By Eirik Garnas

www.OrganicFitness.com

If there’s one thing we’ve learned from the numerous studies investigating the effects of calorie restriction and exercise on weight loss, it’s that people usually creep up towards their original body weight when they start eating to satiety again or ease up on their training regime.

Despite these poor long-term results, the notion that we just have to exercise more and eat less seems so intuitively right and is also so deeply rooted in people’s belief systems that few question its accuracy. Some folks even claim that calories are all that counts and that it really doesn’t matter what you eat as long as you reduce your energy intake.

While a subset of the population manages to stay relatively lean by doing some type of regular exercise and eating purely based on their energy and macronutrient needs, it’s clear that this doesn’t work for everyone. We’re losing the war against obesity, and it seems that the mantra to eat less and exercise more could be doing us more harm than good.

The laws of thermodynamics

There are two laws of thermodynamics that are especially relevant to body weight regulation; the first law basically states that the form of energy may change, but the total is always conserved, and the second law says that the entropy of an isolated system does not decrease.

When discussing body weight regulation it’s essential that we always adhere to these laws of thermodynamics, and recognize that the amount of energy that is contained in the body will increase if energy intake is higher than energy expenditure. This basic fact is well supported in the literature, and studies show that increased food energy supply is more than sufficient to explain the obesity epidemic (1,2). We essentially eat a lot more calories than before, and this steady rise in energy intake has driven the increases in body weight over the past several decades.

So, it’s well established that weight gain results from an imbalance between how much energy we consume and how much we expend. However, this basic fact doesn’t tell us anything about why we actually overeat.

A general belief seems to be that weight gain simply results from inactivity, poor self-control and gluttony, and the first law of thermodynamics is extrapolated to mean that we can just tell people who are overweight and obese to eat less and exercise more to permanently shed the fat. The problem with this analogy is that the human body isn’t a passive vehicle, but rather fights to maintain what it considers to be a balanced state.

If we look beyond the basic concept of calories in vs. calories out and start to dig a little deeper into human physiology and the scientific literature, it quickly becomes clear why deliberately restricting calories and exercising more isn’t an effective strategy for permanent weight loss for many individuals.

You’re fighting your brain’s hard-wired mechanisms for regulating fat storage

Have you ever wondered how some people maintain a relatively constant body weight year round, why an obese person over-consumes food even though he has plenty of stored energy in the form of body fat, or why restricting caloric intake doesn’t result in a linear decrease in fat mass depending on the magnitude of restriction?

The answers to these questions seem to lie in the intricate feedback system between the brain, gut, and fat cells…

The body fat setpoint and homeostatic regulation of body fat

In 1840, a doctor named B. Mohr was one of the first researchers to discover that obese people often have damage in certain areas of the brain. Since these first discoveries, we’ve learned that the hypothalamus in the brain is the primary control center for the system in our body that regulates fat storage on a long-term basis (the energy homeostasis system).

The amount of fat mass we carry is biologically regulated, and the brain tries to keep body fat within a certain range by influencing our appetite, body heat production, metabolic rate, and whether energy is directed towards fat tissue or lean mass. We essentially have a body fat setpoint that the brain homeostatically guards (3,4,5,6).

If we try to alter the amount of body fat we carry by manipulating food intake and physical activity induced energy expenditure, the brain will act to bring fat mass back to the original level by increasing hunger and decreasing energy output. Since these mechanisms can only prevent a certain degree of fat loss, we will naturally start to lose weight when we reduce the amount of calories we consume and/or exercise more. However, as most people who have restricted calories for some time know, we will also be hungry and tired.

As sustained voluntary calorie restriction significantly impacts the quality of life and requires a high level of discipline, most people eventually start to eat to satiety again and usually creep back up towards their original body weight.

A study published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition clearly illustrates the idea behind the body fat setpoint. They gave lean and overweight subjects a diet that contained 50% more calories than they naturally consumed, and as expected, all of the participants gained a significant amount of weight during the six weeks of overfeeding. The brain tried to defend the body fat setpoint by increasing metabolic rate and body heat production, but these compensatory mechanisms can only prevent a certain degree of fat gain. The interesting thing happened when the overfeeding phase was over and subjects were allowed to eat as much as they wanted for the following six weeks. All of the participants lost the majority of the weight they had gained although they didn’t restrict calories (7).

Calorie restricted dietary interventions point to the same thing; while deliberately reducing energy intake and increasing energy expenditure is necessary for someone who’s already lean and wants to lose more weight, it’s not a long-term strategy for those that are overweight and obese. What we have to do is acknowledge that weight loss isn’t just about making a conscious decision to eat less and exercise more.

