Many strength coaches are big on rotary strength and stability. While we love our Pallof press movements, which fall under the “core stability” umbrella since the core remains stable, we also love our cable chop and lift movements and our landmine movements, which may or may not fall under the “core movement” umbrella depending on how the movements are performed (with or without spinal rotation), in addition to med ball rotational movements.

Some coaches feel that spinal rotation strengthening should be avoided completely, some coaches believe that spinal rotation strengthening should be performed but the movement should occur at the thoracic spine and the hips while the lumbar spine is locked down, and some coaches think that spinal rotation strengthening is great and you don’t need to cue anything because the body is smart and knows how, where, and when to rotate.

In Mike Boyle’s article entitled, Is ‘Rotation Training’ Hurting Your Performance?, he quotes Shirley Sahrmann, who states the following:

The thoracic spine, not the lumbar spine should be the site of greatest amount of rotation of the trunk… when an individual practices rotational exercises, he or she should be instructed to “think about the motion occurring in the area of the chest.”

Mark Buckley does an excellent job of discussing the biomechanics of spinal rotation exercises in this free PDF. He states that:

Rotation is not the concern – where the rotation takes place is the concern

Mark goes on to state that thoracic rotation accounts for 60-70° (Segmental contribution as high as 7-10° in the mid thoracic area at T3-T9) of rotary movement in the spine, while lumbar rotation only accounts for 10-15° (Segmental contribution as small as 0-2° at L1-L5 and 0-5° at L5-S1) of rotatry movement in the spine.

Our Lumbar Spines are Jacked

In this article, Eric Cressey pointed out that in this study, it was shown that in the lumbar spine:

52 percent of the subjects had a bulge at at least one level, 27 percent had a protrusion, and 1 percent had an extrusion [82% of subjects]. Thirty-eight percent had an abnormality of more than one intervertebral disk

Our Thoracic Spines are Also Jacked

Last year I was pulling up research pertaining to the thoracic discs, and I stumbled upon some interesting and perplexing information. This study states that thoracic hernations occur with much less frequency than lumbar or cervical hernations. This study reports that thoracic hernations are responsible for only .15-1.8% of all spinal herniations.

However more recent research paints a different picture. In this study involving 90 individuals, 37% of asymptomatic individuals had at least one thoracic disc herniation, 54% had a disc bulge, 58% had an annular tear, 29% had deformation in the spinal cord, and 28% had Scheurmann end-plate irregularities or kyphosis. And this study, conducted in 2007, which claims to be the largest study in the world’s literature on the topic of thoracic disc herniation, states that thoracic disc hernations occur in 50% of patients and that 26% of patients had multiple herniations. This study states that degenerative disc disease and disc herniations are the most prevelent thoracic spine abnormalites and that disc herniations predominate in the lower thoracic segments and are a dynamic phenomenon.

Disc Herniations are in Flux

Interestingly, while disc degeneration does not improve, thoracic herniations are in a state of constant flux. This study shows that 27% of disc herniations improved over a 4-149 week range of follow-up. After a mean follow up period of 26 months, 48 previously looked at discs in this study were examined, and they found that 3 of 21 small disc herniations increased in size, one of twenty and three of twenty medium discs increased and decreased in size respectively, and four of seven large disc herniations decreased in size.

Method of Imaging Matters

It appears that the method of imaging matters, as this study showed that 21 of 48 thoracic discs appeared healthy when using MRI, but when using discography only 10 of 48 appeared normal. Studies involving discography likely underestimate spinal abnormalities.

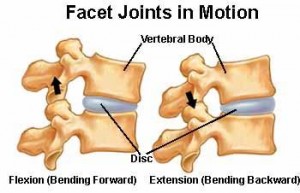

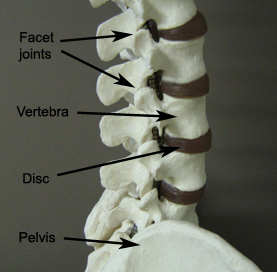

Torsion Hammers the Lumbar Facets (But Extension and Lateral Bending are Worse)

This study shows that lumbar facet joints carry no load in flexion, and large loads during extension (205 N at a 10 Nm moment and a 190 N axial load), torsion (65 N at a 10 Nm moment and a 150 N axial load), and lateral bending (78 N at a 3 Nm moment and a 160 N axial load).

