Today’s article is a guest post from Derrick Blanton. I hope you enjoy it!

Recently, Bret ran a kick-ass post that showed what really happens when big strong dudes pick up heavy shit off the ground. Several comments echoed an oversimplification that I see quite frequently.

Many seem to believe that the act of protracting the scapulae causes rounding of the thoracic spine. This assumption at its core, is erroneous. Are the two actions often linked by movement habit? Yes. Are the two actions inextricably linked by anatomy? No! A strong T-spine will hold an extension independently of scapular position.

The thoracic spine either concentrically or eccentrically flexes voluntarily, or is overwhelmed by load, and flexes period. The location of the scapulae may coincide with this process, but by itself will not cause flexion if the T-spine extensors are strong enough.

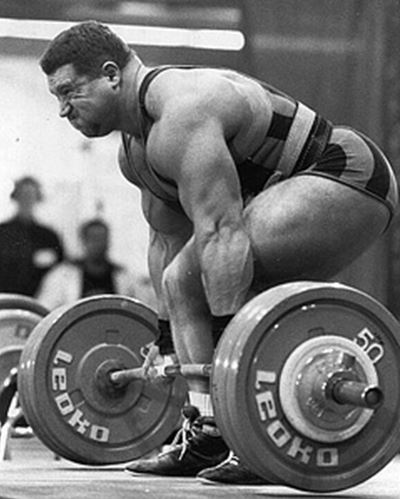

If you are holding your max DL with the spine at a significant angle to the floor, it is likely that both the T-spine is rounding, and the scaps are protracting. But not necessarily. Karwoski here has his scaps protracted big time. But that T-spine looks pretty straight so far!

When you progressively challenge the spine with posteroanterior load, the scapulae eccentrically protracting are the first pair of weak link dominos to fall. The next domino in line is T-Spine eccentric flexion, but this one will likely require further load or time under tension to tank. (And maybe not at all if you are fast off the floor, have freaky long arms, or are just massively strong up the back!)

By the same token, when the T-spine does round, the L-spine will generally hold its extension even further. Most well trained DL’ers flex the L-spine little, if at all, even as the T-spine rounds like a fishing pole.

Realize also that there is a significant difference between passive, eccentrically controlled, or isometrically braced, protraction or flexion. One involves hanging out on passive restraints, including the stretching of muscle, ligaments, fascia and such. The other two add powerful muscular force to the mix, along with the action of the super molecule titin, and this makes for an enormous difference for your soft tissues.

Don’t assume that because a lifter is rounded or protracted that they are just lazily and sloppily hanging on soft tissue. Konstantin looks different rounded over than your grandmother picking up the cat.

Let’s be honest, on max DLs you are hanging on for dear life. Just be aware that past a point of rounding, eccentrically controlled or otherwise, the torque on the lumbar spine and burden on the thoracolumbar fascia will reach a tipping point, and the third energy leak domino, the L-spine, may fall.

This one we would like to avoid.

Postural Confusion

As movement patterns go, thoracic flexion and scapular protraction certainly do often go together, leaning the torso forwards while simultaneously reaching forwards with the arms. And their counterpart movements of thoracic extension and scapular retraction (with depression) often occur together as well.

Yet, these actions do not always occur together, nor do they have to occur together.

I suspect this postural misunderstanding starts early in life. When we were kids admonished to, “Stand up straight!“, our immediate response was to pull the shoulders down and back. This usually coincided with a hard crank of the lumbar spine pulling the ribcage up, and the pelvis into anterior tilt. Presto! We immediately appeared to have a straight upper back. But did we?

Image #1 below is “fake extension”. The giveaway that the lion’s share of the force is not coming from the T-spine extensors is the forward head posture and the elevated rib cage. Incidentally, for all you upper trap demonizers, the UTs are about as deactivated as humanly possible, the “corrective” lower traps are uber-switched on, and the head is still lurching forwards. Strange!

Image #2 demonstrates true T-spine extension. And yes, my hip flexors are tight in both pix. I’m working on it!

