Knee valgus is a very common occurrence in the weight room. It’s also common in sports. Hell, you can even go to a public place and examine people’s walking form and detect knee valgus in a minority of individuals. In this blogpost, I am going to teach you all about knee valgus and how to go about correcting it.

What is Knee Valgus?

Knee valgus is also referred to as valgus collapse and medial knee displacement. It is characterized by hip adduction and hip internal rotation, usually when in a hips-flexed position (the knee actually abducts and externally rotates). It can also be thought of as knee caving as you sink down into a squat or landing. When standing on one limb, the opposite side pelvis will usually drop during valgus collapse as well.

Why is Knee Valgus Dangerous?

Knee valgus can lead to patellofemoral (knee) pain, ACL tears, and iliotibial band syndrome. It can also lead to ugly squat syndrome.

When Does Knee Valgus Typically Occur?

Knee valgus most commonly occurs during upright ground-based activities that require eccentric action of the hip extensors. Essentially, gravity acting on the body induces large adduction and internal rotation torques on the hips while the hips move into flexion. The hips must absorb and reverse the sagittal plane flexion torque while stabilizing the femur in the frontal and transverse planes so the knees track over the toes. For many individuals, this is easier said than done.

You’ll commonly see valgus collapse rearing its ugly head during squatting, lunging, jumping, landing, climbing and descending stairs, and even during gait/running.

While you won’t see many instances of knee valgus during hip-hinging motions such as conventional deadlifts or good mornings, it does occur on occasion. I’ve actually trained a few clients that were so weak and deconditioned that their knees caved inward when performing a body-weight Romanian deadlift (simple hip hinge task with no load). This is rare, and it typically occurs with individuals who experienced a lower body injury and never rehabilitated it properly. You won’t see knee valgus occur very often during hip thrusts either, but if you do it’s much more easily correctable compared to knee valgus during squatting due to the lesser adduction/internal rotation torques and lesser hip flexion ROM.

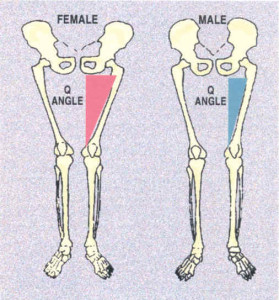

Are Women More Prone to Exhibiting Knee Valgus?

Yes. Women are more prone to experiencing knee valgus due to their proportionately wider hips, increased Q-angles, diminished hip strength, and in my opinion from being taught to “sit like a lady” (along with reinforcing that movement pattern repeatedly throughout their lives).

Why Does Knee Valgus Occur?

As to what’s causing the valgus collapse, in the research it has been suggested that knee valgus can be caused by four primary fixable factors. I’ve arrange them in order of most likely to least likely, based on my informed opinion:

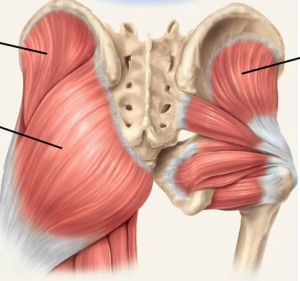

1. Weak Hips

Inadequate gluteal/hip strength (gluteus minimus, glute medius, gluteus maximus, hip external rotators), possibly in conjunction with overactive hip adductors, prevents proper stabilization of the femur. The hips then move into adduction and internal rotation. And when the adductors are overactive in comparison to the glutes/hip external rotators, the knee is similarly pulled into valgus collapse.

2. Tight Ankles

Inadequate ankle dorsiflexion mobility along with tight lower leg musculature (gastrocnemius, soleus, and anterior tibialis) prevents the tibia/knee from migrating forward sufficiently. This causes the foot to compensate by pronating (allowing for more forward knee migration), forcing the tibia to internally rotate, which leads to hip internal rotation and hip adduction, and therefore knee valgus.

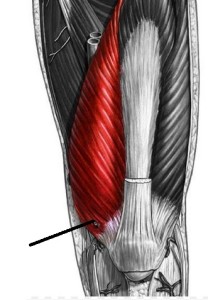

3. Impaired Quad Function

Inadequate VMO (vastus medialis obliquus) strength will fail to allow for proper knee stabilization, which will cause the knee to track inward.

4. Impaired Hamstring Function

Inadequate medial hamstrings (semimembranosus and semitendinosus) strength will prevent proper stabilization of the knee which will lead to some medial knee displacement, similar to what happens with impaired VMO function but on the opposite side of the thigh.