Thoracic Facet Joint Pain vs. Lumbar Facet Joint Pain

This study showed that the prevalence of facet joint pain was 39% in the cervical spine, 34% in the thoracic spine; and 27% in the lumbar spine.

This study showed that painful thoracic facets occurred in 42% of individuals with thoracic pain, while only 31% of individuals with low back pain suffer from painful lumbar facets, however of the 500 people with chronic spinal pain involved in the study, only 6% had painful thoracic facets and 25% had painful lumbar facets. During the background portion of the article, the authors stated that, “facet joints have been implicated as a cause of chronic spinal pain in 15% to 45% of patients with chronic low back pain, 48% of patients with thoracic pain, and 54% to 67% of patients with chronic neck pain.”

Poor Hip Mobility Most Likely Increases the Risk of Low Back Pain in Rotary Sport Athletes

This study stated that “Among people who participate in rotation-related sports, those with LBP had less overall passive hip rotation motion and more asymmetry of rotation between sides than people without LBP.”

This makes perfect sense, as individuals possessing insufficient hip internal and external rotation mobility will be forced to compensate and rotate more at the lumbar spine. Over time this will usually result in injury and/or pain if left unchecked.

Rotational Exercises are Safer With Some Axial Pre-Loading

In this article, Nick Tumminello quotes the late, great Mel Siff:

A certain degree of compressive preloading locks the facet assembly of the spine and makes it more resistant to torsion. This is the reason why trunk rotation without vertical compression may cause disc injury, whereas the same movement performed with compression is significantly safer.

Some Things You Need to Think About

Let’s say that a certain movement requires 60 degrees of spinal rotation. Do you want all 60 degrees of rotation occuring in the 12 thoracic motion segments with absolutely zero motion occuring in the five lumbar motion segments?

Would this be the safest method of execution, and is this a natural movement pattern?

Or, would it be safer if the individual rotated (for example) 55 total degrees in the twelve thoracic motion segments and 5 total degrees in the five lumbar segments? Is some lumbar rotation natural and beneficial, or do you want to completely “lock it up” by cueing all motion in the chest/t-spine area?

Aren’t end ranges of spinal motion the most dangerous for the discs? Wouldn’t we want to distribute load evenly rather than concentrate it in one region?

Does architecture (ie: what the lumbar spine and thoracic spine were built for) matter when thoracic discs and facets get beat up just like the lumbar discs and facets?

Are spinal rotation exercises even worthwhile considering they are high risk? Should we ever do any spinal rotation under load, or is it wiser to stick to just rotary stability exercises for the spine where the spine stays motionless while rotary forces are resisted/prevented?

Segmental vs. Fluid Rotation

Nick Tumminello talks about segmental rotation in this video:

My Take

It is very important to first qualify individuals for proper hip and thoracic spine rotational mobility. If they don’t have it, you need to prescribe mobility drills until they get it. Here are a bunch of different t-spine rotational mobility drills:

Here are some hip mobility drills:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XEwfxa_9_y8

While you are developing hip and spine mobility, you can simultaneously work on preventing torsion by prescribing rotary core stability exercises such as band or cable rotary holds or foam roller prone and supine rotary holds.

Next, you can introduce a dynamic component and have individuals prevent spinal rotation while the limbs are moving dynamically. These include cable chops, cable lifts, landmines, and tornado ball slams. Finally, you can incorporate some slight motion in the spine via various types of chops, lifts, landmines, and medball throws, but you want to make sure that individuals are moving at the proper segments. If you followed the correct steps, then individuals should be able to distribute loading efficiently and rotate with a combination of hip and t-spine rotation with slight motion at the lumbar spine.