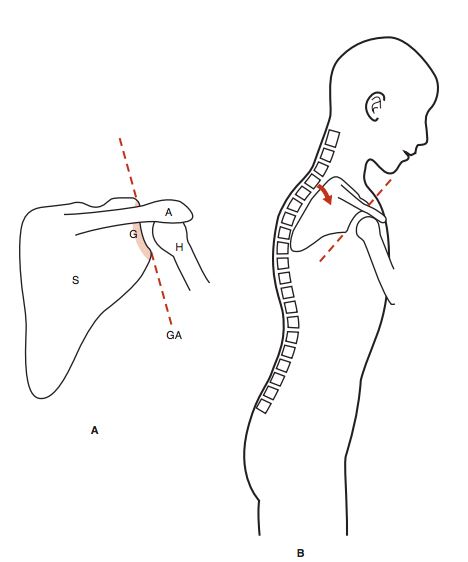

Finally look at the graphic in Image #3. It demonstrates how excessive kyphosis at the T-spine all by itself can position the scapula at a precarious angle for your subacromial space. There is very little the scapular controllers can do to correct this situation. It has to be solved at the T-spine extensor level.

Image #1 illustrates the attempt to solve the Image #3 problem by yanking the scapula down and back. But this strategy is doomed to fail.

Using fake extension strategy #1 is living a lie. And this lie will be exposed when we then ask our scaps to perform their other function: providing stability and dynamic force to move the arms, especially overhead.

On the Other Hand…

This is a tricky topic, and I’m going to muddy the waters a bit here. Is there some truth to the notion that positioning the scaps down and back can erect the T-spine? Yes, I think the scapular controllers can help move the T-spine into extension, albeit in a poorly leveraged, closed chain manner that renders them ineffective at supporting the arms.

This premise would be very difficult to prove or disprove, as to isolate the trap and rhomboid action, you would need to stop the T-extensors from firing at all. Short of a massive Botox injection into the spinal erectors, I’m not sure how you would go about doing this. But it does make sense to me that if the scapula pulls downwards that it will tug on the superior attachment and have a synergistic effect on the T-spine position.

However, in this substitution scenario, while we have now approximated an erect upper back with some clever lumbar and scapular sleight of hand, we now have nowhere to go with the arms. What happens when you go to move the arms forwards or up while still using your lower traps as a postural agent? Awkward!

You will then find out right quick whether the T-extensors are firing strongly enough to support the entire upper back plus any anterior load, independent of scapular positioning.

I submit that it is very useful to uncouple these two muscle groups, and see where you really stand (pardon the pun) with your actual T-spine extension. One way to do this is to hold a light barbell at a 45-degree angle, and explore four different combinations of movement. Note the lumbar spine is in neutral during all the following scenarios:

This last position is the lumbar at risk position, and can actually be a good teaching tool on how to generate stability from the hips. Ah yes, the hips!

Use very light weight, and when you feel the L-spine complaining, screw those hips into the floor, and tighten those abs! Voila! We just shifted the pivot point where it belongs onto the glutes, with abdominal support to buttress.

Perform a picture #4,2,1 sequence, and you are training the T-spine in an upper back good morning type fashion while also training the glutes and abs to stabilize the spine. Challenging, but a great way to enhance your mind-muscle connections, and see where you are weakest.

Overhead Movement and the Scapular Bracing Substitution Pattern

I alluded to it earlier. When you get in the habit of substituting scapular position for true extension of the T-spine, then you are likely compensating for T-spine extensor weakness, which will have nasty ramifications when you try to move a load overhead. Not to mention your general movement posture.

The T-spine extensors need to be the dominant stabilizing force of the upper back. They must literally pull their own weight…plus. When they provide sufficient force, the scapular controllers can better support the arms, and not be wrenched out of alignment trying to prop up the spine!

Here is the optimal scenario for global bracing leading to good, coordinated, scapulohumeral movement:

- Tight glutes.

- Tight abs

- Lumbar in neutral

- T-spine in neutral to extension

- With a stable global base, the lower, mid, and upper traps, plus serratus anterior, dynamically assist and support the humeri.