Knee valgus could initiate from a combination of these factors, but once it “sets-in,” it becomes a brain/nerve problem and not just a strength or flexibility problem. Therefore you’ll always have to re-groove squat patterns even when restoring impairments or imbalances.

Are There Any Other Reasons that Could Influence the Knees to Cave When Lifting?

Yes. It’s been suggested in the research that knee valgus could occur for purposes of mechanical advantage. Specifically the gluteus medius loses all of its leverage (called a “moment arm” in sports science) as a hip abductor at the bottom of a squat. However, if the hip is internally rotated, the gluteus medius regains some of its leverage as a hip abductor. However, this same hip internal rotation at the bottom of a squat would cause the gluteus maximus to lose some of its leverage as a hip extensor, so it would be a slight trade-off. When maxing out or repping to failure, the body will take the path of least resistance, so this might explain the tendency to want to cave in at the knees. However, this is yet to be thoroughly examined in the literature.

Anatomy also plays a considerable role in contributing to knee valgus. Pelvic width, acetabulum shape, femur shape, knee shape, tibia shape, ankle shape, foot shape, ligament laxity, along with tendon attachment points for hip and lower body muscles, can all influence the likelihood of knee valgus occurrence. Some individuals are much more prone to exhibiting valgus collapse than others based on their anatomy.

Is Knee Valgus Occurrence Always Due to Deficits in Mobility or Stability?

As mentioned above, knee valgus is often due to insufficient hip strength or inadequate ankle mobility. However, knee valgus can also be due to faulty motor patterning. Many lifters simply learned to squat that way and just don’t know any better as they’ve never been taught proper form. They might have all the stability and mobility needed to squat properly, but they just require proper coaching and practice.

What’s the First Step in Correcting Knee Valgus?

First, you must determine if the issue is due to deficits in:

- Ankle Dorsiflexion Mobility,

- Hip Stability, or

- Coordination

How do I Know if the Knee Valgus is Due to Insufficient Ankle Dorsiflexion ROM?

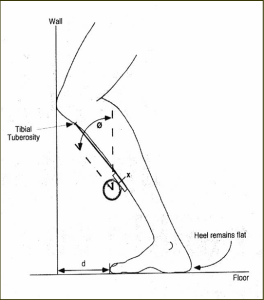

Test the box squat to parallel depth (or slightly lower) and examine ankle dorsiflexion mobility in a half-kneeling position.

If box squats are performed properly (with no knee valgus), but the knee moves into valgus when performing full squats, then this is a good clue that knee valgus is occurring due to ankle dorsiflexion deficits. Moreover, if the foot heavily pronates during the full squat, this is another good clue that inadquate dorsiflexion mobility is the culprit.

You can also test ankle dorsiflexion ROM from a half-kneeling position to determine how much functional ankle dorsiflexion ROM an individual possesses. I prefer testing weight-bearing positions rather than non weight-bearing positions as 1) individuals have much more ROM during weight-bearing, and 2) weight-bearing is characteristic of the squat and other functional positions, so it’s more specific to what you’re trying to improve.

In the video below, you’ll see the individual performing an ankle mobility drill with a dowel. Placing the dowel on the outside of the foot and ensuring that the knee still tracks outside of the foot is ideal as this prevents foot pronation so you get a good estimation of one’s true ankle dorsiflexion ROM.

Make sure the heel stays flat and the foot doesn’t pronate. To determine your functional ankle dorsiflexion ROM, perform the drill above and pause at end-range. Take a snap-shot from the side view or measure with a goniometer to determine the angle. Perform this barefoot.

How Much Ankle Dorsiflexion ROM is Normal, and What’s Needed in a Squat?

This depends on the anthropometry of the lifter and the type of squat being performed. It also depends on the shoe being worn. Olympic weightlifting shoes have high heels on them, and this greatly increases the potential for the knee to migrate forward and the tibia to form a more acute angle relative to the ground. For testing purposes, I recommend being barefoot.

Normal ankle dorsiflexion ROM under weightbearing is 7-35 degrees, according to THIS study. Different types of squats and body types require varying levels of ankle dorsiflexion. A full squat requires considerable ankle dorsiflexion. A full squat with an upright torso requires even more (sometimes over 45 degrees). Alternatively, a high box squat doesn’t require any ankle dorsiflexion (0 degrees), especially when you sit back properly. In fact, in THIS article, Louie Simmons mentions that you can sit back so far in a box squat that you surpass a vertical tibia, which would create slight plantarflexion.

