My friend Rob Panariello asked me to post this excellent guest blog which I’m sure you’ll appreciate!

The Paradox of the Strength and Conditioning Professional

Robert A. Panariello MS, PT, ATC, CSCS Professional Orthopedic and Sports Physical Therapy Professional Athletic Performance Center New York, New York

The role and responsibilities of the Strength and Conditioning (S&C) Professional are very distinctive, especially when considered in comparison to the other organization “team” of professionals whom are also responsible for the medical care and athletic performance of the athlete (i.e. medical and rehabilitation professionals, position/assistant/head coaches, etc.) This article is certainly not to minimize the unique responsibilities and skills of these other various contributing organizational “team” of professionals, but simply to express the distinct differences in the methodology and skills that are necessary for implementation by the S&C professional as part of their responsibility and contribution to ensure the optimal enhancement of various physical qualities and athletic performance success of the athlete. One of the foremost differences of responsibility of the S&C professional when compared to the other “team” professionals, all whom contribute to both the athletes and team success, is the necessary high level of programmed and applied “stress” to the athlete, via the athlete’s athletic performance enhancement training program. It is this appropriately programmed and application of “stress”, that is considered the fabric from which the training program is founded.

The S&C professional is responsible for the enhancement and achievement of the athlete’s (and team’s) athletic (various physical qualities) performance goals. These responsibilities include, but are not limited to, an evaluation process to determine the deficits and “physical needs” of the athlete, the preparation (work capacity) of the athlete for the ensuring prescribed high intensity training, and the development and implementation of a safe and appropriate athletic enhancement training program design. This program design will entail a pre-determined selection of specific exercises to be performed by the athlete, over time (training period), at various prescribed and applied exercise volumes (i.e. repetitions) and intensities (i.e. weight, velocity, etc.) to assist the athlete to achieve their athletic performance goals as determined at the time of the athlete’s evaluation. One very essential component of the prescribed athletic enhancement training program is the incorporation of appropriate levels of predetermined (per individual) levels of stress that must be applied to the athlete. These (often high) levels of applied stress are both crucial and necessary for the “adaptation” of the body to take place. This adaptation is vital for the development of the athlete’s various physical (strength) qualities to transpire in preparation for athletic competition.

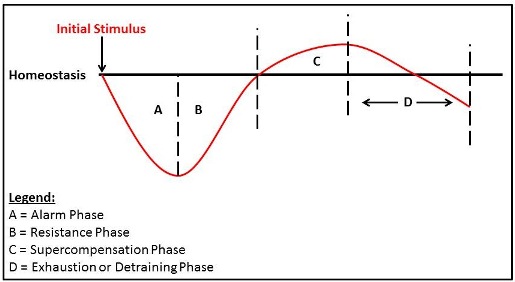

The fundamental model of training, as well as the ensuing adaptation process is derived from the “General Adaptation Syndrome” initially outlined by Hans Selye in 1936 and later refined by Selye in 1956. This fundamental model concept is also known in the literature as the “Supercompensation Cycle”. This stress response model (Figure 1) is initiated by means of an Alarm (Reaction) Phase, as a (training) stimulus (application of stress) results in a disruption of the homeostasis of the body. The body then responds to the applied stimulus (Resistance Phase) by recovering and repairing itself while prompting a return towards the initial (homeostasis) baseline. The Resistance Phase is followed by a period of “Supercompensation”, where the body adapts to the initial (stress application) stimulus by rebounding above the previous (homeostasis) baseline in order to better manage the initially applied disruptive stimulus should it present itself once again. The “Exhaustion” or “Detraining” Phase ensues with a reduction to the body’s initial level, or below the level of homeostasis, as a result of an inappropriate application of a stimulus (i.e. too much, too soon, or inadequate). An in-depth analysis of Selyes’ “General Adaptation Syndrome” is beyond the scope of this dialogue, however it is highly recommended that the S&C professional become familiar with Selyes’ model.

Figure 1. The Stress-Response Model based on Hans Selye’s “General Adaptation Syndrome”

The Paradox of the Strength and Conditioning Professional

The organization’s “team” of various professionals all apply a variety of predetermined physical stress for adaptation to enhance the athlete’s physical condition and athletic ability. Often times the team physician may find it necessary to perform surgery, applying the physical stresses of cutting, drilling, etc. in an attempt to restore the native anatomy of the athlete for the optimal return to athletic performance. The rehabilitation professional also applies physical stress in the form of modalities, manual skills, an array of exercise intensity, etc. for adaptation as the athlete will eventually (a) return to play (in-season) or (b) return to the participation of the off-season athletic performance enhancement training program. The position/assistant/head coach will apply physical stress during practice (i.e. drills) to perfect an athlete’s level of game related skill.

