Neural Flossing for the Strength and Conditioning Professional

By Dr. Chris Leib

www.MovementProfessional.com

Neural flossing is physical therapy technique that uses specific exercises to improve mobility to different tracts of the nervous system. Recently, neural flossing has come into vogue in the strength and conditioning community1-4. The utility of such techniques in this sector, however, are questionable at best.

Examples of the lack of understanding and misapplication of neural flossing are far too easy to come by in the popular fitness media:

- A post on Livestrong.com1 described flossing of the sciatic nerve as a “massage” for the nerve when it becomes compressed by muscles and/or bones.

- The Wilmington Performance Lab site2 confidently claimed – without scientific reference – that scar tissue adhesions around the sciatic nerve are the most common cause of sciatic nerve-like symptoms. It went on to add, also without reference, that “fortunately, this compression and poor tissue quality surrounding the nerve can be alleviated in most individuals with neural/spinal flossing.”

The true value of neurodynamic techniques actually lies in the ongoing assessment process that focuses on an individual’s unique injury-specific symptoms, not so much in the techniques themselves. The trouble is, this process of assessing symptomatic response falls outside of the scope of practice of many of the strength and conditioning professionals promoting these exercises.

In the absence of pain, neurodynamic techniques can indeed be performed safely in a strength and conditioning environment. However, in a healthy individual, the nervous system is dynamic; it naturally moves in conjunction with muscle and joint action. Therefore, neural mobility is often already incorporated into good functional movement and mobility practices through dynamic warm-up, making specific neurodynamic techniques superfluous.

All this being said, with their recent proliferation into the broader fitness community, neurodynamic techniques have become needlessly mystified. I present the concepts below in an effort to erase misconceptions and allow for improved communication and referral networks between coaches and clinicians. I also demonstrate the proper application of the techniques into a dynamic warm-up in a strength and conditioning setting (video #3 below).

Criteria for Neurodynamic Treatment

The Maitland Australian Physiotherapy Seminars (MAPS) curriculum describes three major criteria when considering whether neurodynamic treatment would be relevant to a patient’s symptoms:

- Does the neurodynamic assessment technique reproduce the comparable sign (the patient’s chief complaint)?

- Is the response to the assessment technique different on the side of complaint versus the uninvolved side?

- Can the symptom be sensitized (i.e. changed by motion from a distant joint)? For example, is upper arm pain made better or worse with motion at the wrist?

In cases where all three specifications are met, the treatment techniques are actually fairly similar to those used for assessment. Variations are simply made to duration, frequency, and loading strategy (i.e. distal to proximal vs. proximal to distal) based on patient response.

It’s in these subtle adjustments that the techniques become so valuable. It’s also here, in the skilled adjustment process, where the scopes of practice between healthcare practitioners and strength and conditioning professionals diverge.

The Seven Major Neurodynamic Techniques

Below, I’ve put together video demonstrations of the seven major actively-performed neurodynamic techniques described by David Butler in his revolutionary text, A Sensitive Nervous System.

The techniques are as follows:

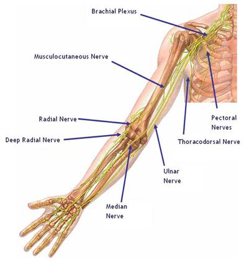

- Upper Limb Tension Test (ULTT) 1 biasing the median nerve

- ULTT 2a biasing the median nerve

- ULTT 2b biasing the radial nerve

- ULTT 3 biasing the ulnar nerve

The median nerve originates in the brachial plexus (network of nerves in the cervical, pectoral and axillary region) and travels down the front of the upper extremity crossing the anterior shoulder, elbow, and wrist (under the carpal tunnel) and ends in the hand.

The radial nerve comes out of the brachial plexus and travels into the posterior arm and then spirals to the anterior arm before spiraling back to the posterior forearm and wrist.

The ulnar nerve comes out of the brachial plexus and travels down the posteriormedial aspect of the arm, forearm and wrist. Compressing this nerve at the elbow creates “funny bone-like” symptoms.

See video #1 here for a demonstration of ULTT’s:

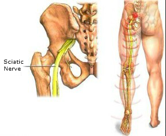

- The straight leg raise (SLR) biasing the sciatic nerve

- Slump test biasing the sciatic nerve

The sciatic nerve is the largest nerve in the human body. It originates from nerve roots L4 through S3 in the sacral plexus and then crosses the posterior aspect of the hip, knee, ankle and foot (branches into tibial and common fibular nerves once crossing the knee).

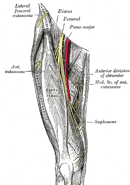

- The prone knee bend biasing the femoral nerve

The femoral nerve, the largest branch coming off of the lumbar plexus, originates from L2-4 and then passes the deep anterior structures of the abdomen (psaos and iliacus) and groin (inguinal ligament) and then travels into the anterior thigh

See video #2 here for a demonstration of lower limb tension tests:

Take note of the use of the word biasing when describing the nerves being assessed. Too often we learn movement assessments and techniques under the guise of isolating structures. In the case of neural motion, it’s both scientifically unproven and anatomically impossible to isolate motion to a specific nerve branch. Moreover, from a practical standpoint, it’s not necessary to isolate any structure in order to assess the need for a neurodynamic approach.