Sure she’s wearing Olympic shoes, but this is still some serious ankle dorsiflexion – around 45 degrees. Still, it’s not enough for this upright of a squat. Notice the foot pronation and subsequent internal rotation of the tibia and hip.

However, only around 10 degrees of ankle dorsiflexion is required for the same lifter with this type of squat.

If a lifter lacks the required ankle dorsiflexion ROM to perform a particular style of squat, in order to reach depth they will either:

- Round their spine,

- Rise up onto the balls of their feet, or

- Pronate their feet (which leads to knee valgus).

For these lifters, corrective ankle dorsiflexion mobility drills and calf stretches are imperative. I’ll teach you some great drills and stretches for this purpose later in this article.

How Does Foot Pronation Help Achieve Greater Forward Knee Migration?

Think of the toe-touch or the sit-and-reach test. You think you’re testing hamstring flexibility, but really you’re getting a combination of spinal, pelvis, and hip range of motion. If you want true hamstring flexibility, then neutral spine and pelvic postures must be employed, which dramatically reduces the total ROM.

In the same manner, you get more ROM when the ankle dorsiflexes and the foot pronates compared to ankle dorsiflexion alone. Here is a picture of my ankle dorsiflexion ROM compared to my combined ankle dorsiflexion and foot pronation ROM. Notice I get around 10-15 degrees more ROM with the foot pronated.

This is why many lifters pronate – to get more ROM to allow for greater squat depths. This is not ideal though and it’s akin to allowing for spinal flexion to compensate for insufficient hip flexion mobility/hamstring flexibility in a deadlift. Sure it’ll get the job done, but it the process it can wreak havoc on the body.

How do I Know if the Knee Valgus is Due to Insufficient Hip Stability?

Either have a partner/coach create “artificial hip stability” by forcing the knees out for the lifter while the lifter descends in the squat, or squat in front of a pole and hold onto it for stability. If proper squat position can be reached, with proper foot supination, proper ankle dorsiflexion, proper knee tracking, and a realistic torso angle that’s similar to real squatting, then this is a big clue that the issue is related to inadequate hip stability.

If good squat position can be reached with a little assistance, then the lifter just needs to bring his/her hip stability up to par. I will discuss the best corrective exercises for this purpose later in the article.

How do I Know if the Knee Valgus is Due to Lack of Coordination?

This one is simple. If the issue is a matter of coordination and lack of knowledge of technical form, then within approximately five minutes of coaching and practice, the lifter will be able to perform a proper bodyweight squat with proper knee tracking (no knee valgus). Surprisingly, this works on a fair amount of beginners – they just need to learn what good squat form is supposed to look and feel like.

If I Bring an Individual’s Hip Strength or Ankle Mobility Up to Speed, Does This Automatically Fix Their Knee Valgus?

No, it doesn’t. Studies show that strength training alone can indeed improve knee valgus, as can motor re-education. However, you need both strength and technique work for maximum results in the quickest amount of time. Neither strategy alone will achieve this – both are needed.

Case in point – you can usually strengthen the heck out of a lifter’s glutes with hip thrusts and band walking exercises, or you can stretch/mobilize someone’s calves/ankles repeatedly over a couple of months, yet this does not automatically fix their valgus collapse when squatting.

At the end of the day, if you want to correct knee valgus, even after you’ve restored ankle mobility and/or hip stability deficits, you have to lighten up the load and re-learn how to squat with the knees tracking over the toes.

In fact, you can even squat with the knees slightly outside of the toes which is called knee varus – the opposite of valgus. Click on the link to Simple Squat Correction for a video and blogpost on the concept of slight knee varus during the squat.

How Long Does it Take to Fix Knee Valgus?

I’ve had clients clean up their form within 5 minutes and others who took 3 months to correct when using heavy loads, depending on the circumstances. However, one quality session doesn’t insure that solid performance is “locked-in.”

Motor re-programming takes time and requires persistence. It has been suggested that a motor engram (memorized movement pattern) requires thousands of repetitions of proper performance to become ingrained. Obviously there are some who learn more quickly than others due to increased kinaesthetic awareness, but hopefully you catch the drift as to how much work is required for automaticity to be reached.

Lifters need to get to a point where they don’t have to think “knees out,” it just happens automatically.

