The importance of strength

If you are a strength coach, I’m guessing that you probably spend a lot of time on building programs designed to increase your athletes’ strength. Call it an educated guess.

Or, if you’re a personal trainer, I am guessing that you might want to help your clients gain strength so that they can lift a greater volume of heavier weights and improve their body composition. Again, I might be reaching here, but please stay with me.

And if you’re a physical therapist, you might be putting late-stage rehabilitation programs together that help your patients improve their full function after regaining pain-free range-of-motion. That sounds like increasing strength is a big part of the process.

The bottom line is that almost every professional working in the evidence-based strength and conditioning, fitness, rehabilitation, exercise therapy, and exercise in healthcare professions needs to understand how best to improve strength in their patients, clients or athletes.

Programming for strength gains

So how do you go about developing your own strength training programs? How do you decide whether to use more volume or less? To train to muscular failure or not? To use high or moderate percentages of 1RM? To use short rest periods or long rest periods?

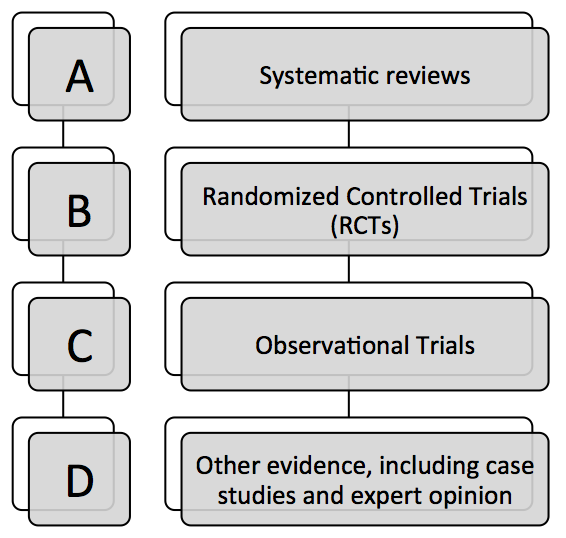

If you’re an evidence-based practitioner, then when you review the evidence before deciding how to structure your strength-training programs, you naturally refer to a flow-chart that looks something like this:

Unfortunately, there haven’t been that many systematic reviews showing how different strength training variables (like volume or percentage of 1RM) affect strength gains. One or two have been performed in relation to volume but that’s about it. That means it’s a lot of hard work to be a truly evidence-based practitioner when it comes to understanding how to alter training variables to best gain strength. You need to wade through all of the randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to see what they say.

As you can see, the level of evidence for observational trials and other evidence is below that of RCTs. That means before you start reading observational trials and seeking expert opinion, you should really read and assess the evidence provided by the RCTs.

Focusing on long-term results

And don’t forget that the level of evidence is higher where it directly measures the variable you want to understand, which in this case is long-term strength gains. So studies exploring the long-term effects of different training variables on muscular strength are more important than those exploring the immediate effects of different resistance-training workouts on muscle protein synthesis, post-exercise hormone responses, or the molecular signaling processes that underpin gains in strength and size.

Remember, we once thought that post-exercise hormones were the key for long-term hypertrophy. So it’s likely that our current models are not perfect. In fact, they are always in a state of flux. Mitchell et al. (2014) recently reminded us of this when they reported that long-term muscular size gains were not correlated with short-term rises in muscle protein synthesis, nor with the phosphorylation of many of the signaling proteins.

In reality, our understanding of these acute study results is constantly changing, which is part of what makes it so exciting to study. Equally, our understanding of the results of long-term trials will never change, which makes their findings more reliable.

For example, if a long-term trial monitored one group who trained bench press with an average load of 200lbs (a high percentage of 1RM), and another group of similar strength levels trained bench press with an average load of 150lbs, (a moderate percentage of 1RM), then the resulting difference in strength gains tells us something about the effects of high or moderate percentages of 1RM that will likely never be superseded.

To paraphrase Henry Rollins, the long-term effects of training with 200lbs will always be the long-term effects of training with 200lbs (for trainees with the same strength levels).

Sorry, I couldn’t resist that.

The important thing is that if you are helping people improve their strength, and you consider yourself to be an evidence-based strength coach, personal trainer, or physical therapist, then you need to know what the long-term trials tell you. Annoyingly, the literature is extensive and it’s hard to track all of the studies down.

Fortunately, Chris has pulled them all together and described the results in a single e-book, called simply “Training for Strength”. Let me tell you how you can get a copy.

How to get your copy of Training for Strength

If you’re currently a paying subscriber to our monthly Strength & Conditioning Research review service, you’re going to receive a free bonus copy later today. We like to look after our subscribers.

If you aren’t a paying subscriber yet, to get your copy of Training for Strength, just sign up to our monthly review service today. Shortly after completing your subscription, you will be emailed a free bonus copy of the Training for Strength e-book (PDF and e-reader versions).

And don’t worry, we are not trying to trap you into a long-term subscription! Signing up to the monthly review service does not commit you to more than one edition, which costs just $10. And you can cancel your subscription whenever you like. So unless you absolutely cannot spare $10 to see whether you like our monthly review service, there is no reason at all to miss out on this e-book.

Click subscribe now and give it a try!