found that the gluteus maximus is more activated during wider stance squats than during narrower stance squats. Like McCaw, they also showed that quadriceps activity in general was much higher than the activity of the hamstrings and gluteals.

Moving away from squats for a moment, let’s consider the EMG activities and behavior of muscles at various joint angles, because joint angle dictates muscle length, which affects EMG activity.

- Signorile (1995) explored how the muscle activity of the vastus medialis, vastus lateralis and rectus femoris during isometric contractions at 90 degrees, 150 degrees, and 175 degrees knee angles. These researchers found that the 90 degree knee angle (i.e. 90 degrees flexion) produced greater activity than the 175 degree knee angle (i.e. 5 degrees of flexion) for these quadriceps muscles. So this would suggest that the quadriceps would be more active during deeper squats.

So, in summary, based on our (very brief!) literature review, we are expecting to see the EMG activity of the quadriceps increase significantly with increasing squat depth, especially in comparison with the other leg muscles. However, we don’t really know what is going to happen to the other muscles.

***

What did the researchers do?

Basic study set-up

The researchers wanted to investigate the EMG of four leg muscles (the biceps femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus medialis and gluteus maximus) during squats of different depths (partial, parallel and full).

So they recruited 10 young males who had more than 5 years of experience in resistance training and monitored the EMG activity of these muscles while the subjects performed squats to the various depths with a weight of c. 100 – 125% of bodyweight. This weight was kept the same for all squat depths, which is an important point to which we will return later.

***

An unusual EMG normalization approach

EMG activity levels are typically normalized to a reference value, most commonly a maximum voluntary isometric contraction. For some reason, at the outset of this study, the researchers wanted to normalize their EMG data using a 1RM squat. However, they didn’t use this method, as it was found to be unsuccessful because the subjects kept leaning forwards excessively during their 1RM attempts and turning them into good mornings.

Therefore, the researchers decided to use a completely relative measure instead, in which they simply compared the EMG activities of the muscles to one another at various points. So when they report percentages for the EMG of each muscle, they are reporting it as a fraction of the total EMG measured and not to a maximum voluntary isometric contraction (MVIC).

Again, this has very important ramifications for when the researchers report their results, because it means that if one set of muscles decreases in activity, the others all go up.

***

Usual EMG normalization for the gluteus maximus

Normally, when performing EMG activity analysis, researchers normalize their data to a MVIC using a dynamometer in a position that is known to elicit a very high level of muscle activation. These positions are generally used with reference to previous studies and while they may not necessarily be perfect, they do allow for a degree of standardization.

For the gluteus maximus, it is important to recall that Worrell (2001) showed using a dynamometer that the gluteus maximus is most active in 0 degrees of hip extension compared to 30, 60 or 90 degrees of hip flexion. This is quite crucial, because if researchers use 90 degrees of hip flexion when they are testing MVIC, then according to Worrell, they are testing to 64% of MVIC and not 100% of MVIC.

Additionally, Fischer and Houtz (1968) showed that the gluteus maximus is most active when the knee is flexed. So we need 0 degrees of hip flexion and 90 degrees of knee flexion for maximal gluteus maximus activation for our MVICs. To show you that I am not making this up, you can see that these two key points are (mainly) adhered to by researchers in three large, recent reviews.

- Ekstrom (2007) – the MVIC was performed prone, with the knee flexed to 90 degrees and the hip extended with resistance applied just above the knee.

- Ayotte (2007) – the MVIC was performed supine and the hip was placed in 30 degrees of flexion while the knee was in 90 degrees of flexion. So we don’t quite get full hip extension for our MVIC but it’s a lot better than 90 degrees of flexion.

- Distefano (2009) – The MVIC for the gluteus maximus muscle was tested by resisting maximum-effort hip extension, performed with the subject lying prone on a treatment table, with the knee flexed 90 degrees.

And what is the point of telling you all of this? The point is that when researchers want to contract the gluteus maximus in an MVIC, they use 0 degrees of hip flexion and 90 degrees of knee flexion. But squats involve either 0 degrees of hip and knee flexion together or 90 degrees of hip and knee flexion together. At no point do we get 0 degrees of hip flexion with 90 degrees of knee flexion in a squat.