Although some S&C professionals do participate in the athlete’s post-injury/post-surgery rehabilitation, it could be argued that no other organization team professional will apply the high levels of physical stress to the athlete that transpires during the athletic performance enhancement training program.

It is essential that the S&C professional apply (high) stress to the athlete in the form of “intensity”. This high level of applied (physical) intensity is much greater than the physical stress that an individual may be accustomed to when compared to the daily activities of life, the fitness workout at the gym, the physical rehabilitation following injury or surgery, as well as many other scenarios where “intensity” (stress) is applied for the adaptation and enhancement of various physical (strength) qualities. The application of intensity may transpire via various methods such as applied exercise weight (load), exercise velocity, plyometrics (jumps/throws), etc. The setting of this applied high level of stress is monitored by the S&C professional to ensure as safe an environment as possible, one that is surely “safer” and superiorly “controlled”, when compared to the environment that cannot be controlled, the environment of chaos that emerges in the arena of athletic competition. If the athlete were not exposed to the essential (high) stresses that are required to occur during the athletic enhancement training program, how would any organization team professional expect the athlete to (a) optimally enhance their various physical strength qualities and performance for athletic competition, and what may be of greater significance, (b) tolerate the extreme uncontrolled stresses of athletic competition?

Throughout my career I have had many conversations with various S&C professionals whom have stated that during their career they were presented with circumstances where other organization “team” members appeared to have a hesitancy for approval of the application of high stress to the athlete during the athletic enhancement training program, and/or where the S&C professional was actually prohibited to prescribe and apply a program design of high stress to the athlete due to the concern that possible harm may occur to the athlete. I myself also had such an experience that occurred during my ten years as a Head S&C Coach at a Division 1 University. If the athlete is allowed to participate in an S&C professional supervised and organized athletic enhancement program, yet is prohibited from the application of appropriately programmed high exercise stress, are we then placing the athlete at greater risk of injury on the day of athletic competition?

The Incidence of Athletic Injury: Sport Participation vs. Weight Training

One may ask what does the first time; ACL knee reconstructed football player, a pitcher with a surgically repaired rotator cuff and/or labrum, a hockey player that received a concussion, an MMA fighter with a low back injury, and a basketball player with torn ankle ligaments all have in common? Following the occurrence of the injury and/or surgery (if necessary), as well as the accompanying post-injury/post-surgery rehabilitation and testing, these athletes are allowed to return to the high stress environment where their injury initially occurred, the environment of game day. It is well documented that the majority of athletic injuries that transpire during the season of play, take place during the day of athletic competition (Table 1), as well as the incidence of “traditional” sport injuries far exceed the injuries that occur during weight training and weightlifting type participation (Table 2). The lower incidence of “weightlifting type” injury may be due to the establishment of an appropriately programmed high intensity applied in “controlled” environment at the time these heavy (high stress) weights are lifted. If the athlete is permitted to participate on game day, in an arena (environment) of uncontrolled (chaos) high stress, why then would there be hesitation for the application of appropriately programed and applied high stress, in a controlled environment (weightroom), during the athlete’s enhancement performance training?

Injury Rates During Men’s Football Games 35.9

Injury Rates During Men’s Fall Football Practice 3.8

Injury Rates During Men’s Spring Football Practice 9.6

Injury Rates During Women’s Soccer Games 16.4

Injury Rates During Woman’s Soccer Practice 5.2

Injury Rates During Games (15 Sports) 13.8

Injury Rate During Practice (15 Sports) 4.0

*An exposure is defined as 1 athlete participating in 1 practice or game.

Table 1. Injury Rates Per 1000 Athlete Exposures for 15 Collegiate Sports (Modified from Hootman et al)

School Child Soccer 6.20

UK Rugby 1.92

South African Rugby 0.70

UK Basketball 1.03

USA Basketball 0.03

USA Athletics 0.57

UK Athletics 0.26

USA Football 0.10

Weight Training 0.0035

Weightlifting (Clean & Jerk, Snatch) 0.0017

Table 2. The Incidence of Injury Per 100 Participation Hours of Various Sports of Participation (Modified from Hamill)

Thus is the paradox of the S&C professional. The development and integration of an appropriate high stress training program, performed for adaptation in a safe and controlled environment, in an effort to also prevent the occurrence of possible injury during the athlete’s participation in such an athletic enhancement training program.