You might be strong at squatting with your legs aimed forward, but you need to get strong and accustomed to squatting with the legs angled outward.

So it’s Mostly Beginners who Fall Prey to Knee Valgus?

Not always. The majority of newbies do indeed exhibit knee valgus when they squat. But often experienced lifters can squat just fine until reps are pushed to failure or loads approach 1RM. When pushing it to the limit, they often cave inward a bit at the knees. This means that their bodies can control knee tracking just fine unless the system is pushed to the limit.

In fact, many Olympic weightlifters, powerlifters, and strongmen exhibit knee valgus when squatting heavy – are you going to tell them that they all have weak glutes?

Many Olympic lifters exhibit what I call a “Valgus Twitch” when they squat. They initiate the concentric portion of the squat with the knees out, and then at the sticky region the knees migrate inward, and finally they travel back outward after the passing of the sticky region. See the video below for some examples.

What are Energy Leaks and Why Should I Care?

Energy leaks are eccentric contractions due to the neuromuscular system’s inability to maintain a static hold. Are all cases of energy leaks the same? Not really. There’s a difference between a newbie collapsing at the knees because he/she has dysfunctional ankles or hips and a 500 pound squatter allowing for some controlled medial knee displacement. The 500 pound squatter could easily keep his knees tracking perfectly over the toes when using 400 pounds (80% of his 1RM), but when maxing out he will allow for some wiggle room.

For safety purposes, you want to limit the energy leaks to strategic periods of time (competitions or testing your max). Most of the time in training, you want to use strict form. By preventing knee valgus, you’ll ensure that the load on the knees are distributed evenly so that the lateral aspects of the knee joint is protected. This will allow you to train pain and injury free so that you can continue to build up your strength indefinitely.

Is Technique Work and Motor Re-Education Your Best Bet for Correcting Knee Valgus?

Yes, but not always. As I mentioned earlier, if knee valgus is occurring due to deficits in mobility or stability, then it’s best to perform special corrective exercises in order to bring the lifter up to speed in the quickest amount of time. However, motor control training can indeed build mobility and stability, albeit at a slower pace.

When practicing proper technique work, you end up strengthening the muscles that need strengthening and stretching the muscles that need stretching, all while increasing coordination and grooving proper firing patterns.

If the issue is indeed purely motor control related, discipline is required. All good lifters love going heavy and pushing the body to the limits in training. Similar to rounding of the back when deadlifting, the solution to preventing poor form often involves building up the discipline to limit the loading when form starts to erode or calling it quits before true muscular failure ensues. Some slight flexion of the spine when pulling heavy loads is tolerable, as is some slight knee valgus when squatting heavy loads. But too much will be injurious to the spine and knees. Good lifters learn and know their limits.

What are the Various Strategies to Correct Knee Valgus?

The following are what I believe to be the best strategies:

1. Ankle Dorsiflexion Mobility Drills and Gastroc/Soleus Stretching

If a lifter has poor ankle dorsiflexion ROM and tight calves, then this needs to be addressed. Otherwise knee valgus during full squats will not be preventable unless the lifter wears Olympic shoes or elevates the heels onto plates.

Both mobility drills and static stretches have been shown to be effective in the research for improving ankle dorsiflexion mobility. I believe that both should be utilized for the most rapid results.

Physical therapists often utilize bands and straps to increase the effectiveness of the drills, but good results can be realized from basic maneuvers as well. Here are few drills that you may want to employ:

2. Motor Re-Education With Immediate Video Feedback

As mentioned above, motor control training and technique work give you the biggest bang for your buck. Start with bodyweight loading. then move to goblet squats, and then on to barbell loading. Actually, it may behoove you to start with less than bodyweight loading and perform assisted squats via bands, cables, suspension systems, or poles (as I showed in the picture above).

Below is an effective manner of performing kettlebell goblet squats. These can also be performed with a dumbbell by holding it vertically and placing the palms on the underside of the top plate. I recommend doing these barefoot and concentrating on keeping your weight on the lateral edges of the feet to improve foot supination habits.

One of the best strategies I have for fixing valgus collapse is to film the lifter and play back their video clips immediately after the set. I did this with my client Karli for six straight weeks and it cleared up a nasty case of knee valgus. See videos of her form after this process HERE. You’d have never known that a few months prior to this she had one of the worst cases of knee valgus I’d ever seen.