So is increasing squat depth likely to lead to increased gluteal activity? Well, the answer to that question is going to depend on which factor (hip angle or knee angle) is relatively more important in influencing activity, along with the external joint torques associated with those ranges of motion. But the answer certainly isn’t obvious.

***

What happened?

Concentric phase

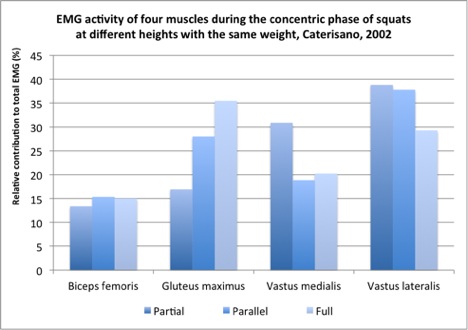

Here’s what the researchers recorded for the concentric phase. They noted that the only significant trend was for increasing gluteal activity with increasing depth. However, in addition to this, you’ll note that there are some odd trends within the quadriceps.

We noted in the background that Signorile (1995) found that increasing knee flexion led to increased quadriceps activity. So these results seem very strange indeed, even though the researchers are keen to point out that the changes in vastus medialis activity were not statistically significant.

Eccentric phase

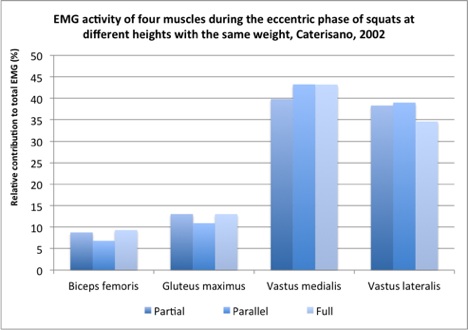

However, the researchers did not obtain quite such odd results with their data that they recorded of the eccentric phase. Here’s the chart:

Here, while we don’t see a steadily increasing trend, as we would expect based our previous knowledge, at least the levels of activity in the quadriceps aren’t reducing with increasing depth. However, it does imply that the concentric and eccentric phases are very different from each other.

Comparing the concentric and eccentric phases

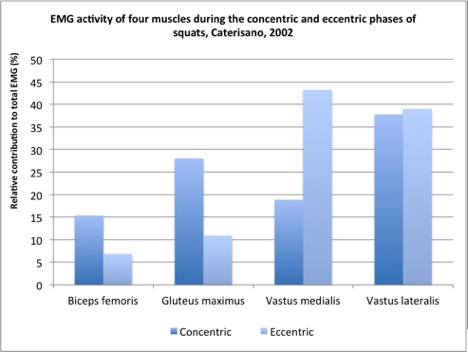

The following chart shows both concentric and eccentric phases together for the parallel position. You can see that the hip extensors are both much higher in the concentric phase compared to the eccentric phase, while the vastus medialis is hugely decreased in the concentric phase, as if it is almost not needed.

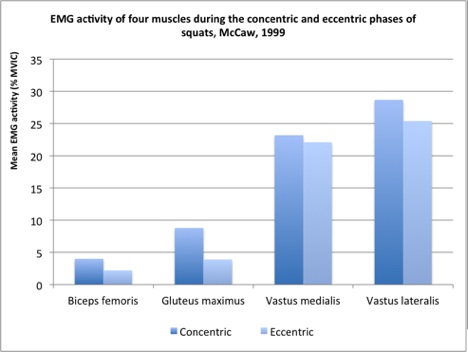

For reference, the relative activity level is 19 ± 9% in the concentric position and 43 ± 11% in the eccentric position. When I saw that difference, the first thing I wondered was whether this large discrepancy between eccentric and concentric activity was normal for squat EMG. So I dug out the McCaw (1999) and graphed it. This is what I found.

So here, we can see that while there does appear to be a trend for greater hip extensor activation during the concentric phase, the differential isn’t as great as it appears in Caterisano. On the other hand, the vastus medialis data just looks really odd because the eccentric phase is very much higher than the concentric phase in Caterisano but slightly lower than the concentric phase in McCaw.

At this point, I wondered whether the small sample size (10 subjects), or an equipment malfunction or odd placing of the electrodes in one of the trials with one of the subjects might have led to an odd result being produced. Obviously, I can only speculate.