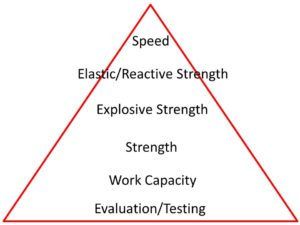

Addressing the Strength and Conditioning Professional’s Paradox

One consideration in addressing the S&C professional’s paradox is based on the philosophy and model of the “Hierarchy of Athletic Development” (Figure 2) by Hall of Fame S&C Coach Al Vermeil. Coach Vermeil’s model (pyramid) of hierarchy for the development of an athlete’s various physical qualities occurs along a specific continuum. This continuum is initiated at the base of the pyramid; with the eventual progression to each ascending (succeeding) physical quality level once the criterions of the present physical quality level of training is achieved. This is certainly not to insinuate that only one physical quality is solely trained at a specific period of time. To the contrary, several physical qualities may be trained during the same “hierarchy” period, however, it is recommended that only a specific physical quality should be the main emphasis at each corresponding physical quality developmental “stage”. What also transpires during the “stage” of each physical quality of development is the application of stress, which is essential to ensure the body’s “adaptation” and continued assent upon this model of physical development. The appropriate level of programmed and applied stress will depend upon many factors such as the training experience of the athlete (i.e. novice vs. advanced), the age of the athlete (i.e. high school vs. professional), the sex of the athlete (i.e. male vs. female), and if the athlete has had a recent injury or surgery to name a few.

What is particularly important is the second stage of this model, the stage of the development of work capacity. An athlete must be prepared for the eventual application of high stress. Increased levels of programmed stress applied to an unprepared athlete will place the athlete at greater risk of injury.

Figure 2. The Hierarchy of Athletic Development (Al Vermeil)

The 100% “Safe Intensity” Exercise Performance

The prescription and application of exercise performance arises in many professions and situations. Some examples include the appropriate levels of programmed physical stress prescribed by the rehabilitation professional, the personal trainer, and the S&C coach to their patient/client/athlete for adaption of the body to take place. As previously noted, for the necessary adaption (physical enhancement) of the body to occur, the homeostasis of the body must be “disrupted”. This disruption of homeostasis via applied stress will cause an increase in adaptation to not only muscle, but to bone, ligaments, tendons, the physiological and cardiovascular systems, as well as other anatomical structures and “systems” of the body. A truly “100% safe intensity” exercise performance will likely allow for too inadequate (insufficient) an applied stress, resulting in no change in disruption of the body’s homeostasis and subsequently no obligation for the body to respond to this insufficient stress stimulus. Therefore, the consequential effect of the application of an inadequate (too low) level of physical quality enhancement training stress is a loss of valuable training time.

All exercise intensities that are applied with proper preparation, prescription and programming, place a higher than “normal/safe” level of stress to the body. This high, yet appropriate level of applied stress is necessary for a disruption of the body’s homeostasis to occur. All programmed high stress exercises have both risk and benefit. It is the responsibility of the S&C professional to incorporate the appropriate levels of programmed stress, to the selected exercises to be performed by the athlete’s for whom they are responsible, in a controlled (safe) environment.

The S&C professional has the unique responsibility of applying high stress to the athlete, likely higher stresses than any other member of the accompanying organization “team” of professionals. The application of high stress is necessary for the athlete’s adaptation and enhancement of physical qualities for the participation in the often violent and uncontrolled arena of sport. Injured athletes are commonly allowed to return to the highest known environment of stress, game day, often the same environment of where their injury took place. The S&C professional is required to not only develop the athlete’s various physical qualities for the enhancement of athletic performance, but perhaps of even greater importance, to prepare the athlete for the uncontrolled, chaotic, and often violent environment of athletic competition. To prohibit or ignore this requirement will not only deprive the athlete of their physical/athletic potential, but likely place the athlete at greater risk of injury as well.

References

- Hamill, B, “Relative Safety of Weightlifting and Weight Training”, Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 8(1): 53 -57, 1994.

- Hootman JM, Dick, R, and Agel J, “Epidemiology of Collegiate Injuries for 15 Sports: Summary and Recommendations for Injury Prevention Initiatives” Journal of Athletic Training, 42(2): 311 – 319, 2007.