3. Mini-Band Exercises

In my opinion, the only two exercises that are really worth doing in this category are mini-band squats and mini-band bridges or hip thrusts.

I’ve found that ideal band placement for these two exercises is just below the kneecap, as this position prevents the bands from sliding upwards on the thigh during the set.

Do not use heavy weight with these exercises! Do them with just bodyweight or with light loads. If you try to go heavy, your form won’t look very good and you won’t be able to use anywhere near your maximal weight. The purpose of these is to help teach the body which muscles force the knees out during the squat and build some hip abduction/external rotation strength throughout the hip flexion-extension range of motion. Essentially, you’re blending together hip abduction, external rotation, and extension strength. If you want to push the envelope on these joint actions, perform specific exercises for each action. But banded squats and bridges are more about activation and quality, not quantity.

4. Hip Abductor/External Rotation Exercises

This category includes x-band walks, monster walks, sumo walks, band seated abductions, band/cable standing abduction, side planks, Pallof presses, band anti-rotation holds, and band hip rotations.

Click HERE to see a video on ideal placement for band walking exercises (spoiler: foot placement trumps ankle and knee placement).

I like the band seated hip abduction, but bear in mind that this just builds hip abduction strength at this particular range of hip flexion. I recommend performing 3 sets of this – one set below parallel, one set at parallel, and one set above parallel. Notice the placement of the band – right below the knees.

Why Aren’t Band Walking Drills Ideal for Correcting Knee Valgus in a Squat?

Most often lifters cave more toward the bottom of a squat, not right out of the gates. Band walking drills strengthen the hips in an upright fashion, in a more neutral hip position. This builds more frontal plane strength. However, knee caving in a squat is often more of a transverse plane situation, and the hips need to be strengthened in a deeper flexed position.

I’m definitely not saying that they can’t help, I’m just providing you with something to consider. I recommend performing band walking drills in a crouched position as well to target more flexed ranges of hip abduction/external rotation strength.

Conclusion

That about wraps things up. I hope you’ve enjoyed this article on knee valgus (valgus collapse) and have learned a thing or two on the topic. Proper squat form requires sufficient ankle dorsiflexion, glute activation, hip stability, motor control, and discipline. If you suffer from ugly squat syndrome, you’re not plagued with this for life. Employ the recommendations in this article and clean it up. Your knees will thank you later!

I have knee valgus all the time. I can’t stand at attention w/o bending my knees a little b/c they bump into each other. It has been like this since I was 2-3 years old. While it has gotten better since I started strength training, it is still there. I am relatively strong, Squatting 350 for 5×5 with good form. Would the tips in this article still help my case me?

Andrew – is it a skeletal deformity? If not, then I’m sure it can improve if you focus on it. But if it doesn’t cause pain, then don’t obsess over it. Sounds like your case is pretty bad though! I’d like to see a video of your form.

Good call Brett, excessive femoral torsion is a boney deformity and is easily differentiated by a good Osteo or PT. But most of the time it is weakness or poor motor control of the hip leading to valgus collapse.

Dear Bret, happy to read your article about valgus knee. 11months after getting operated for Acl tear in left knee, I started playing badminton again but unfortunately after 2 months got mild valgus in right knee (non operated). Please help me out what to do?

great article, really useful tips. question about this point “You might be strong at squatting with your legs aimed forward, but you need to get strong and accustomed to squatting with the legs angled outward.” why is that? are we not losing torque by externally rotating? ive always tried to move from the 30-35 degree toe out position to a more forward position, ive found my sweet spot at about 10-15 degrees as i have a restriction on my right ankle (self diagnosed from this mwod video http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q3UGl2rHz18 ). but just curious why you would advocate squatting toes out if you can already squat strongly with toes forward (and avoid excess knee valgus)?

Jeremy – I didn’t mean that you have to turn the feet out. I meant the legs out. I didn’t watch the video you posted but if it’s from Kelly Starrett I’m aware that he recommends squatting with feet forward but legs flared out as well. I do agree that this approach can work well for many, I feel that most do best with around a 20 degree foot flare. However, this is highly influenced by anatomy. So if 10-15 works best for you, stick with that!

misinterpreted the difference between foot and leg, thanks for the reply.

Hey great article I find all of your article really useful. In fact yesterday I was teaching and student after student had valgus knee so this really helped.