I would note, however, that Paoli (2009) shows a similar trend to McCaw, in that the vastus medialis is of a similar level of activity to the vastus lateralis, although it doesn’t provide a split between concentric and eccentric. Also, when Shaub (1995) investigated the ratio of the vastus lateralis and the vastus medialis in the squat, they concluded they had broadly equal contributions. So this odd behavior of the vastus medialis in this study would appear to be the exception rather than the rule.

Now, bear in mind that in most EMG studies this would only affect the results for the muscle concerned. And this is the reason that I am belaboring the point. In this study, this is really important because of the unusual way in which the normalization was performed. Since the EMG activity of each muscle is normalized relative to the other muscles, if there was an error in measuring the activity of one of the quadriceps, then this could overestimate the activity of the other muscles.

Interestingly, we do observe a higher-than-expected level of activity in the hip extensors. And, also very interesting is that we only observe the big increase in gluteal activity with depth in the concentric phase (where the error in the vastus medialis might be) and not in the eccentric phase (where the vastus medialis looks relatively as expected).

***

Limitations

So, while you were reading about the peculiarities of the data set, I bet you forgot about the big limitation I mentioned at the beginning, didn’t you? Well, the major problem with measuring EMG activity of various muscles at different squat depths and comparing the results of different depths to each other is that… it’s a lot harder to squat deep.

So when you use 1-times bodyweight to squat deep, it might be 50% of your maximum squat. However, if you squatted that same weight to a partial depth, it would probably only be 25% of your maximum partial squat. So the EMG activity at partial squat depth is ALWAYS going to be less than the EMG activity during full squats, unless you use a percentage of 1RM for each depth.

***

What did the researchers conclude?

The researchers concluded that the gluteus maximus changes most in its activity levels according to depth. They also concluded that the activity of the vastus medialis and vastus lateralis was not affected by squat depth.

Noting that they only used sub-maximal weights and that their results may not therefore be applicable to heavy resistance training, they therefore suggest that the gluteus maximus is more active during deeper squats and that deeper squats could therefore be used for rehabilitative exercises requiring gluteal activation.

I don’t agree with either of those conclusions, because:

- In this study, only the concentric phase shows a change in gluteus maximus activity with depth. If you look at the eccentric phase, the EMG activity of the gluteus maximus doesn’t change with depth.

- This study shows a big difference in the EMG activity of the muscles between concentric and eccentric phases.

- Other squat studies don’t show big differences in EMG activity between the eccentric and concentric phases.

- This study shows a big decrease in vastus medialis activity with increasing depth in the concentric phase. This is counter to what other studies have shown: Signorile (1995) showed that quadriceps activity was much higher at 90 degrees of knee angle (90 degrees flexion) compared to 175 degrees of knee angle (5 degrees flexion). Moreover, Bryanton (2012) and Lorenzetti (2012) both showed that increased squat depth requires greater knee extension (quadriceps) moments, which would imply that greater activation would also be expected.

- This study used relative measures of EMG activity between muscles. So the big decrease in the vastus medialis activity in the concentric phase, which runs counter to expectations, could have made the observed increase in the gluteus maximus significant when in reality it was not.

- This study used the same weight for partial, parallel and full squats with an (estimated) 50% 1RM load at the full squat level. This is equivalent to using 50% of 1RM at the full squat level, 40% at the parallel level and 25% at the partial level. Completely different results might be expected if 50% of 1RM were used at each depth.

***

So what can we conclude?

I don’t think we can conclude anything this study because of (a) the strange results that appear to disagree with the results of many other studies, and (b) the fact that they used the same weight at each depth, making comparisons between depths difficult.

***

What do I predict actually happens?

I would guess that if the researchers have used a bigger sample and had used the correct 1RM at each depth, then this study would likely have shown relatively decreasing hamstring and gluteal activity with increasing squat depth but relatively increasing quadriceps activity. I say this because I think that quadriceps activity most likely increases with increasing squat depth. However, I don’t really have a strong view on whether the absolute levels of gluteal activity would increase with increasing squat depth.