The thermostat in your house is a good representation of how the homoestatic system works. If it’s cold outside and you open all the windows to your house, the heating system will kick in to try to keep the temperature around the adjusted setpoint (e.g., 72 degrees F). If you keep the windows open, the heating system will always try to get the temperature back up, but it can only compensate for some of the lost energy. However, if we close the windows, the temperature will quickly rise back to the original setpoint.

The same principles apply to homeostatic regulation of body fat. If we expend energy by exercising more or eating less, the brain will decrease metabolic rate, increase hunger, reduce body heat production, etc. in an attempt to fight fat loss. If we chronically restrict calories we will lose weight, but the body will always try to get things back to what it considers to be a balanced state. When we can no longer take the cravings and begin eating to fullness, our body weight creeps back up towards the original setpoint, and we get a feeling of defeat and failure.

The brain is less sensitive to signals from fat cells in people who are overweight and obese

If the energy homeostasis system was always working properly, no one would be obese. Why doesn’t the the brain respond to the elevated fat mass in people who are overweight by decreasing hunger and increasing metabolic rate, heat production, and use of stored fat as energy?

Part of the answer to this question is found in the negative feedback system between fat stores and the brain. Signaling hormones travel between fat cells and the control center in our head and enable the brain to measure and regulate the amount of body fat we carry.

The key hormone involved in this process is Leptin. Leptin is produced by the body’s fat stores which then travels to the brain where it produces a response at the receptors in the hypothalamus. A high leptin signal is supposed to ramp up the use of stored energy and trigger less interest in food, while a low leptin signal should initiate food seeking behaviour and energy conservation (3,5).

Since leptin production correlates with with the size of the fat stores, people who carry plenty of fat mass produce a lot more leptin than someone who is lean. So, why isn’t the brain responding to these high concentrations of circulating leptin by decreasing interest in food and burning more stored energy? Studies have made it clear that overweight and obesity are characterized by decreased leptin sensitivity, which means that the brain doesn’t respond adequately to the signal from leptin (5,8).

Let’s consider an example to illustrate the effects of leptin resistance on weight gain. Let’s say we have a woman who weighs 300 lbs. Although the fat stores of this person produce a substantial amount of leptin, the brain only responds partially to the signal and therefore thinks that the body carries less fat mass than it actually does. If the woman loses even more leptin sensitivity, the brain will trigger hunger and decreased energy expenditure in an attempt to store more fat and boost leptin production further.

So, it could seem that the more leptin resistant we become, the more body fat we have to carry to maintain the same level of leptin signaling in the brain. If we suddenly become very leptin resistant and the brain only receives half the signal from leptin (hypothetical), fat mass will double over time and we will settle in at a new, higher body fat setpoint.

This is not to say that leptin is the only factor involved in the feedback mechanism between fat cells and the brain, far from it. However, leptin signaling seems to be a key component and is also intuitively easy to grasp in the sense that leptin resistance is similar to a malfunctioning “thermostat”. While a lean person’s fat thermostat keeps body weight around a lean setpoint, the thermostat of someone who is obese is constantly elevated.

Leanness is the most natural state of the human body, and a perturbation of the energy homeostasis system results from a gene-environment mismatch

Have you ever considered the fact that humans and animals living in a specific ecological niche are relatively lean almost year round? Wild animals, hunter-gatherer tribes and some non-westernized populations all maintain a fairly low level of body fat, and increases in fat mass only happen when it’s appropriate for survival and reproduction (9,10,11). As I discussed in my last guest post at BretContreras.com, some traditional populations such as the Kitavans remain lean even though they have access to an abundance of food and are only moderately physically active. Studies also show that hunter-gatherers have leptin levels that are many times lower than westerners, indicating a well-functioning feedback system between fat cells and the brain (8,12).

While this doesn’t mean that we have to emulate the lifestyle of our paleolithic ancestors to be healthy, it does suggest that some aspects of our modern environment perturb the body’s mechanisms for regulating fat storage.

The key in figuring out why the body fat setpoint is elevated in overweight and obesity is to study non-industrial populations that are lean and healthy, and then use this information as a framework for deciphering the latest scientific research on homeostatic regulation of body fat. Only by removing the factors that cause the body to want to store more weight can we design an effective weight loss strategy.

So, how do I lower my body fat setpoint and lose weight?

While there’s still a lot we don’t know about the underlying causes of leptin resistance, elevated body mass setpoint and overeating, it’s clear that changes to the setpoint can be both a cause and consequence of weight gain, and that inflammation in the hypothalamus and food reward play an especially important role (3,5,13). That’s all well and good, but what we really need to know is how we can tweak our diet and lifestyle to lower the setpoint, eat less without deliberately restricting calories, and lose weight. Let’s briefly take a look at some of the practical solutions to long-term weight loss.