Hi Bret, very interesting info as always, you mention weak VMO can cause problems with valgus collapse, I am pretty experience at squating etc & my technique is good, my question is, I suffered two rupture patella tendons playing football a couple of years ago…..since then I’m working hard to build my legs up….however I’m having issues with my VMO’s, I’m not getting any hyperthropy in them, can you recommend a good isolated exercise to achieve growth, thanks for your attention,

Cheers Ollie!!!!

Hi Bret!

Involves the proper alignment of the spine, especially dorsal spinal erectors to not rotate the pelvis and thus influence the valgus knee.

Thanks.

Hi Bret,

What a coincidence you post this article yesterday as I was working with a client with knee valgus. He’s an ice hockey goalie, so his position when he’s playing put him at risk. There is some very good point like ankle mobility. I’ll be sure to check that with him today.

I’m sorry, I forgot mensionarte I follow all your tips gluteal activation but not if ue so I said before the erector spinae activate not quite a full rom.

thanks again

Hi Bret! Great article. Funny thing is i`ve a skeletal deformity, genu varum, and never found info about this. My knees goes out automatically in a squat, deep jump, hip thrust, etc. Do you have clients with a problem like this??

I didnt see a strategy for correcting the potential hamstring imbalance. Did i miss it?

With squats being all the rage lately excellent post. I especially like the point about strengthening the hip abductors and external rotators in the specific point of weakness in the squat. Some of the hip external rotators become internal rotators as hip flexion increases. We’ve got to train for specificity! I feel this is an area that is lacking at times in the physical therapy world.

Being mobilitywod went to a pay site its nice to see you posting info. like this for free!!

I work with a lot of female athletes in different sports, and do many of these things. It’s great to see them all in a well researched article that makes it easy to understand. I will show this to coaches, who seem to be the biggest hurdle. Thank you.

Wonderful article Bret – as an Exercise Scientist in training I really appreciate your ability to take the anatomical and biomechanical concepts and explain them so effectively – this is a fantastic skill so keep it up! You are doing all your subscribers are great service so cheers!

Indeed!

Bret,

What if the issue is with the hip caving in and not the knees? I’m able to do full range body squats with no issues, but I can’t put more than 25lb plates on without my right hip caving in on the ascend (my hip caves but not my knees). I the same issue with single legged activities like step-ups, split squats, lunges, etc). I thought it was a balance issue, but I’m pretty sure it’s a muscle imbalance caused by my scoliosis. My right hip feels weak. What would you suggest I do? Thanks!

Excellent article. Perfect timing. I am working with a runner with the same issue and this is extremely helpful. Thank you for an well written article.

Bret, great article! Do you include foam rolling in your calf flexibility work? And what are your thoughts on adductors, quads, and/or ITB contributing to valgus knees?

Bret, How many people have you cured of knee valgus?.

I have focused more on my hips and glutes the last 3 months and my ROM has increased in my squat. I am able to go deeper and I have see a large increase in my sprinting. You always supply us with great info Bret keep it up.

Hey Bret,

I have pins and plates in one ankle from a bad break 6 years ago. Dorsiflexion is a problem, so I squat with a wide stance to lessen how much I need to put that knee straight over my ankle when descending. That said, my adductors and abductors are taking on extra work and feel tweaked if I go heavy (although no real valgus collapse). Do you still suggest these drills to help improve ankle ROM?

“Many Olympic lifters exhibit what I call a “Valgus Twitch” when they squat. ”

Bret,

I’d like to comment on what you are observing- In the very bottom position of the ATG squat, there is a tremedous side torque on the hips (I think maybe the adductors and glute medius). The only way to alleviate this is to allow the knees to track back in a little. I believe your “good pal” Poliquin has commented on this in several articles, as he he a proponent of ATG squats. I think the point I’m trying to make is that while in the very bottom position of the full squat, it is safer on the hips to allow the knees to cave a little, and not an indication of poor form or poor movement. I don’t think this is an issue for parallel squats or Rippletoe’s ‘very deep’ squats. What do you think? – thanks

Bret, You provided here one of my favourites articles. Thanks a lot (by the way, I’m surprise there are not more comments) .