In this complex system of systems, is it really reasonable to think we can isolate a stretch to any one specific nerve?

Neurodynamics in Dynamic Warm-up

The third and final video below is a discussion and demonstration of dynamic mobility exercises that incorporate all of the above-mentioned neural mobility techniques. These movements can be used by both clinician and coach – in the absence of pain – as a dynamic warm-up and as corrective counterbalances for chronic positioning (i.e. sitting, standing, etc.).

See video #3 here:

Remember, the value of specific nerve flossing or neurodynamic techniques lies in the assessment process, which should be reserved for the hands of a licensed health care professional only. As a strength and conditioning professional, it’s wise to find a clinician you trust and can build a referral relationship with. This way, your clients can get out of pain faster, and you can get the most of out of their physical performance.

References

- http://www.livestrong.com/article/287430-sciatic-nerve-flossing-exercise/

- http://wilmingtonperformancelab.com/general/improving-hip-mobility-relieving-sciatic-nerve-pain/

- http://www.tacomastrength.com/news/post/neural-flossing-07252012

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UoUqfOGuEOU

About the Author

Chris Leib of MovementProfessional.com is a licensed Doctor of Physical Therapy and Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist with nearly a decade of experience in treating movement dysfunctions and enhancing human performance. He has written for StrengthCoach.com and FuBarbell.com and has a versatile movement background with a variety of certifications as both a physical therapist and fitness professional. Chris considers physical activity a vital process to being a complete human being and is passionate about helping others maximize their movement potential. Be sure to follow him on Facebook and YouTube.

Special thanks to Travis Pollen of www.fitnesspollenator.com for help turning this piece into something readable and hopefully valuable.

I think this a great article. Neuro glides are gaining a lot of favor even though evidence for them are lacking. As a strength and conditioning coach and 2nd year physical therapy student, we hear about it a lot. weather it is a guest speaker or a professor getting up on his soap box. I would eventually like to see some sort of study that looks at joint ROM and compares it to neuro tension of a given nerve. I would hypothesize that an individual lacking joint rom is also going to be positive for all of the neuro tension test. In addition since the nerves travel through tunnels in certain musculature and bone and we are operating under the assumption that they are getting stuck, it would be fun to look at the combination of soft tissue work, joint rom and neural flossing techniques in combination. sorry for rambling thank you for the article!

*whether

Thanks Jay! I wish I had that same kind of insight when I was in my second year of PT school. You seem like an astute dude. I think a bigger point that you alluded to is that when looking at many, if not all therapeutic interventions, even if a specific structure cannot be validated as being specifically assessed, the techniques themselves can still have positive outcomes on patient symptoms. You will likely spent much of your time in PT school learning how to differentiate structures that are “most responsible” for a patient’s chief complaint. However, the reality is that this practice is often unnecessary. What is more important is that the patient’s movement behaviors are identified and understood. These behaviors include but are not limited to irritability to movement, instability, hypomobility/stiffness, joint derangement (a form of instability), shortened tissue, muscle guarding/spasming, etc. These behaviors are often general but much more effective to understand in the treatment of a patient through non-invasive means. Many of the most well-known PT assessment approaches classify their diagnoses into movement categories independent of a structural diagnosis. For example McKenzie (postural, derangement, dysfunction); Maitland (irritable patient, stiffness dominant, pain dominant); SFMA (mobility vs. stability problem). These approaches work regardless of what structures are involved and are much less concerned about what structures are being treated but instead concerned with whether optimal movement is being restored. In this way, PT and strength and conditioning have a common denominator in that they both should be focused on creating optimal human movement relative to the circumstances.

Great article, should be more of similar. Only one pick up: in clinical neurodynamics reproduction of comparable sign is not required. Only objective tension via neural testing in relation to presence of subjective symptoms or asymmetry/ adverse tension. Inexperienced practitioners get too caught up in trying to find comparable sign in nerve tension testing, it’s a red herring.

David,

When discussing the comparable sign in this context I am re-stating the guidelines from the Maitland Australian Physiotherapy Seminars. This is their criteria for assessment of what to assume to be a peripheral nerve related issue. Basically, these criteria are to differentiate between false positives of nerve tension that are often found. For example many people will have nerve tension symptoms when tested but if it is not the comparable sign then it is not confirmed to be the source of their symptom. That is not to say you cannot treat into the tension to generally improve neural mobility, along with the other structures that are likely restricted in the area. In this case, I don’t think your objection is with inexperienced clinicians but with the Maitland guidelines.

Thanks David,

I’m glad you enjoyed the article.

The mention of the comparable sign was in re-stating the criteria for assessment as per the Maitland Australian Physiotherapy Seminars organization. This is criteria for the assessment of whether a symptom is related to peripheral nerve injury or not. That is not to indicate that neurodynamic treatment cannot be done to decrease general tension of the nerve tissue, but instead is attempting to differentiate from false positives. I think in this case your issue is not with inexperienced practitioners but with the Maitland guidelines.

Whoops! I thought the first comment didn’t go through

Do you recommend Butlers sensitive nervous system book or his earlier mobilizations book?