Avoid highly rewarding food

Numerous obesity researchers now consider food reward to be an essential factor in the modern obesity epidemic (3,4,14,15). The reward center in our brain labels things as good or bad and makes us seek out energy dense food, warmth, sex and other types of behaviours that benefit survival and reproduction in a natural environment.

The problem is that this system isn’t designed to handle Big Mac’s, donuts, cookies, and other western foods. These processed products are engineered to be addictive in the sense that they contain a wide spectrum of rewarding properties such as fat, starch, salt, sugar, and glutamate. And it’s not just the highly processed stuff that is problematic. Even salted nuts and deep-fried, cured bacon contain a fairly rewarding combination of fat and salt and probably shouldn’t make up a large part of your diet if your trying to lose weight.

So, what this basically means is that the energy homeostasis system evolved to deal with simple, whole foods such as meat, fresh fruits and vegetables, and that modern, processed foods alter the brain’s mechanisms for regulating fat storage. Studies suggest that leptin action in the brain is insufficient to inhibit overeating of highly processed food, because these rewarding products engage powerful neural responses that oppose leptin (5).

It’s really a vicious cycle where hyper-rewarding food triggers addictive processes in the brain and overeating. Energy imbalance leads to more fat mass, leptin resistance, and consequently a higher food intake (15).

Bottom line: Highly rewarding, processed food drives weight gain. A diet primarily composed of simple, whole foods should be the key component of any weight loss program.

Take good care of the trillions of microorganisms that live in and on your body

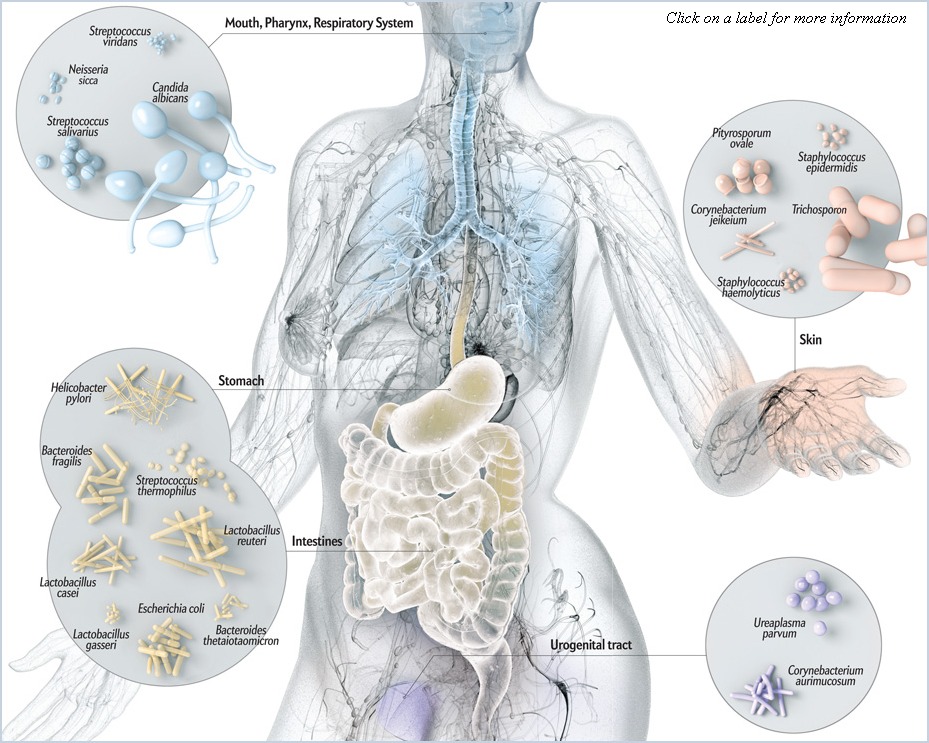

Besides food reward, all of the microbes that live in and on the human body (the human microbiome) seem to play an essential role in the whole process of inflammation, leptin resistance, and weight gain. In a guest post for BretContreras.com, I highlighted the fact that the human body is only 1% human from a genetic perspective and that the microbiome provides functions that stretch far beyond the physiological capabilities of the human host.

The bacteria living in the gastrointestinal tract (gut microbiota) are especially important to our overall health as they maintain healthy gut barrier function, digest otherwise indigestible food components, and regulate our immune system. The problem is that antibiotics, highly processed food, caesarean sections, and other factors associated with life in the modern world perturb the microbiome and promote a state of dysbiosis. The balance of “good” and “bad” microbes in the body has shifted, and the gut microbiota becomes inflammatory.

So, how is it that bacteria potentially can influence systemic inflammation, leptin sensitivity, and weight gain? One of the leading current hypotheses is that dysbiosis increases gut permeability and allows toxins found in the wall of proinflammatory bacteria to interact with our immune system and enter into systemic circulation. These endotoxins then trigger a state of low-grade chronic inflammation and leptin resistance in the hypothalamus (8,16).