When I asked Bret about this, he said that his guess was that you might get a slightly greater gluteus maximus activation associated with the stretch-reflex as a result of squat depth (but then he asks do the glutes really ever get stretched much?). However, on the other hand, he noted that the external moment decreases slightly once the lifter descends past parallel, so parallel might well provide the greatest gluteal EMG. He also noted that gluteal EMG during partial squats would be strongly affected by whether the lifter “sits back” into the squat and absorbs the load with the hips. In this case, the gluteal EMG during heavy partials might be similar to those in deeper (but necessarily lighter) squats. He noted that when body parts come into contact with each other at the bottom of a squat (back of thigh with calf, belly with upper thighs), there is some elastic recoil that takes some load off the hips. Finally, he suggested that since the knees are fully flexed at the bottom of a squat, this would force more contribution onto the glutes and away from the hamstrings due to active insufficiency. Then he finished by saying that he doesn’t know the answer, but he guesses that the differences wouldn’t be remarkable.

Ultimately, whether gluteus maximus activity increases with increasing squat depth will only be resolved once someone goes and does a study to find out what happens. It will likely depend on whether hip or knee angle and the associated external joint moments at the particular ranges of motion using the same relative loading is more important in determining gluteal activity. If this sort of thing is right down your alley, then you would likely love our new product Hip Extension Torque: The Scientific Guide to the Posterior Chain.

Really interesting work Chris, if a little frustrating!

It made me wonder if there’d be any merit in using something like a Lever Squat machine that’s Isokinetic and calling for maximum exertion from the subject at different depths. I know this would eliminate the eccentric part of the movement, but at least you’d have a true 1rm to measure at each height.

Hi Trevor, long time no chat!

It is frustrating but it’s even more frustrating that many people have been citing this study’s conclusions without actually taking the time to see the problems with it. That has led to some very misleading assumptions about both squats and glute training becoming very common.

I am actually currently talking to a group of researchers at the moment about the possibility of doing the study again. I like your suggestion but I do think it can be done with normal barbell squats, it just needs a lot more work to get 1RMs at several heights and perform submaximal efforts at those same heights.

Hope all is well,

Chris.

Exactly! Maybe 85% of 1RM for deep, parallel, and partial squats. 3 reps. Look at mean and peak. Make sure the lifters sit back a bit with the partials and don’t just bend the knees.

Also do isometric pauses (3 seconds) at the bottom of the rep with the various loads at the various depths.

Would make an amazing study.

I think it would be good to look at EMG data for isometric squats at different heights.

Yep! Agree my friend!

Great review and critique guys, I actually only read this study for the first time a few weeks ago, your awesome work here has made it clear not to take its claims too seriously. thanks

I was hoping for an interesting answer in this post – it was a great read, but no great answer, I guess.

Had my hip replaced a year ago, and have a sad, sad squat at the moment. Feels that I need to mobilize my mid-back in order to get more depth from my squat..

Maybe because you reach the end of your range of hip flexion and then the pelvis wants to pull your spine into posterior pelvic tilt (making you feel it in your mid-back)? If this is true, then you should NOT aim for more depth in the squat and should just be complacent with going as deep as you can while keeping great form and feeling it in the right places. Do you have good levels of hip flexion ROM?

A huge limitation to this type of study would be the depth the participant can squat to without losing a neutral spine. Wouldn’t that make a massive difference? Subject A had a certain amount of glute activation below parallel but lost their neutral spine at the quarter squat position. Not sure how valuable anything like this is unless all of that stuff is completely accounted for. Calling a squat a squat is not accurate if you are dealing with completely different biomechanics from one person to the next. Moreover, almost all that research done at different joint angles and whatnot seems a little… I don’t know… worthless, again, not knowing how well the body you are testing works. You really aren’t coming up with any accurate conclusions unless you account for the function of the individuals or do it on a large enough scale where that is not an issue anymore.

I see your point, but another study we’ve looked at (which was surprising) showed that glute activation didn’t change in APT or PPT. So if they lose neutral spine, the glute may be able to still fire well. You see this in certain Oly lifters…I remember watching Pat Mendes do this on every rep, are you gonna tell him his glutes aren’t working right? 😉

So the degree of posterior tilt and lumbar flexion would be of most importance, and some may be acceptable at the bottom of the squat, but too much would definitely throw things off.

In the case of this study, all subjects had over 5 years of weight training experience and could reach full squat depth just fine, according to the authors. So this is not a limitation in this particular study.