Probably, and please correct me if you disagree, another way to say that standard crab walking is not efficient to fix knee valgus (when it comes to performe squats) is the fact that gluteus medius and minimus are lateral rotators when the hip is flexed but become medial rotators when the hip joint is extended. So, in order to make them effective, “crab” or “side walking bands” requires simultaneous and continues flexion of the hip and knees, which is the hardest stage of the squat and it’s when the knee valgus occur. Cheers. Will

Thanks Bret for the in depth information. I will begin to train a friend (my first client) this week and I noticed she has fair amount of valgus collapse when she quarter squats. I am glad I read this website so I don’t become the “bad trainer”, haha. Also, I began spotting another friend recently. She doesn’t go beyond parallel, and keeps her knees straight in front of her. The more weight she is adding to the bar, the more I have noticed some collapse. I am wondering, should I just ask her to start box squatting to show her keep the knees out? If so, should I start with a high box or to parallel? And how much more information should I give her since she is pretty flexible? She used to be a gymnast.

Thanks again Bret!

Hi Bret,

You wrote an article a while back talking about a guy whos’ medius was incredibly weak and part of the recommendation for him included bands and rotations at three different seat heights. I am having difficulty finding that article, do you know which one I’m talking about?

Thanks,

Don

Here’s the video: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uo4_wM5r7zY

Here’s the article: http://bretcontreras.com/repeated-adductor-strain-during-squats-a-case-study/

Thank you Brett, I’m very grateful!

I meant Bret!

My Genu Valgum is a skeletal deformity. Can it still be corrected using your techniques?

I have had knock knees since I was a child. I had rickets then. The deformity didn’t resolve, and I grew with them. Can I apply your techniques to my case?

I have a prosthetic, left leg below the knee. I’m an aspiring bodybuilder (5’8″, 178lbs even missing a leg, and 11% BF currently), and I just added squats into my routine. I’ve been having knee and anterior hip pain after squats. I had a friend take a video and sure enough, I’m leaning laterally towards the right side (my good side), pronating my ankle, and turning my knee in. I can see my body naturally reacting to get more leverage with my right leg by coming up and under the weight, distributing more to my good side. I do have an impressive calf muscle, but I can barely get my knee past my toes on the half-kneeling ankle dorsiflexion stretch. However, when I squat, I feel tremendous strain on my calcaneal tendon as well as my tibialis anterior, but not so much in my gactrocs. I just watched myself in the mirror doing supported pistol squats and the effect is even more severe. Knee buckles in, ankle pronates and my heel comes off hte ground by more than an inch. Even If I try,, I can’t stop it. If I don’t flex up onto my toes, I fall backwards and to the left before I get halfway down. What are your thoughts on this?

Incredible article. Very glad I found this. I’d been training a client who gets a valgus twitch at the bottom of heavy, below-parallel squats; otherwise her form is great until we get heavy and low. I’d been having her add abductor accessory work as well as wide leg presses to address abductor and VMO weakness, but after reading this article am realizing I am probably missing the biggest piece. She is shorter and heavy and so has incredible calves, and now a lightbulb is going off that her dorsiflexion is probably really tight. Thanks so much.

Do you mind if I quote a couple of your articles as long as I provide credit

and sources back to your blog? My website is in the

exact same niche as yours and my users would truly benefit from a lot

of the information you provide here. Please let me know if this alright with you.

Appreciate it!

I have Lateral knee pain? if I squat with weight focused on the outside of foot, no knee pain. I Olympic lift primarily, if this is working should I keep the same cue for the catch portion?

You wrote an entire blog using the wrong term. You are describing a varus not valgus.

Howard, not true. See here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Valgus_deformity

Also see all the research in this area – the term is valgus, or medial knee displacement.

Really very nice that is the highest level of information

Really thank you so much

Hi Brett,

I have been using Kelly’s approach when squatting with feet forward but legs flared out as well.

what i have noticed and would love your opinion on it, is that the VMO started to get really tight and painful causing patellar tracking disfunction.

Would this conclusion be correct ?

Thank you

Hi Bret,

I just bumped into your blog and i am very impressed by your knowledge about knee osteoarthritis knee rehab, valrus, vagus and above all your enthusiasm and passion in this field

I live in rural India and my mother is a knee osteoarthritic patient , around 65 years , and she find it quite painful to do her household chores, walk and wake up comfortably.

Not sure if we have such passionate people in the field of physiotherapy/knee rehab in India.

I would be extremely obliged if you could share certain guidelines that could be of help to us.

Do feel free to reach out to me for any queries that you may have.

Regards

Bilal

Hi Bret

I have been training over a year, and i struggle to activate many muscle groups. Including glutes. Your articles have helped me a lot. I still struggle with chin up/pull ups.. in activating my lats , however after reading your article i think i may be relaxing at the bottom of the movement and i also needs to improve my strength as i can currently only complete one chin up rep, however as i cannot see i am not sure if my form is good. I am working on them by doing eccentrics.