The human microbiome is one of the hottest topics in the scientific community at the moment, and numerous studies show that obesity is associated with changes to the gut microbiota (17,18). So, although the human microbiome is shaped throughout our life, it’s largely inherited from our family, and part of the hereditary component of obesity therefore results from transferring an “obese microbiota” from mother to child.

While more long-term human studies are needed before we know to which extent bacteria affect weight regulation, it’s already clear that the human microbiome has a profound impact on our health and well-being.

Bottom line: The human microbiome is involved in body fat regulation. Avoid antibiotics if possible, breastfeed your children, and preferably perform a vaginal birth. Avoid food that promotes the growth of harmful bacteria (e.g., highly processed food, refined flours, sugar), eat food that encourages the growth of beneficial bacteria (e.g., onions, leeks, properly prepared legumes), and eat “probiotics” (e.g., sauerkraut, kefir, dirty vegetables from the garden).

Exercise to improve metabolic health and build muscle

I know I’ve just made the case that exercising really isn’t effective for weight loss, but let’s look a little deeper. About a year ago I reviewed the scientific literature on exercise and weight regulation and concluded that isolated anaerobic or aerobic exercise usually isn’t very effective for weight loss. Most people compensate for the increased energy expenditure by eating more and/or being less active during the rest of the day, and exercising to “burn the fat” therefore makes little sense. This is also consistent with the body fat setpoint theory which suggests that the brain homeostatically guards a certain amount of fat mass.

However, some people respond to exercise by losing a fair amount of weight, and this probably has to do with the beneficial effects exercise has on metabolic health. A moderate amount of exercise has been shown to reduce inflammation and improve leptin and insulin sensitivity (19,20,21,22,23).

For the record, no one’s arguing that heavy resistance training and aerobic exercise aren’t an important part of a healthy lifestyle, it’s just that exercising to lose weight (and keep it off) isn’t effective for the vast majoity of people.

Bottom line: Exercising to “burn calories” makes little sense since most people compensate for the increased energy output by eating more food and/or being less active during the rest of the day. However, regular exercise allows you to eat more food without gaining weight and can also have a small impact on weight loss.

Make sure you’re eating enough protein

The Protein-Leverage Hypothesis suggests that humans aim for a targeted protein intake and that protein is prioritized over fat, carbohydrate, and total energy intake (24,25,26). A recent study also shows that body-weight loss and weight-maintenance on a low-carbohydrate diet seems to depend more on the protein consumption than the carbohydrate intake (27).

One common mistake among people who want to lose weight is to only eat foods such as fruits and vegetables in an attempt to reduce energy intake. While fruits and vegetables are great, they are also very low in protein and energy and should be matched with grass-fed meats, seafood, eggs or dairy to make for a more satiating meal. Eating carrots, cucumbers and tomatoes for breakfast and lunch won’t help your weight loss efforts since your body will crave for more energy and protein later in the day.

Bottom line: Protein is a very satiating macronutrient and should make up at least 15% of your daily energy intake.

Properly prepare whole grains, legumes and other plant foods that are difficult to digest

While everyone agrees that refined flours shouldn’t make up a large part of a healthy diet, some researchers have also speculated that the human leptin system isn’t adapted to a diet based on whole grains because antinutrients and proteins in cereal grains potentially contribute to leaky gut, inflammation, and leptin resistance (8,28,29). While some reports suggest that a grain-free diet is superior to a grain-based diet in terms of weight loss (8), few long-term human studies have found a causal link between consumption of grain fiber and weight gain.

Sensitivity to “toxins” found in grains seems to vary from person to person depending on human genetics, gut health, and whether we have the necessary microbial genes in the intestine to degrade harmful antinutrients and proteins. The problem seems to be that many people make cereal grains the staple of their diet and therefore eat less of more satiating foods such as fruits and vegetables (30).

The fact is that modern wheat is very different from the grains our ancestors used to eat. While celiac disease affects below 1% of the population, some studies suggest that gluten sensitivity is on the rise, and gluten and wheat germ agglutinin can be damaging even for those without celiac disease (31,32,33). A recent study also found that a gluten-free diet reduces adiposity, inflammation, and insulin resistance (34). Although several recent diet books make the case that gluten should be avoided by everyone, the fact is that few long-term human trials have investigated the effects of gluten on body weight regulation and health.

Healthy grain-based cultures usually soaked, grinded and/or fermented grains and legumes to make them more nutritious and easier to digest. Using these traditional processing techniques could be a viable option if you’re sensitive to antinutrients and/or eat a lot of legumes and cereal grains on a daily basis. Even just soaking oats overnight in water and lemon juice and then cooking over low-moderate heat will make for a healthier dish than just plain oats and milk.