To reiterate, there’s a 2-step process:

1. Increase hip and t-spine mobility and work on static rotational core stability

2. Move to dynamic rotational core stability and eventually rotational strength with some spinal movement involved

As far as cueing to “move at the chest,” I believe that it’s best to err on the side of caution and try to get most of the mobility in the t-spine rather than involving the lumbar spine. Even though discs at all spinal regions appear to take a serious beating and develop herniations, and even though facet joint pain seems to occur at all spinal regions as well, it makes sense to look at the architecture of the spine and try to determine its optimal function.

Furthermore, many novices erroneously believe that spinal rotation should occur mostly in the lumbar spine and they therefore actively attempt to twist to end-range lumbar rotation. This is highly dangerous. If individuals think of movement occuring in the chest, they’ll stay tall and properly distribute stress over a broad range of joint structures which will minimize tissue damage and the likelihood of injury. I’m sure that even when individuals attempt to lock down the lumbar spine there is still some slight (but not dangerous) motion involved.

Evidence shows that there is a huge genetic component to disc degeneration and herniations. While trainers and coaches like to believe that we can prevent the onset of spinal degradation by teaching the body to move properly via mobility, stability/activation drills, and proper cueing for motor control feedback, it appears that there is only so much we can do.

I only perform (myself) and prescribe (to clients) spinal rotation work twice per week and stay away from end ranges. Two sets of 6-10 reps is the typical volume. One day per week usually involves anti-rotation (the spine stays neutral and resists rotation), while the other day involves actual rotation (the spine twists a bit).

What’s your take? Are spinal rotation movements worth the risk? If so, where should the rotation occur, how should the exercises be cued, and how frequent should they be prescribed?

As usual Bret a great article full of insight and excellent source material, keep up the great work it’s inspiring.

Thank you Peter! I appreciate the compliment.

Bret,

Great work, as usual!

I’m with you:

– we emphasize hip rotation as the primary driver in our dynamic rotary training exercises. I cover that in this video: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DIK3IHct0fY . I also, touch on it in the video you posted.

– since the body is an integrated until, we emphasize all joints working together to to evenly distribute load across multiple segments.

It amuses me how the same folks who like to say “train movements, not muscles”, turn around and talk about ” isolating the T-spine when performing rotary exercises.

– the general rule of joints is don;t over use them and avoid high loads and end ranges as much as possible. Do this and you’re doing all you active can to spare your spine and other joints.

That said, if all you do is twist from your T-spine, you’re certainly more likely to cause damage.

– We rotate the lumbar spine using low load mobility exercises, but with high load strength exercises. We do this based on the old saying “if you don;t use it, you lose it!”.

Plus, unless you’re healing from a major injury – There’s NO part of our body that will improve it function by NOT moving.

– Here’s an interesting tid bit to think about – If some one loses 1/3 of their ROM in any given joint, they’ve lost a significant amount of functional ability in that area. Now, if you lose 1 degree of lumbar ROM (each vertebrae has 3 degrees at normal), then you’ve lost 1/3 of the ROM you’re spine needs and was designed to have. Common sense tells us that, if we want to keep that ROM, we much regularly use it.

It’s just like what Gray Cook says about the squat pattern – we lose the squat pattern because we don’t use it. The philosophy behind the FMS is to regain the movement ability we all had when we were young.

If we use that logic, and I certainly do, than you have to apply it to EVRY part of the body! So, we use lumbar rotary mobility training (low load) to simply regain the lumbar rotation ROM we all had, when we were kids.

Keep on doing your thing bro!

Coach N

Nick, you and I have nearly the same views on this topic. Thanks for the comment buddy, and you keep doing your thing too.

Thanks Bret – Just realized I needed to correct something above. I mean’t to say: “We only rotate the lumbar spine using low load mobility (yoga type) exercises. But NOT with high load strength/power type exercises.”