Here is the not so optimal scenario for lack of global bracing, and an over-reliance on local stability:

- Lazy glutes

- Lazy abs

- Lumbar in hyperlordosis

- T-Spine in kyphosis

- Lower traps locked down to indirectly pull T-spine backwards through superior attachments.

- Lower traps then also take over as last line of stability at the point of action, humeral elevation or flexion.

This has now turned into a group project where the lower traps are forced to do everybody’s assignment, and as a result, the project suffers! Locking the scap down at the inferior angle will severely compromise the actions of the upper trap and serratus anterior. It is now quite difficult to “free the scap up” to glide up and around the T-spine for overhead humeral movement, especially horizontal flexion humeral movement, without losing T-spine extension and caving forwards.

This is because the T-spine extensors are either not strong enough, or are just in a terrible position to fire thanks to lousy stability below. The CNS is now in a pickle. If it lets the lower traps relent and allow the scaps to move, then the lazy ass T-extensors will be exposed, and you are going into a precarious situation, (load overhead), without true stability.

In this scenario, the upper traps do become a problem, as they must switch off, so as not to overcome lower traps, and throw the whole dysfunctional tower out of alignment. But it’s not their fault your core stability is in the toilet!

I believe this is a common mechanism for how incorrect overhead pressing technique can injure people’s shoulders and low backs. A tremendous amount of attention gets placed on the scapula when we discuss overhead lifting. But often the scapular controllers are really just caught in a terrible bind thanks to lousy core stability, particularly lousy thoracic extension. The overhead press, or overhead anything, is an ab, hip, and T-spine extension exercise! And sure, go ahead and hit the delts, tri’s, and traps while you’re at it!

I believe that the scapular controllers are not primarily designed to try and act as T-spine extensors, and prop up the upper back. They assist in postural duties, sure. But they also have other important stuff to do!

When you don’t stabilize globally with your hips and abs, you will find yourself over-stabilizing locally, and lounging on your lumbar spine. Correct this stabilization pattern by doing as follows:

- Build up hip and glute strength, from hip extension, to posterior pelvic tilt, to hip external rotation. By screwing both feet into the ground, and both hips into the socket, massive amounts of pelvic stability are purchased. Plus you will see your excessive anterior pelvic tilt reduced, as the torque acting from below pulls the pelvis downwards.

- Build up powerful anti-extension ab strength. This will keep you honest about where your spinal range of motion is coming from. And lockdown abdominal strength holds the pelvis stable for the glutes to work their magic.

- Build up freaky T-spine extensor strength. This is one of those areas that will respond immediately and gratefully to all types of training, postural and heavy overload. Remember that a lack of ROM in one segment of the spine invariably comes at another segment of the spine.

OK, now you’re good! Sensing stability, your CNS will release the brakes on your traps and rhomboids. They are now freed up to better perform their primary functions as scapular controllers. Your shoulders and low back will thank you.

Excellent article! What are your favorite exercises to strengthen the t-spine extensors?

Thank you, Gina! Bands and chains are very useful in this regard.

First a quick coaching tutorial: When training the T-spine, it is imperative that you pack your neck, and your abs, to make sure that you are focusing on the T-spine, and not the cervical, or lumbar spine. And also to terminate the exercise IMMEDIATELY when form begins to break down in any way. Safety first!

The simplest way to hit the postural path is to throw your toddler up on your shoulders and go for a long walk. 🙂 Otherwise get a couple of chains and wear them. Stop every now and again and do a few SQ’s or lunges, if you like. Just a 5-10 minute walk with 5-20 lbs. hanging off your upper back, and you are going to have a pretty good mind-muscle connection to say the least. You will also quickly begin to understand how the whole spine ties together, as your abs and hips must stay engaged.

For dynamic movement, I like a banded upper back good morning with chest support. Prone on preacher curl, or T-Bar row support apparatus, do upper back flexions and extensions with a band looped around the neck/ upper traps, and affixed to a heavy dumbbell or other stable structure. Can also be done with chains. These are unbelievably effective and feel great.