Bottom line: Improperly prepared cereal grains are hard on the digestive system, but more research is needed to establish the exact role antinutrients and proteins such as gluten play in the modern obesity epidemic. Eating grains at the majority of your meals probably isn’t a good idea if you’re trying to lose weight, because grains contain some potential gut-irritating compounds and are typically lower in micronutrients and less satiating compared to fruits and vegetables. Traditional processing techniques make whole grains and legumes easier to digest.

Other strategies to lower inflammation and/or unconsciously reduce food intake

Several other factors such as insufficient sleep (35,36,37), high omega-6/omega-3 ratio (38,39,40), low vitamin D levels (41,42) and high cooking temperature (43,44,45) have also been associated with increased low-grade inflammation and/or obesity. While probably not as important as the major factors above, these things also play a role.

Putting it all together

Areas in the brain maintain the size of the fat stores within a certain range by influencing food intake and energy expenditure. In a “natural” environment, the energy homeostasis system regulates body weight at a level that is optimal for survival and reproduction, and leanness is therefore the natural state of Homo sapiens. Dysregulation of the energy homeostasis system and elevation of the body fat setpoint result from a gene-environment mismatch in the sense that the body’s mechanisms for regulating fat storage aren’t designed to handle highly rewarding food, broad-spectrum antibiotics, insufficient sleep on a long-term basis, and other factors associated with life in the modern world. If we try to lose weight by increasing exercise induced energy expenditure and/or restricting calories, areas in the brain that are responsible for regulating fat storage will trigger hunger and decreased energy expenditure in an attempt to regain the lost fat mass. To be able to design a plan that will cause permanent weight loss, we have to address the factors that are causing the body to want to store more weight. Only then can we ramp up the use of stored body fat and eat less without deliberately restricting calories.

I want to make it perfectly clear that deliberate calorie restriction is necessary if you are already relatively lean, but still want to lose more weight. The reason for this seems to be that very low fat mass is below what is considered optimal for survival and reproduction, and the brain therefore protects fat stores by increasing hunger and decreasing body heat production and metabolic rate. I also want to emphasise that although everyone can lose a substantial amount of weight if they adhere to the principles outlined in this post, genetics do matter.

Eat a diet primarily composed of simple, whole foods such as meat, seafood, eggs, vegetables, grass-fed dairy, fruits, nuts, and properly prepared whole grains and legumes. Make sure you get enough protein. Take care of the microbiome by eating prebiotics, beneficial bacteria, and avoiding food that encourages growth of harmful bacteria. Exercise to improve metabolic health, try to get enough sleep, make sure you’re getting enough vitamin D and omega-3, and reduce the production of advanced glycation end products by gently cooking your food.

Individual differences are important, and while some people are able to stay lean while still eating a fair amount of highly-processed food, others must make a significant effort to reduce the reward value of the diet, improve gut health, and follow all the other recommendations.

About the author

Name: Eirik Garnas

Name: Eirik Garnas

Website: www.OrganicFitness.com

Besides studying for a degree in Public Nutrition, I’ve spent the last couple of years coaching people on their way to a healthier body and better physique. I’m educated as a personal trainer from the Norwegian School of Sport Sciences and also have additional courses in sales/coaching, kettlebells, body analysis, and functional rehabilitation. Subscribe to my website if you want to read more of my articles on fitness, nutrition, and health.

Great article! I’m fairly obsessed (in a good way 🙂 ) with my gut health….it’s amazing how it’s tied to so many things! (weight, serotonin levels)

Thanks for another post full of fantastic, and motivating, information 🙂

Amazing article.. very well written !!

Have signed the newsletter for organic fitness, deffinitly some very good articles in there..

Keep it up !!

The problem is people THINK they are eating less but they actually are not. I think calorie restriction still matters for weight management. And since we’re talking about gut health it is way easier to digest less food. Probably they biggest breakthrough I’ve had is that we’ve been taught to eat too much food to grow, when really you need less than most people think.

Incorrect use of “your”once, but an awesome article!!

So, eat less and exercise doesn’t work?

Instead, you recommend that people eat foods that will guarantee that EAT LESS and add exercise.

Yeah, that makes perfect fucking sense.

Lyle

Hi Lyle!

Agree the title can be a bit misleading, but I’m sure you get the picture. Offcourse you have to reduce your energy intake to lose weight (which I state in the article several time)., The problem is that recommending people to simply eat less and exercise more is rarely effective.

I think some previous comments are missing the point.

Point 1. figure out the right number of calories to lose/maintain your weight.

Point 2. longer-term, eating the right number of calories as per #1 will be a lot easier if you eat certain types of foods. If you eat other types of food (sugary, processed, etc.), your hunger is much more likely to get the best of you and you’ll blow through your calorie target.