The last time I spoke at Boyle’s, I demonstrated a very safe, low load lumbar rotation movement that we’ve been using lately with zero negative effects. It’s on video at BodyByBoyle.com

I’m not sure if Mike was on board with it. But, it’s something we’ve recently began incorporating after I had the realization that we may have over-reacted to this lumbar spine must be stable thing. My realization was “stabile” doesn’t mean “never move”. Rather it means “move less” than other areas around it. That is, in normal, everyday function.

Coach N

Nice Post, Brett.

I think there is some evidence for spinal rotations with ‘loading’ to cause damage to spinal structures, especially simultaneous bending and twisting. So I would keep it to a minimum.

BUT I think we are conveniently ignoring all those people who have gross spinal damages with no pain whatsoever. People who say they don’t do rotations for the fear of damage should MRI their spine. Might find some ‘surprising’ results.

I think strength training industry should be careful referring Shirley Sahrmann for everything we do. She came with whole “movement impairment syndromes” for treating people in chronic pain. She is one of those people who had to explain pain when we knew very little about the nervous system and pain. And hence everything she talks about will be based on a structural pathology model. This a great way to heighten the threat level and bring pain.

Great thoughts Anoop. I agree that bending and twisting is unwise and should be extremely limited (and probably never performed). I’m a fan of many of Sahrmann’s thought-processes but of course we need to consider the nervous system’s role in chronic pain. Thanks bud!

Hey Bret,

Great Post!

What i respect the most about your work (apart from the great content) is how you present your understanding of the ‘truth’ without creating conflict or judgement

Each article is written with the intention to both educate and stimulate thought – not to be a vehicle to launch your ‘ego’ and validate your own sense of importance

You are one of the true teachers out there my friend!

Keep up the great work 🙂

Oh and it is Mar(k) not Mar(c)

Agreed.

And how many fitness professionals think about going to Newzealand and getting their Ph.D? I think that just shows your burning desire to learn and improve in your profession.

Don’t let him fool you Anoop. The kicked him out for his unrelenting ass grabbing. 🙂

That’s a hell of a compliment Mark! And sorry about the name mispelling – it’s fixed. You keep up the great work too my friend.

Hey Bret, I’m not experienced enough to talk about what should or shouldn’t be done, but I very much agree with what Nick Tuminiello says and I implement many of Cressey’s drills in my own and my clients’ training.

I would, however, like to bring your attention to a great exercise that I learnt from Mark Young. It’s modified from the Russian Twist and it’s what I usually put in my non-beginner clients’ programmes when they want to “work their obliques more”.

http://www.youtube.com/user/MarkYoungTraining#p/search/0/hxW9ipPTVnk

Also, related to this, would you ever put core training before your lifting work, like what Alwyn Cosgrove programmes in his New Rules of Lifting For Abs?

I just think we are putting too much emphasis on damage, but our end point is always pain. If we think all our advice is to prevent herniations and degeneration, we should have our clients MRI scanned before and after.

If we are going by pain, and that’s what we always do, we should understand that pain do not correlate with damage most of the time. And hence we should focus on pain and not damage.

There are people who have really screwed up their spine that they would be good candidates for surgery right way, but they had no pain whatsoever.So all this talk about the degrees of rotation I feel is not really ‘clinically significant’. There is some common sense to limit too much bending and rotation with load, but beyond that..

Anoop, I’ve been thinking about the same issues (damage vs. pain) for quite some time, and I actually had a great conversation with Brad Schoenfeld about this. His insight led me to form the following conclusion. If we jack up the discs, etc., then the biomechanics of the spine can change, which may lead to subsequent injury and/or pain as a chain reaction. So it’s always of best interest to keep the spine as healthy as possible. Of course we want to raise physical capacity with our clients/athletes, but we also want to keep their spines (and all joints for that matter) as healthy as possible regardless of the pain aspect. For example, if I gave you these two options, I’m sure you’d choose option number two:

1. Squat 400 lbs, deadlift 500 lbs, VJ 36 inches, 40yd 4.5 seconds, no back pain, jacked up discs

2. Squat 400 lbs, deadlift 500 lbs, VJ 36 inches, 40yd 4.5 seconds, no back pain, healthy discs

Guy number one might not have any pain now but might develop pain down the road due to subsequent deteriorate- he could start developing endplate, vertebral, facet joint, spinal canal issues, etc. The spine seems to be very unstable in this way.