So Brett in order to get maximum glute hit in order to gain size and shape and overall firmness for men what would you ultimately suggest ? What do you suggest to your male clients and not your female ones ?

Same for males and females…hip thrusts, squats, deadlifts, lunges, back extensions, swings, etc., along with various accessories such as plank, posterior tilt, abduction, and external rotation movements. I lay it all out in my book Strong Curves.

Great work yet again Bret and Chris. I will be purchasing your new e-book very soon.

Just one quick question Bret, i mentioned in a previous post that the gluteus maximus is predominantly slow twitch. I read a while back (not sure where) that the glutes along with the hamstrings and gastrocnemius are the most powerful muscles in the body. I would have expected the glutes to be more fast twitch dominant. But i guess fiber composition is only one factor in how powerful a muscle is.

btw, i meant to say “you mentioned”

This age old debate! What form of squat is the best for knee health? I have had clients over the years say parallel is most comfortable, then other have complained their knees hurt going ATG. Most of them, myself included have crepitus in the knee – which is painless – just sounds nasty!

For maximum quad/glute et. al. development is ATG the best way to go? Our biomechanics lecturer many a year ago suggested training in the ROM that was required for your particular sport – ie; mixed martial artist very rarely goes ATG, so they should squat for explosive power only in the ROM that they’re using. I was a little confused by all this!

Keep up the good work guys.

To follow up Sam’s point, I’d like to hear thoughts on the periodization of ROM as it relates to attempting to make things more specific by going short to long on the ROM. Plenty of track coaches think this is the way to go.

Chris and Bret, you state the major limitation of this study as follows:

“So the EMG activity at partial squat depth is ALWAYS going to be less than the EMG activity during full squats, unless you use a percentage of 1RM for each depth.”

However, as you noted in this more recent post: http://www.strengthandconditioningresearch.com/2013/01/30/practical-training-tips/

“The researchers observed that activity of the rectus femoris and erector spinae were both higher during the 90-degree squat than during the 45-degree squat despite the heavier weight being used in the 45-degree squat.” (yes, too bad they didn’t measure gluteal activity!)

Does that possibly (even partially) overcome the limitation of Caterisano? Any further insights you can offer? Thanks for the thought-provoking posts…

Hi Ben! What an excellent question my friend (love that you’re a fellow biomechanics afficionado).

I thought about this same thing when I went through the more recent study and here are my thoughts.

The erectors and rectus are indeed going to be more active in the deeper squat as they’ll need to fire harder to create an anterior pelvic tilt torque to counteract the posterior pelvic tilt torque induced by going into deeper hip flexion (in other words, to stabilize the pelvis).

However, the glute max won’t have to stabilize the pelvis in this case (posterior pelvic tilt isn’t necessary) so it just functions as a hip extensor (and a bit of external rotation torque too). Therefore, glute activity probably won’t change that dramatically as you’ll get similar hip extension torques through the different depths. Since torque has a load and a distance component, you get greater loads and smaller perpendicular distance with partials, but smaller loads and greater perpendicular distance with the parallel squat. Of course, this is making assumptions with form though.

Just my two cents – looking forward to more research emerging in this area. Again, great question Ben!

Hey Bret, thanks for your response! That gives me even more to think about…

I’ve previously referred to Caterisano as providing one piece of supporting evidence for deep squats, so I appreciate the fresh perspective. I’m admittedly biased toward squatting deep (while acknowledging the potential utility in doing partials) and this post definitely poked a little hole in my argument.

I am too (I feel the stretch in the glutes more when I go deep, and it just seems like common sense) – so I always assumed this would be the case (greater glute EMG at greater squat depths). However, when I did some EMG experiments on myself, I saw that this was not necessarily the case. I realized that a new stud would need to be conducted using the same %’s of 1RM with the different depths. Until then, we can still quote Caterisano with some caveats. Cheers Ben!

Great article and collection of studies, thanks very much.

I had always big butt… but after few months of Reg Park routine which involved full squat and front squat my butt went even bigger… jenifer lopez is flat arse comparing to me….