Great article

Thanks as always

Thanks for summarizing Stephen Guyenet’s blog!

Pretty much exactly what I was thinking, yeah.

Stephan Guyenet is amazing, would recommend everyone to check out his work. Haven’t read that much on his blog, but his review on food regulation is great. Like how he focuses on the disconnect from the ‘ecological’ niche.

However, there are hundreds of research papers on the homeostasis system, leptin and food reward out there. It’s a set of ideas that A LOT of obesity researchers focus on.

Eirik explained better than Guyenet. If there’s any resemblance, I’m pretty sure it’s just a coincidence and inevitable when we’re discussing the same topic.

Good work Eirik, can’t wait to see your next article.

Jansen

The ideas about the fat mass setpoint have actually been around for quite some time, but seem to have gained traction during the last couple of years. Here’s a paper from 1978 discussing the body fat setpoint : http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0091677377907738

In general, it seems that the food reward is a leading topic in obesity research at the moment. However, I tend to focus more on bacteria as I believe they could be as important.

Hey Bret,

Is there anyway to condense all of your amazing articles/posts from you and guests into a file where we could download them into a pdf? I would love to compile your work into a hard copy of the sorts! Thanks!

Lauren

Great Article. I think amount of quality sleep can be added in for weight management as well.

Agree Robin! I added a small note about sleep, but it’s definitely important.

“While fruits and vegetables are great, they are also very LOW in protein and energy and should be matched with grass-fed meats, seafood, eggs or dairy to make for a more satiating meal.”

All plants contain COMPLETE proteins, so you could argue that plant protein is far superior to meat.

Carl Lewis ran his best times on a vegan diet: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aVwe-rgDxEg

Why?. Greater elastic potential.

As with many of the World’s top jumpers.

All plants do not contain “complete proteins.” If you eat a variety of plants you may reach a complete protein source, but by choosing any one or few you may not. What are you referring to?

This article is reasonable as far as the content is concerned but the headline is seriously misleading because the whole article advocates eating less and exercising more…

@JXD Carl Lewis is a known PED user, so you should have written that PED-high diets are superior 🙂

“This article is reasonable as far as the content is concerned but the headline is seriously misleading”.

Head to Youtube & search: The protein myth.

Dairy products again can cause arthritic pain and stiffness in the joints, ultimately affecting joint ROM in athletes/sportsman.

The diet may favor towards increases in physical strength but how the author is relating this article to ‘good health’ in the truest sense, I have no idea. It’s not all about physical strength, you need to get the organs strong first.

Organs do not get “strong”. They function maximally. Or they don’t. Again, what are you talking about??

Sandy, Diet alone CAN either weaken/strengthen the organs. You need to do some research on how caffeine, alcohol, sugar, meat, dairy etc negatively affects/weakens the optimal function of organs.

jdx,

your points are nonsense as im sure anyone with with an education in the field will testify.Diet has zero effect on the stretch shortening cycle.Only soya is a complete plant protein,the rest are incomplete in amino acid profile.Its basic nutrition science,first year of college stuff.You dont seriously reference youtube videos for evidence do you.Many are blatantly biased and not written by credible researchers.

Thanks, Eirik, for two great articles here on Bret’s site. From recent personal experience, I find that boosting my protein intake while weight training has improved my body composition and fitness. However, I am wondering about how much protein is reasonable. I have been following the recommendation of Brad Schoenfeld and others to consume 1 gram of protein per lb of body weight. You recommend at least 15 percent of your total calories to be from protein. This seems to work at lower levels of caloric intake, but if you need 3,000 calories to maintain weight, that’s 450 grams of protein per day! How much is too much?

Hey Marc!

Your numbers are off. 15% protein on a diet of 3000 kcal is 112,5 grams. I’ve simply stated that studies on the protein-leverage hypothesis suggest that going lower than 15% can lead to a higher total energy intake. I tend to recommend more than 15% for most people – atleast if you strength train.

Eirik,

OK–I didn’t divide by 4 calories per gram of protein. Makes sense now. Thank you! Keep the articles coming.

Hey Bret, can you delete my math error????:)

Great article, but food as a reward is ingrained…well it starts at an early age with an mand m for using the potty;) I completely agree with you in theory but people have emotional ties to food that go way beyond eating bad because it tastes so good. If we all saw food as fuel, all the time, we would not have an obesity epidemic… I am an avid Lyle supporter and planned cheats/ refeed help psychologically.. So for the obese perhaps we should focus on giving them tools to see food as fuel most of the time(80/20)… It’s this all or nothing approach that seems to have really steered America wrong. I appreciate these discussions. Thank you!

Sara, your argument relates to exercise psychology where as this article is based on physiology.

If someone wrote an article on sprint biomechanics and I was to reply that it doesn’t reflect the fact that many people are not drawn to running in a competitive environment then that argument is nonsensical in relation to original premise.