As to how to keep the spine as healthy as possible, now that’s a whole other story!

Do people who have abnormal scans develop low back pain in the future? Good question, but this has been studied since the 1970’s. There are a lot of longitudinal studies done in normal, asymptomatic people which shows none of the findings predict future disk problems or back pain. We have pretty strong evidence to show that imaging findings have no predictive value for future low back pain or disability.

Ann Rheum Dis. 1991 Mar;50(3):158-61.

A longitudinal study of back pain and radiological changes in the lumbar spines of middle aged women. I. Clinical findings.

Eur Spine J. 1997;6(2):106-14.

The relationship between the magnetic resonance imaging appearance of the lumbar spine and low back pain, age and occupation in males

The value of magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine to predict low-back pain in asymptomatic subjects : a seven-year follow-up study

Most of these thought processes can only lead to pain catastrophisizing and anxiety which can increased the perceived threat level in the brain. It has been shown how education about spinal structures, discs, imaging, and spinal anatomy increase pain while education of the neurophysiology of pain decreases pain scores.

Is there a common sense in saying didn’t do stupid stufff like deadlifting with rounded low back? Yes. Is there any reason worrying about the 5 degree changes in rotation and how it affects the disc and such? No.

Anoop, great thoughts. Any chance you have a link re: the education of spinal structures/neurophysiology and pain? That’s huge.

Here is the one:A randomized controlled trial of intensive neurophysiology education in chronic low back pain.

Discographic, MRI and psychosocial determinants of low back pain disability and remission: a prospective study in subjects with benign persistent back pain. Another study which shows psychosocial variables to strongly predict back pain than structural changes seen in imaging.

From what the research shows we need to limit all this biomechanical talk .I think there is some wisdom of limiting certain movements which can cause acute injury. But by emphasizing more of the structural problems in low back, you are just setting themselves up for pain ( by raising the threat level ). The evidence is not there to show that structural abnormalities predict or cause pain though we have been studying this for years.

Here is post which talks about the same: http://bodyinmind.org/spinal-mri-and-back-pain/ here is post which talks about the same.

anyway, great post!

Thanks Anoop – very interesting blogpost. I’ve often wondered if the more you educate someone on spinal structures, forces on the spine, degenerative changes, etc., the more they’ll start developing fear, anxiety, and pain.

We have biomechanical evidence that certain movements are dangerous for the spine, but in my experience as long as you pay close attention to form, intensity, frequency, and volume, athletes and clients can do many movements pain free (and they might even be beneficial to spinal health). So I’m not quick to throw a certain exercise out the window – I just try to follow certain rules.

The Nick Tumminello video is quite an eye opener, pretty scary actually.

Awesome read as always. Very thought provoking

I agree with both Bret and Nick. I would say that it really depends on the needs of the person that you are working with. From my experience my clients have so much going on mentally that just getting them to activate the core and attempt to keep it stable is a big enough task. I really make sure that they can resist movement, then and only then will i add rotational work. If you watch a lot of people perform rotational work it looks to me as if they are just heaving the weight around and the intended muscles are not receiving any work. Just my thoughts i could be way off though. Awesome article thanks for all the great stuff

Bret, epic post … again!

Lately much attention has been given to the role of the thoracic spine as a crossroad of shoulders, neck, lumbosacral segment and less attention has been given to the thoracic spine itself. You provide facts, context and solutions. It’s really important, because we actually know squat about the thoracic spine.

First of all, we really don’t even know the range of motion. Most cited data comes from Panjabi 1978, which is actually an extrapolation of a single cadaver study (White 1969). Other extrapolations like Grieve 1991 or Mercer 2004, also based on the White study, conflict with these estimates. We should also separate the lower (T10-T12) and the upper thoracic spine in movement properties and in disc morphology (Mercer 2004). The thoracic disc seem to be different than it’s lumbar counterpart. Prevalence of thoracic spine pain is relatively low, but annulus tears symptoms are described as a band-like pain in the chest area. With different morphologies of the thoracic discs, any comparison with the lumbar spine would be invalid.