Since usually we are asking the T-spine to switch on and hold an extension, rather than dynamically roll through its ROM, here are some “brute strength” stability ideas:

1. High bar good morning with isometric pause in bottom position.

2. Front squats, and supra-maximal front SQ holds.

Chain loaded ideas:

3. T-spine RDL.

Load the chain and wrap it around your neck, and grip it in your hands, using your biceps as a safety valve. Hold that upper back extension, as you hip hinge. Again, advanced move with risk of injury if you overload. But effective.

4. Neck loaded Farmer’s Walks. In addition to two heavy ass dumbbells wrap a chain with a heavy ass plate around your neck, and go to town. When fatigued, drop the dumbbells, and use your arms to help you shuck the neck load.

5. Neck loaded Overhead Dumbbell Walks. These are brutal and will destroy your upper traps, shoulder, rotator cuff, and core at the same time. Same deal as above but carry and balance the load overhead.

It is very important to ease into all of these exercises, and progress cautiously. You will soon be craving a force to “push against”. There are more exercises, but this is my special little toolbox. Hope this helps, Gina!

What is the main benefit of protracting the scapula on the deadlift? Does this occur simply because the sheer downward force of the barbell ‘drags’ the muscle down and forward (and it is either not possible or not in the lifter’s interests to exert energy trying to keep the scapula retracted), or is this a conscious decision on the part of these lifters because the leverage is more favourable when the scapula is protracted? I tend to retract my scapula because I like the dense, packed in feeling of my scaps, abs, hips, glutes, etc. becoming one tight little ball of core tension, however I have experimented with protracting the scapula and I can feel how this variation need not affect lower back safety and stability. Is it worth mastering this – does it mean we can lift heavier weights in the long run?

Hello, Konrad. This is a whole other guest blog! (Fortunately, I have no problem rambling uncontrollably, ha ha! 🙂

The benefit of protracting the scaps (and allowing thoracic flexion) is that it approximates longer arms. Longer arms = better leverage at the hip in a DL, and less ROM. This is why you can rack pull a lot more than you can DL off a box, for example. I suppose you could compare it to arching on a bench press to shave ROM.

The benefit of retracting is that in theory, it keeps the bar closer to the body. But really this is a lat function, more than a lower trap, rhomboid function, some synergistic overlap. But your lats can hang with your hips power-wise. Rhomboids, not so much!

So if you can dissociate your lats from your traps, and keep the bar close to the body while unwinding the scaps, then yes, you probably will be able DL more weight. 3-4″ longer arms will make a huge difference in your pull off the floor.

Both approaches are valid in my view. Whether to consciously protract, or attempt to retract is a highly individualized preference, and depends on your goals, your DL style, and your relative limb lengths as well. If your goal is to just absolutely lift as much weight off the ground, then you will almost certainly lift more with protracted scaps.

I cue a “sticky scapula” (thanks, Brett Jones!), i.e., a retraction at setup with the understanding that the scaps are going to unwind as the load gets to a certain point. (Bamboo analogy.)

If you have very long arms, then you may very well be able to keep your shoulders packed and complete the lift. This b/c of a more vertical torso, which cuts direct gravitational pull on the scaps pulling them apart.

Hope that helps!

Wonderfully helpful, thanks!

Bonus footage!

Here is a one minute video. This is a banded technique that will illustrate how lockdown spinal bracing and T-spine extension will free up your scaps to be humeral controllers:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iFIrXnVS6KM

Great post as usual, Derrick.

I’d like to hear your thought on ideal benching form, since the traps, rhomboids, and serratus anterior, as well as shoulder flexion and horiontal flexion are involved here too…

Hey Sven! Ah yes, the bench press. Yeah the scapular controllers are involved, but they’re also now in another bad situation! This is a case where two wrongs make a right.

Btw, it’s a great question which shows that you understand the concept, and are moving on to application.

Benching has some similarities, but some obvious, glaring differences. Standing postural bracing techniques to allow the scaps to dynamically support the arms don’t translate that well when you can’t move the scaps freely to begin with!