Also i struggle to feel my quads in quad exercises, but i feel them working in strange non quad exercises such as decline ab crunches on a decline ab bench. Any tips here?

Also i struggle to activate my hamstrings in a romanian deadlift, i think i may need to strengthen my core and glutes to protect my lower back as I experience lower back niggles when doing these. I have found that using weight plates under my feet has helped me activate my hamstrings.

Until recently i had never felt my shoulders when doing shoulder exercises and the same with triceps.. until my boyfriend corrected my form.

Training has been very difficult for me indeed as I have battled with feeling resistance exercises working. Although I do always feel bodyweight exercises.

It’s wonderful that you are getting ideas from this article as well

as from our argument made at this time.

Hi Bret! Your videos aren’t showing up for some reason. Could you link to the ones about ankle dorsiflexion?

Hello Bret, your knee Valgus article is extremely detailed and spot on (in my opinion). This is the second time in the last year or so I’ve referred to it. Your work is appreciated – thank you so much.

-Gwenn

what if someone has external tibial torsion and foot pronation seconder to it?

Hi Bret. Your article is super useful. I am a recreational runner and got severe patellofemoral pain as a result of valgus knees and ITB (now much better after 4 months). I’ve been through physio, had an MRI and do Pilates, and your article has brought everything together. I have a lot to work on still and wonder if you have any advice on lateral harmstrings as mine get quite sore towards the end of the day. Thanks. Jazmin

Hi Bret, thanks for the thorough explanation. I have just started to get what has been behind years of pain and how to fix it. I have a valgus knee on the right and really excessive overpronation of my right ankle. I started working with a trainer to increase glute strength and help me with my gait. I strained my gluteus medius a couple of weeks in while running and went to physical therapy. He also wanted to work on foam rolling my IT bands and strengthening my glute meds. So I did, and now my knee is acting up. This is on my good side by the way. Anyway I’m frustrated but determined to keep at it but what am I doing wrong? My IT bands feel tight no matter how much I foam roll it. Also I have hyper mobility syndrome. And very tight calves but great mobility in my ankles if that makes sense. Will the exercises here help with my problem or is my tight IT band not related? Do you have a recommendation for loosening the IT band or so that the strengthening won’t injure me?

Hi Bret,

Thank you so much for this, I find all your articles extremely helpful. I have the “Valgus twitch” issue and it happens whenever I come out of the bottom during heavy squats (anything over 80%), it is causing some patella tracking issues (my knee clicks when I walk or straighten/bend). Do you think a big deload + a lot of corrective exercises would be the best? If so, what exercises would you recommend most for my issue?

Nick

when your femur is 10cm longer than torso, there is no way to squat without leaning forward…

This article is amazing! TY!!

You’re awesome! I love studying for my kinesiology exercise prescription exam and reading everything simplified here or watching your videos on instagram! Everything is backed by scientific research. Thank you bret!

Hey thanks Bret for a great article! Very informative with how to identify where the problem is coming from. Loved how you provided exercises and tips to help correct this. Frequently we have patients walk in the office with instability and knee valgus when performing a squat.

I have had knee valgus as long as I can remember. It’s only recently, in the last 8 months, that I’ve been having problems. My left knee popped out of place twice in one month playing sports. The pain was pretty bad but went away after a few days. It popped out again trying to pivot my foot to do a hip throw. I went to the doctor the first two times, but they found no damage to my ligaments or bone. I’m about to go to a hand to hand combat course and am very nervous. I’m going to look into getting a brace, but I was hoping to fix this problem and not just forget about it. I know that my feet naturally pronate and I have to consciously fix that when I walk. I was told by a physical therapist that my IT band was also just really tight, which puts strain on the inside of my knee; however, I have issues with knee valgus regardless. I could really use some help. I’m very nervous about this course and my knees. I’m too young for bum knees.

Hi My knees Buckle and my left knee will not move up

and down. Does any one know if this is the same as above. I have had them Buckle three times and still cannot walk well. Am in wheelchair till my PT says it is safe for me to walk with a walker. Please help me.

thanks so much for all your articles Bret, i find them all very very useful and so bloody well researched its incredible the effort that goes in. Thanks so much its a really good/easy to understand and access adjunct to my studies as a physiotherapist!