It’s true that damage in de lumbar discs, established by discography or by lying in a MRI, does not correlate well with symptoms. CT-scan with pain provocation and MRI with barium sulphate as a contrast fluid however, seem to correlate well. We can therefor not assume that damage has no link with symptoms in the lumbar spine. Not only do we have to take into account the imaging technique, we also have to consider the location of damage (near nerve endings) and whether there has been any nerve growth. The main message is that we cannot dismiss disc damage, due to convenient, but imperfect imaging technology.

Bulging discs form rotation only, seems to be unlikely (Marshall LW 2010) and we have about 4 degrees rotation in the lumbar spine during gait. Some rotation from this area seems reasonable, although we have no idea what it means when we do loaded rotations. Rotation does seem to delaminate the disc (Marshal MW 2010). I consider adding rotation from the lumbar spine to spread the load is a very smart proposition. Loaded rotation from the lumbar spine instead of the thoracic spine, however, will increase the lever and therefore increase compression (while delaminating the disc). And while rotation is correlated with higher risk of low back pain, rotation (damage) from the thoracic spine appears to be mostly asymptomatic. Because we cannot determine or influence the quality of the discs, which is mainly genetically determined, I believe we should be careful, because we have no clinical tool to assess the quality of the discs of our clients.

To answer your question. Without proper knowledge and evidence of the thoracic discs and spine, we can only revert back to epidemiology and biomechanical reasoning. Considering all of the above and the low prevalence of symptoms in the thoracic spine, I believe I would choose to limit lumbar rotation.

Thanks a million for bringing up the subject. Keep pushing!

Great article. Definitely a topic that needs addressing.

With the knowledge that disc degeneration has a huge genetic component, would you consider using spinal extension stretching(ie McKenzie exercises) prior to heavier lifting? With lumbar extension stretching you get multiple discal effects: anterior migration of the nucleus, decreased overall discal pressure, increase in anterior fluid volume in the disc with decreased posterior fluid volume. Discs tend to become very symptomatic when they bulge far enough posteriorly (especially if they contact the neural structures). If posterior pressures can be reduced pre and post heavy lifting it seems the degenerated disc would have less chance of becoming symptomatic.

I am speaking out of experinces with my own back. Playing rugby for 12 years at 2nd row(hopefully you now know what position this is and the stresses that occur) resulted in 3 HNPS (2 with extrusions) confirmed by MRI. I still am able to lift regularly but I am limited with the loads I can use for squats, DLs, etc. For the last few years I have followed a protocol of 10-20 pressups pre and post workout plus a few additional sets during the workout if I am doing heavier lower body lifts. I feel that using this system has kept my symptoms at a minimal.

With clients or patients we really don’t know if they have degeneration that is just waiting to occur. If spending a few minutes doing extension stretching in the warm-up could reduce the change of this occurrence then it would be very much worthwhile.

I am very interested to here your thoughts on this.

Thanks for everything. Your information is priceless.

Hey Kevin, thanks bud. Here are my thoughts:

1. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. Meaning, if you’ve found something that seems to work, and it’s helping you continue to lift, then don’t second-guess it.

2. Obviously many individuals with extension-based spine issues would find this practice problematic, but I believe that many individuals would benefit from balancing out the flexion-related stuff they do with extension-related stuff.

3. I haven’t thought much about where I’d program this in…but I think post-workout makes the most sense. Pre and peri workout might bring some negative creep-related issues to the table which could negatively impact performance and/or spinal biomechanics, but post-workout you’d theoretically mitigate flexion-based posterior nuclear migration and normalize the discs right away.

Great post Bret!

Awesome points on rotation. I with you on all your points. Thanks for the great videos.

As far as getting more thoracic mobility I like to start with this drill

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aCEKBGRhSBQ

and then work to the seated one that Mike does in the video above.