- Selye, H. The Stress of Life, New York McGraw-Hill Book Co. Inc., 1956

- Vermeil, Al Personal Conversation

Table 2 is absurd. Squats are twice as dangerous as quick lifts? ‘Athletics’ are 5.7x more dangerous than football? Hell, football’s only 30x more dangerous than lifting? Arrant nonsense.

And if schoolkid soccer is 62x more dangerous than football I’d suggest it’s because we count boo boos differently in the two populations.

Scott,

I certainly respect and understand your thoughts. This particular study was performed in the United Kingdom and was based on both a questionnaire as well as other reported research (literature review). In the United Kingdom there certainly would be a greater volume of “schoolchild soccer” (i.e. 13 – 16 year old children) players than American football players, based on the popularity of that sport (soccer) in that particular country. I am also of the opinion that there is very likely a much greater number of “schoolchild soccer players” when compared to the number of University or Professional soccer players in the U.K.. With a greater volume of participants we would probably see a greater number of injuries. If this same study were performed in the United States perhaps the outcome may have been more in line with your thoughts, (if I am interpreting them correctly) as Hootman’s study demonstrates.

My intention with regard this guest blog, is to simply state the necessity for the application of (often high)stress in training. If participation in competitive sport results in a higher injury rate vs. an appropriately programmed and applied athletic performance enhancement program, performed in a ‘safe” and ‘controlled” environment, and the athlete is permitted to participate in athletic competition, why is there (at times) a hesitation to allow this same athlete to participate in an athletic enhancement training program? Regardless of the order of the various sports “statistical injury numbers”, participation with the utilization of weights fell at the bottom thus providing some “ammunition” to any S&C professional confronted with such a situation as previously described.

Thank you for your post and thoughts.

Scott,

Why is the table “absurd?” A published study most likely collected data on injury rates, participation rates, and passed a peer-reviewed approval process. Be careful of forming your personal opinion without some actual numbers and evidence to reach conclusions.

Personally, anecdotally, I have seen more athletes injured with Squats than with Snatch, Clean, or Clean & Jerk. Consider this: maybe more athletes and coaches are “afraid” of the Olympic lifts because of perceived or assumed injury risk, while more likely to go with “safer” lifts such as a squat. This increases participation in one (squat) while decreasing another (Olympics), and an assumed lower risk might lead to less worry about appropriate coaching, technique, proficiency, and heavier weights (increased injury).

Rob,

“In the United Kingdom there certainly would be a greater volume of “schoolchild soccer” (i.e. 13 – 16 year old children) players than American football players, based on the popularity of that sport (soccer) in that particular country. I am also of the opinion that there is very likely a much greater number of “schoolchild soccer players” when compared to the number of University or Professional soccer players in the U.K.. With a greater volume of participants we would probably see a greater number of injuries.”

Sure, that’s presumably what the ‘per thousand exposures’ was intended to correct.

I’m certainly with you on the paramount importance of heavy barbell training; big heavy deep belted squat fan, myself.

Nice, good and useful article – it offers or suggests few landmarks for the training methodology… it is a perspective. I wouldn’t generalize the “dictatorship” or “the doctrine” of the high stress solicitations… are so many variables! Still loved it – back to the roots, “classic stuff” always sure and of course will work :).

By the way… This medical reports are always subject of polemics. They are often epidemiologists job and usually are working/using medical infos and data (health department informations). They are not establishing ratios between risk probability and the mass of participants, conditions, etc… Also they are rarely establishing a system or factor of equivalence between different types of pathologies. In France are similar studies which says soccer 4,25x more dangerous than rugby. I’ve verified the original sources – they were considering the number of injuries. They were 30.000 /year on the soccer fields vs 7000 in rugby. Well number of participants is 1 million in soccer for 250.000 in rugby. Also in soccer risks and type of injuries are “thousand times” lighter (most of them are ankle sprains or elongations) than in rugby who every year puts a kid (at least one)in wheelchair for the rest of his life.

My numbers are not may be very accurate (+/- 10%), but this do not change the point of my observation. I’m wondering how are they allowed publishing such shit. So…What ever. It was just anecdote about how could possible bring confusion such studies.

In the case of adult players and making exception from accidents – serious impacts, etc. it demonstrates a limited perspective classifying injuries causes by the place/moment where/when they happened. Most of them are latent chronic issues generated by a long practice and they just happens more often during the games because a higher intensity level of the solicitations… Considering youngsters training; I’d definitely replace “work capacity” with a different notion (in Mr. Vermeil’s pyramid)… it sounds so awful…Or someone should define work capacity, because if is it about endurance, than this is totally wrong.