When I first started coaching the barbell hip thrust in 2006, the main goal was to push the hips as high as possible at the top of each rep. Admittingly, it appeared a bit awkward, as prior to the hip thrust, no coach or trainer ever gave a second thought to “hip hyperextension range of motion.” I recall looking into maximum hip hyperextension range of motion and learned that most people can extend their hips around 10-15 degrees past neutral with bent legs (20 degrees with straight legs).

Through my own EMG experiments, I learned that end-range hip extension maximized gluteus maximus activation, which I later found to be true in numerous published studies. Since then, we’ve found that surface EMG activity isn’t perfectly accurate in terms of measuring motor unit recruitment, but I didn’t know that at the time. So, the goal with the hip thrust was to reach maximum hip extension on each rep, in order to maximize the stimulus to the glutes. To be honest, back then, we didn’t pay too much attention to what the spine or pelvis was doing during hip thrusts. We just pushed sky high and hyperextended everything (spine, pelvis, and hips). Here was the first video posted of the barbell hip thrust off a bench (2009) – notice the super high back position on the bench and the vast amount of hyperextension taking place:

Over time, some individuals started developing low back pain when they were hip thrusting. Interestingly, only a minority of individuals who hyperextended their spines during hip thrusts would begin experiencing issues with their lumbar spines, indicating that some folks can regularly hyperextend their spines under load and not develop pain over time. But the ones who did had to stop hip thrusting, since it consistently caused too much irritation and prevented these individuals from having productive lower body workouts.

At this time, I began pondering ways to make hip thrusts safer for people who tended to hyperextend their spines and anteriorly tilt their pelvises at the top of the hip thrust. In 2010, I had coined the “American hip thrust,” which was characterized by a much lower placement of the bench on the back, and I noticed that it naturally lent itself to less spinal hyperextension and a tendency to posteriorly rotate the pelvis at lockout. However, I didn’t connect this with low back pain prevention and never prescribed it for this purpose.

A couple of years later, I had a client named Molly who just couldn’t have productive hip thrust sessions due to persistent low back pain (she had a strong natural arch and anterior pelvic tilt). I knew that if I could get her to hip thrust pain free, her glutes would certainly grow significantly, as she had great glute genetics.

That’s when I came up with the scoop method. This method prevented lumbar hyperextension from occurring at lockout. I didn’t call it the scoop method at this time, I just called it a hip thrust with PPT (posterior pelvic tilt). Here was the first video ever shown using this method (2012):

After this video was filmed, Molly’s glute growth exploded. She gained 2” on her glutes in two weeks. My Glute Squad accused her of getting implants. She made them all feel her glutes to see that they were real as can be. All she needed was a pain-free way to thrust.

One day in 2015, I was trying to screen capture some of my clients hip thrusting for a featured image on my blog. Every single one of them was tucking their chin and looking forward. It looked strange. I called my friend Ben Bruno and he informed me that he purposely coaches it this way. He told me that he tells his clients to look at the wall in front of them, where the wall meets the ceiling, and keep their gaze there throughout the set. He said that this prevented them from overarching their spines and kept their form solid. As you can see below with Ben’s client Kate Upton, he doesn’t have them exaggerate the posterior pelvic tilt, but the eye gaze doesn’t move upward, and Kate doesn’t move into excessive spinal hyperextension.

This is when I decided to start coaching all my clients with this style of form. To help my clients really understand how to keep their chin tucked, I would hold their head in position as they thrusted so they can focus on rolling their pelvis underneath them as the main mechanism of getting the bar to the top of the rep. In fact, here’s me instructing my friend Hattie Boydle with this method, and it got almost 6 million views! People kept saying that I’m coaching it incorrectly…I was like, I invented the lift, I can coach it however I want lol.

I taught the hip thrust strictly this way for a while. However, one day in 2020, I was teaching hip thrusts to my friend Paul Revelia’s clients at his camp, and some of his girls mentioned to me that they didn’t feel their glutes that much when they posteriorly tilted their pelvises. At this point, I began toying around with a wide-stance hingey hip thrust, and their glutes were on fire. I realized that there’s nothing wrong with the hinge method, as long as you keep it hingey and don’t overarch. I concluded that both the scoop and hinge methods are acceptable styles of technique when performed correctly. Below is the Instagram post I made in 2020 about the two different methods.

Since this time, I’ve been recommending both styles.

My friend Aden (Glute Guru) coined the two styles the “hinge vs. scoop” methods. He made an comprehensive video showcasing the difference between the two methods here:

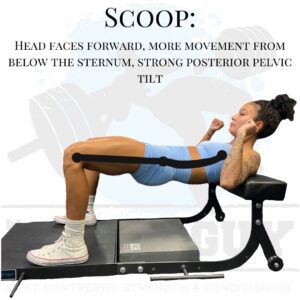

Around 2/3 of people prefer the scoop method: keeping your gaze forward, moving mostly from the sternum down, and posteriorly tilting the pelvis at the top. Here are the main points:

- Low scaps against bench

- Shins vertical at lockout

- Torso forward at bottom

- Move mostly from sternum down, keep a forward eye gaze the entire time

- Posterior pelvic tilt and push with the glutes as high as possible

- “Scoop” the pelvis to lockout

Around 1/3 of people prefer the hinge method: keeping your head, neck, and torso neutral (treating them as one unit), hinging on the bench, pushing your hips tall, and looking forward at the bottom and upward at the top. This variation has you lifting your hips higher at the top of each rep. For my StrongLifting competitions, I use the hinge method because it gets rid of the possible premature pelvic tilt (not being able to reach full lockout but posteriorly tilting without raising the bar to compensate with a pseudo-lockout). Here are the main points:

- Low scaps against bench

- Shins vertical at lockout

- Torso forward at bottom

- Eyes looking at the wall in front of you at the bottom, eyes looking to the ceiling at the top

- Neutral or hyperextended pelvis at the top and push with the glutes as high as possible

- “Hinge” the torso around the bench, keeping the head, neck, and torso in line as one unit

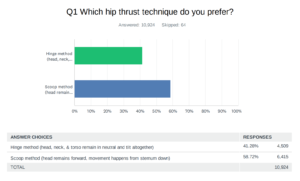

As I stated above, from my experience, around 2/3 of people prefer the scoop method whereas around 1/3 prefer the hinge method. When I sent out a hip thrust survey for my audience to fill out (I got around 11,000 respondents), the results came back confirming my belief. More people still prefer the scoop method.

If someone doesn’t feel hip thrusts in their glutes, have them try these two distinct ways and chances are, they are going to like one or another. Use both styles in your training. Variety is a good thing! Scoop, hinge, pause, 1 ¼, pulse, plus, band, knee-band, smith machine, Glute Drive, BootyBuilder, single leg, b-stance, dual elevated, glute bridge, frog pump…they’re all great!