The points that you make are well made and may even be valid, however they are a statement and don’t really add anything, they certainly shouldn’t effect anyones opinion of the validity of the original article.

Why is it that whenever there is well referenced article published on the web Vegan warriors show their faces and start posting argumentative posts with references to Youtube and Wikipedia?

Elastic potential of muscles being effected by animal fats… Do some research and stop spouting nonsense you read or watch on the internet.

Great article Eirik, well written and very useful. Thanks

Great Article. thanks so much for sharing that. There is so much to learn about our health.

“Vegan warriors show their faces and start posting argumentative posts with references to Youtube and Wikipedia?.”

The reason vegan warriors post argumentative posts with references to Youtube and Wikipedia is because Carl Lewis is arguably the Greatest Olympian of all time.

If your willing to put in the reading time you will also realise that many other great Olympians followed the same dietary practices.

“Elastic potential of muscles being effected by animal fats… Do some research and stop spouting nonsense you read or watch on the internet.”

I’m not stating elastic potential of muscles being effected by “animal fats”.

Both muscle and tendon are capable of storing energy in their elastic components, but TENDONS (collagen and elastin), along with the FASCIA (collagen and elastin) are far more efficient than muscle in this respect.

This IMO is the secret of the fastest men and women in any running/jumping sport.

Furthermore, diet influences the production/depletion of (collagen and elastin). Collagen is the main structural protein found in various connective tissues, (tendons/fascia). Tendons, are composed of about 86% collagen.

A strict vegan diet doesn’t affect the production of (collagen and elastin). Consuming meat & dairy negatively affects both tendons & fascia. Longer/thinner tendons/fascia are/is capable of storing/releasing more elastic energy, a better environment for overall efficiency.

The greater the collagen production, the greater your elastic potential will be. Consuming the likes of caffeine & sugar negatively affects the production of collagen.

Stronger organs/glands (vegan) give overall lightness (mentally/physically), freeing up energy spent on digestion, resulting in greater physical output.

The consumption of meat & dairy products gives the overall feeling of heaviness, your less elastic/your overall efficiency will be lessened.

This has been my life BTW, testing/trial & error. The data I have compiled is huge.

The bottom line is, you have to get the diet right first because it’s that which will determine if the first links in the chain (organs/joints/blood/connective tissues/fascia) etc are weak or strong/efficient.

I think that by now it’s clear that JXD is a troll and you can safely ignore his remarks.

However, if you choose to read them, you can use them for the purpose of spotting bad science and numerous fallacies (e.g. anecdotal evidence, sticking with one example of a known PED user to prove a given diet is “the best”; vague remarks such as “many athletes” etc.)

“I think that by now it’s clear that JXD is a troll and you can safely ignore his remarks.”

So arguably the greatest/genetically gifted athlete in history is a troll.

He was incredible before PED’s.

“However, if you choose to read them, you can use them for the purpose of spotting bad science? and numerous fallacies? e.g. anecdotal evidence”?.

Name one? or give me an example Bob?.

Your all very keen on science but steering away from nature.

.

I personally think the weight loss process should be simple and not complicated. Sometimes we need to cut back and eat less. Sometimes we need to change our diet into a better one. Sometimes we need to exercise more and consume less for faster results.

great text I can use this for myself

I wish someone would talk about how exercise isn’t required to lose weight. The macro ratios have to be appropriate and you must eat less than you burn. This is like the argument that you need to do a work to get a six pack when it’s the result of the body fat covering your ab muscles. Why are you still argument these points in 2014?

It’s a pain in the butt to count calories but it’s the only way to ensure you will lose weight. People say they don’t have time to count and do it right the first time but they have time to try it over and over for years on end to lose 10ibs.

I’ve never been a huge fan of set-point theory and gene expression as a final arbiter of weight gain and obesity. A great post on this can be found on Lou Shuler’s blog: http://www.louschuler.com/blog/obesity-the-final-answer/

In which he discusses the environmental factors that effect weight gain, offering the following quote:

“If the set point changes in response to our social class, our marital status, or whether or not we watch TV, then it is not a ‘set’ point”.

Although Occam’s Razor can be reductive in most instances it is completely appropriate here. What is a more useful and actionable theory for explaining and understanding weight gain: one built upon many small details beyond our control (set point, genetics, gut flora, evolutionary reward feedback loops, leptin resistance, etc.), or one built upon two simple, overriding details: In our modern environment we eat TOO MUCH crap and move too little. Parsimony would have us favor the latter explanation. We in the western world may be failing in our collective battle against obesity, but just because we are proving incapable of responding appropriately does not make the diagnosis (we eat too much and move too little) or prescription (move more, eat less) wrong.