Also, I’ve started to use this Hip IR drill with some of my rotational athletes and seen some great improvement pretty quickly. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-o2i5UAeJaY

Keep pumping out the great content. Hope NZ is treating you well!

Thanks for the post Kevin. I would have shared those excellent links you posted had I know about them. Keep up the great work my friend.

Bret,

Assuming adequate flexibility/mobility and proper instruction, how do you feel about the windmill exercise as both a hip mobilizer and “core” exercise?

Erik – I’m not afraid of the windmill exercise. I just wouldn’t do it too frequently (2x/week) and I’d rotate it in and out throughout the year. Of course, it depends on the client, goal, etc. -Bret

I couldn’t reply to your post. No reply button. Did u disable because I was writing too much or what (:-

That’s a great blog from Moseley. That’s very true what you said. And that’s what I ‘tried’ to convey in my pain article. Atleast from the current research, one of the the major factors which turn acute pan to chronic pain is the fear avoidance beliefs in the patient. Imagine saying rotation, bending is bad for you and such with all the pictures and such and how our clients will not have fear of movements?

Anoop, I think it disables replies after a certain amount because there isn’t enough room for it to show up as each reply gets shifted to the right. Of course I’d never disable you!

I thought so. I was just joking about you disabling it.

Hi Brett,

Nice post, like the way you have referenced articles instead of just philosophizing, which you see a lot on peoples sites.

One thing I would like to make more of a point is the role that the lower body plays in rotation training. You quoted Mark Buckley’s article, from memory he talks about the integration of lower body load transfer as the key to good rotation training. So from a practical point of view after ROM is assessed as adequate, the best way to train any rotational movement is to first generate force from the ground up (which is exactly what happens in sports) and or transfer the load from leg to leg (e.g like passing a ball, or throwing a javelin). A great place to start is a simple step out and back lateral lunge (no additional load).

Great topic, look forward to your next blog!

Regards

Michael

This post really has changed the way I exercise – a serious amount of anti-rotational work has been missing from my work for too long!

Thank you!

Bret, I hope it isn’t too late to ask a question on this post.

I came across an interview in which a gentlemen stated Mel Siff showed him research that the snatch is the best way to train rotation because it requires a lot of counter-rotation.

It’s on page 4 here: http://posturalsportsperformance.com/Secrets-to-Developing-Rotational-Strength.pdf

I was wondering if there was any truth to this, as I don’t see how the transverse plane is in anyway involved with the snatch/overhead squat.

Thanks

My AD (I’m a HS S/C) informed me we were getting a used Cybex rotary torso machine after she and I had a lengthy conversation about its dangers, but since it’s a “poular” machine she thought we should have it. Is there any research articles as to the dangers of of this fixed hip, lumbar rotation torture device? If so please let me know.

Thanks,

Rob Izsa, MA, CSCS, USAW

Rob, I’ve read something on this in the past month but I can’t find where I read it. You could send her a link to Nick’s video. That said, you can make it safer by keeping it within tolerable ranges of motion. A brand new study http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21343864 indicates that short range torsion is good for the discs. Maybe you could have them do some short range pulsing. -Bret

Thanks for the info. Keep up the good work!

Rob

Hey Bret, great article!

I have a question maybe you can help me out. I was peforming bent over rows at about 45degree angle 275lbs for 4×6 reps, 2 min break. Keept a nice neutral spine throughtout. The third set 5th rep as I lowered the weight my lower lumbar popped on the right side. I couldnt really walk, sit, just crawl and lay down. After 3 days of mostly laying down, and a few sharp pains, couldnt really get down in my bed or tie my shoe. after a week no pain at all, and its been 3 weeks with no pain.

The MRI I received said I had a l5-s1 paracentral annular tear with mild facet arthopathy. mild disc space narrowing with small marginal spurs,

l4-l5mild facet arthopathy a bulge

Should I avoid Deadlifts, squats, any shrugs that will cause compressive force? Forever? i am a ifbb pro professional athlete. dont want my career to be finished.

Chad