Not that I wanted it… becauce I didn’t… Now I am trying to do parallel squats but my lower back got tired really quick and it aches even with only 50kg!!!! (I do 12 reps slowly)

I alost think that Weighted Hyperextension works glutes too…

Check my old training log

http://www.fitocracy.com/profile/tgchan

Weighted Hyperextension

19.5 kg x 10 reps 52

22 kg x 10 reps 54

24.5 kg x 10 reps 56

27 kg x 10 reps 58

Front Barbell Squat

80 kg x 5 reps 91

90 kg x 5 reps 106

100 kg x 5 reps 123

100 kg x 5 reps 123

100 kg x 5 reps (PR) 123

Barbell Squat

80 kg x 5 reps 87

90 kg x 5 reps 101

100 kg x 5 reps 117

100 kg x 5 reps 117

100 kg x 5 reps (PR) 117

Standing Barbell Shoulder Press (OHP)

45 kg x 5 reps 71

50 kg x 5 reps 76

55 kg x 5 reps 82

55 kg x 5 reps 82

55 kg x 5 reps (PR) 82

Barbell Bench Press

70 kg x 5 reps 77

77.5 kg x 5 reps 86

87.5 kg x 5 reps 100

87.5 kg x 5 reps 100

87.5 kg x 5 reps (PR) 100

Bent Over Barbell Row

47.5 kg x 5 reps 30

55 kg x 5 reps 33

60 kg x 5 reps 36

60 kg x 5 reps 36

60 kg x 5 reps 36

Barbell Deadlift

82.5 kg x 3 reps 72

92.5 kg x 3 reps 84

102.5 kg x 3 reps 97

102.5 kg x 3 reps 97

102.5 kg x 3 reps (PR) 97

Standing Barbell Press Behind Neck

35 kg x 5 reps 39

40 kg x 5 reps 42

42.5 kg x 5 reps 43

42.5 kg x 5 reps 43

42.5 kg x 5 reps (PR) 43

Barbell Curl

25 kg x 5 reps 14

27.5 kg x 5 reps 15

30 kg x 5 reps 15

30 kg x 5 reps 15

30 kg x 5 reps 15

Lying Barbell Triceps Extension (“Skullcrusher”)

25 kg x 8 reps 16

27.5 kg x 8 reps 17

30 kg x 8 reps 17

30 kg x 8 reps 17

30 kg x 8 reps 17

Standing Barbell Calf Raise

40 kg x 25 reps 16

50 kg x 25 reps 19

60 kg x 25 reps 22

60 kg x 25 reps 22

60 kg x 25 reps 22

total workout time: 2h 30min

In my opinion best things for your glutes are:

1. Weighted Hyperextension

2. Front Barbell Squat

3. Full Barbell Squat

4. Barbell Deadlift

I have been training for 7/8 months on this routine and my ass grew like a pumpkin.

Now I want to avoid and seperate my glutes from training but it is hard… parallel squat feels awkward now and it bothers my lower back even with 50kg… and I have never felt a thing during full squat… + I don’t know if front squats activate glutes same way as back squat and if should I keep doing the full ass to grass front squats or also parallel one…

Prior this routine I was doing 120kg x 5 but parallel squats and I have not noticed any big difference in my butt.

Hey Brett,

Just wondering, what are your thoughts on squatting on a plank or two 2.5kg plates?

Not sure if its good for my knees or not. I’ll get shoes eventually.

Thanks,

Anthony

Hi Chris and Bret,

Really enjoy reading your articles gentlemen.

Could the explanation of greater vastus medialis activity in the partial squat of the Caterisano 2002 study be the down to the fact the in the last 15 – 20 degrees of knee extension there is more activity in vastus medialis, hence why physiotherapists doing rehab exercises aimed to target the VMO do variations of step-ups (such as the Peterson step-up) and look at exercises that involve the latter part of knee extension?

Could Bret take the most popular VMO exercises and do a study to see which elicits the most EMG activity? On “youtube” Charles Poliquin shows a “quad squat” and a “Peterson Step-up” to bring up the strength on VMO, would you gentlemen have a similar opinion on VMO?

Interested to hear your opinion on VMO isolation exercises?

All the best guys

James

Question, please email me so I can hear your thoughts, when you go atg your feet must be at a wider stance, does that maybe result in more glute activation rather than just atg? I ask because I just did some front squats atg paused and my glutes have never felt fuller.