I am fascinated by the burgeoning field of study regarding the microbiome and the potential it may unlock regarding our well being, however I feel that in the overall big picture of obesity, this as well as other aspects (anti/nutrient sensitivities, etc.) should be regarded as “fine-tuning” if you will.

There’s a reason why IIFYM works. You need a calorie/energy deficit to lose weight. Why make it any more complicated than that? Eat mostly “healthy” foods with a little “unhealthy” food and don’t go over your calorie allowance and you’ll be fine.

Hi Bret,

I’m commenting here because I don’t know how else to reach you and this post is relevant to my question. I bought your book strong curves for women . But I’m having a really hard time just deciphering the whole caloric intake part. I’m trying to figure out how many calories I should be eating and I’m just so co fused by all of the different methods you suggest and the combination of methods and all the calculations. Can you just lay it out for me simply PLEASE??? I’m begging you. I really need to lose some weight and tighten up my diet. I want to start but the whole caloric intake section just confused me and made me feel frustrated. Thank you.

Rachel,

Bret lays it out very simply in the book….

Bodyweight times 14 will basically give you maintenance calories…

Bodyweight times 12 – 10 will give you weight loss calories. (you pick either 12 or 10, personally i use 10).

I have been following the Strong Curves program and it has been working for me just fine!

Good Luck

Hi Angel,

Thank you for your reply! I know Bret didn’t mean to make it confusing, and I’m sure it wasn’t confusing for everyone, but the way you said it was super simple and made it easy for me so thanks so much! I’m sure you are getting great results by following the book and I can’t wait to start doing the same!

Thanks!

Hi there,

Bret, I am a huge fan of your Strong Curves program. I’m just confused on one aspect: should I be consuming any calories I burn off during exercise? At the moment I am following a diet of about 1400 calories with your calculation suggestions featured in the book.I use a HRM to calculate how many calories I am expending during exercise. I’m not sure if I should be eating just a complete total of 1400 calories, since technically after the 400-500 calories i usually burn, i would be at a net calorie amount that is very low. My goal is to lose fat and gain muscle simultaneously, which I know is very difficult. I’ve changed my macronutrient requirements as well to implement more protein. Any suggestions to clear this up would be greatly appreciated. Thank you!

This is my favorite part: “Bottom line: Exercising to “burn calories” makes little sense since most people compensate for the increased energy output by eating more food and/or being less active during the rest of the day.”

In other news, eating vegetables is bad for your health… if you jump off a building and shoot yourself right after.

It’s not a matter of choice. Your metabolism slows after exercise, and appetite increases; and anyone who claims they can resist it forever through “willpower,” is an outright liar.

“although everyone can lose a substantial amount of weight if they adhere to the principles outlined in this post”

Proof, please? Show us the actual case-studies of long-term weight loss from these methods– including those that fail; until then, they’re unsupported claims.

The point is, we’ve heard all this before, and it DOESN’T WORK.

What an amazing article!!!!thank you!!!!Im sharing this for sure!,,,,,

I am no genius when it comes to weight loss but I need some question answered, I was size 6 and ATE myself to size 10, mind you it didn’t just happen, I on purpose increased my food portion and ate more than required, stuff like French fries and burgers, chocolates and the likes plus i didn’t work out, i took a taxi to places i could walk before and there i became size ten. Now please explain to me, if I put my mind to it and reduce my food portion and work just as before, why shouldn’t I lose the weight? I haven’t seen anybody overweight that works hard labour, I grew up having a balanced diet and working in the fields plus grinding millets and all and I was slim as they came. So please explain to me, with all the lipids and protein and brain being misled that if I should unlearn myself from the unhealthy habits and start eating right and working out why shouldn’t I lose weight?

Above here s the photo of the muscular male kid in gray pants no shirt.. a year or more ago in some website page someone posted that this picture is morphed but it looks real whom is he ?

No idea who he is, but this picture isn’t morphed. There ARE morphs of the picture going around, but this is the original, not any of the edited ones. Most of the morphs are very obvious and very bad.

Hi Eirik,

Thanks for the article and the research. While this article doesn’t cover the psychosocial aspects of weight gain/loss, and I do not expect it to, there is at least one line that I would appreciate if you could consider re-framing:

“Avoid antibiotics if possible, breastfeed your children, and preferably perform a vaginal birth.” This sounds like it’s spoken by someone who has never had children and it’s directness implies that these are elements within the direct control of the person experiencing them. Though optimal for these actions to occur, they are not always possible, or controllable. There is enough stigma around these issues in terms of personal shame (not being able to have the very much wanted and planned for vaginal birth, or not being able to breastfeed) and societal condemnation (you fed your child formula!). Antibiotics are, unfortunately, also sometimes necessary and fall under both the personal shame and societal condemnation categories – especially related to children.

I appreciate your consideration.