(Please read that sentence over and over, and it will start to make sense. I think…)

Also, “ideal” is a very tricky concept, depends on what type of bench you are doing. A PL bench, esp. suited, is fundamentally different than the traditional muscle building bench press…What’s “ideal” changes too, yes?

That said, let’s boil down the overriding concept: the more properly aligned that you can arrange your upper back and scapulae, the more comfortable the CNS feels about unleashing the hounds to move the arms.

(“Properly aligned” sounds like a garbage term, here is specifically what I mean: when the limb that you are moving is supported and stable, and can achieve the ROM in a line of force, with no abrasive impingement, or excessive soft tissue stress. Trust me, your CNS knows when it’s heading into danger and will shut down the agonists. Try to force through this at your peril!)

Obviously scapulothoracic movement and bracing patterns change when you are laying supine, with compression against a bench providing a large measure of spinal and scapular stability. I seriously love to bench, but the scapular controllers being compressed into the bench drives me bat shit crazy. It’s too much stability!

So as a concession to this situation: see my “bad, fake extension posture” from the article? That’s pretty much my bench setup, lol!

I do pop the chest out with a hard retraction of the scapulae, and I do put the brakes on protraction at the top. I also arch a bit too much, although I’m trying to kill that habit. All this is a movement pattern workaround in response to the fact that the scaps can’t move freely. If they get caught “out” (protracted), and can’t get retracted with a heavily loaded humerus bearing down…it doesn’t end well.

To be clear, I don’t think this is necessarily the best movement pattern, and certainly not a great living posture, but it’s probably the best specific approach for this very effective exercise that unfortunately immobilizes the scapulae.

(Quick confession to keep it real here: My bench is pretty narrow. I have discovered that I can protract my scaps a bit, and still get them tucked back into retraction before the humeral head extends. Don’t try this at home! I didn’t suggest this technique…Liability alert, liability alert…ha ha..)

Sven, did I answer the question? Wait, what was the question again? Ha ha! Must go eat…can’t think.

Oh, and one other thought: It’s still a great idea to provide a total body stability just the same, bench or overhead.

Still get tight as can be through the hips, abs, etc. This can be cued as “push yourself through the bench”, or “push your feet through the floor” on the overhead stuff.

Or get “harder than the bar”. (insert juvenile joke here…)

Hey “EnigmaticPuma”, what’s your take on Starrett’s Supple Leopard? See some similar concepts in your post as in his book.

Hey John, big Kelly Starrett fan. Huge. I haven’t read the Supple Leopard book, it looks awesome, but out of his 400+ videos, I have probably watched 300-of them, many of them repeatedly, as KS gets going a little fast sometimes. Not to mention several more that I have been able to dig up through various sources. I found one where he was addressing Google, and thoughtfully going through his thought processes that was particularly illuminating.

He is a savant, and I think along with Bret and Mike Robertson are changing the narrative on spinal bracing. You have to understand when I was coming up, all the cues were just arch, arch, arch until you can’t arch anymore, and then arch again. And it got a lot of people, including myself, hurt.

I also gave KS a shout out in this guest blog that I wrote a while back, which mines some of the same pelvic stability turf as well.

http://bretcontreras.com/enough-with-the-coaching-cues-but-here-are-some-of-my-favorites/

I don’t know where KS stands on the scapular stability/scapular mobility continuum, this is the true overriding concept of this article: The scapula is overused as a postural agent, and this causes fallout when we load the humeri.

Thus, if you are able to configure the hips, pelvis, lumbar spine, and T-spine into favorable alignment, that the scapulae becomes almost a pure dynamic humeral movement synergist, and once you feel this, you will never go back!

Anyway, KS is without question, one of the best and the brightest minds in the strength training/movement field.

Btw, “Enigmatic Puma” was originally intended to be a comedy and sketch channel, but then I got sidetracked making training vids! If I could figure out how to change the name of the strength training stuff to a new channel name, and go back to EP as a creative venue, then I would!

The internet is hard! 🙂

Sorry, “Jon”. (After seeing my name misspelled my whole life, it matters dammit!)