Last week I wrote about one of the pitfalls of progressive overload. In efforts to set continuous personal records, many individuals allow themselves to gain too much weight and accumulate too much fat which leaves them looking soft and flabby. There are more pitfalls to progressive overload, and today I’d like to talk about another one, which I call, “Being in a Rut.” I believe that this is one of the most important concepts in strength & conditioning that nobody seems to talk about.

Merits of Progressive Overload

Before I start I’d like to iterate that progressive overload is one of the most important factors in achieving results. If you’re lifting the same amount of weight for the same amount of reps next year as you are today, chances are your muscles won’t look much different. However, linear progressive overload for advanced lifters does come at a price.

Being in a Rut

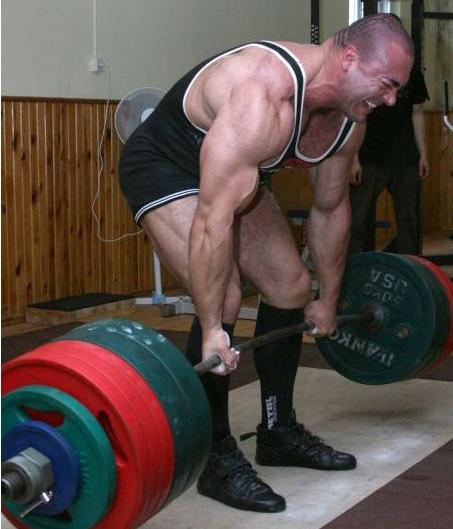

Often, in our continuous quest to achieve PR’s, we push ourselves further and further to the point where our joints or soft-tissue starts aching. Perhaps your shoulder starts acting up when you train your delts or perform the bench press exercise. Maybe your arm bones ache when you curl. Perhaps your back feels dodgy when you deadlift. Or maybe your knees don’t feel up to par when squatting.

Here’s how it usually works:

- You’re making steady progress in a particular lift and you get really excited about the possibility of reaching a milestone (say a 100lb chin, 200lb military press, 300lb bench press, 400lb squat, or 500lb deadlift).

- The closer you get to the milestone, the more your joints or soft-tissue starts aching.

- You ignore it for a while and kid yourself into thinking it will go away.

- It doesn’t go away and things get worse. Now your “acute” problem has become a “chronic” problem.

Sometimes You Can Get Away With it

Sometimes you make a deal with the devil and end up winning. You train through pain and things end up fixing themselves. It’s happened to all of us long-term lifters. We say to ourselves, “My back aches but I have a deadlift session planned and I’m not going to miss it.” Maybe we even push the pedal to the medal and set a PR. Every so often we do this and the next day we somehow feel like a million bucks; our bodies are not sore and our pain has vanished.

Digging Yourself Further Into the Hole

What I just described is the exception, not the rule. A majority of the time when we train through pain we just end up digging ourselves further and further into a hole. All of a sudden, we’re completely in a rut and are forced to make serious training modifications to address the problem. Now every single time you bench your shoulder kills, every time you squat your knees ache, or every time you deadlift your back hurts, and the pain persists throughout the day. Essentially you’re living life in constant joint pain.

Nip it in the Bud Right Away

Your ability to nip these ailments in the bud as quickly as possible is an integral part of your maturity as a lifter and will play a large role in your ability to train consistently over the long-haul.

Think about it. Pain is the brain’s way of alerting you about problems down the chain and is a protective mechanism. Usually if you ignore the signals, there will be consequences.

Painful lifting is rarely a good idea – in the words of Mike Boyle, “if it hurts, don’t do it.”

Improvise!

If your shoulder starts hurting when you bench, stop benching and call it a day. Next training session, find an alternative that doesn’t hurt. Your chest is not going to deflate if you stop benching and switch to push-ups. In fact, some lifters see increased pectoral mass when they switch to push-ups for a few weeks, most likely due to the higher rep ranges. Maybe push-ups still hurt and you can only do neutral grip dumbbell floor press.

Whatever the case may be, avoid any exercises that don’t feel right and try to find one that’s pain-free. Notice I said “one.” One exercise is sufficient for maintaining hypertrophy and strength; you’re trying to provide a maintenance stimulus while sparing the tissue so it can heal.

If you can’t find an exercise that’s pain-free, avoid training that joint altogether. I’ll provide some examples.

If your knees always hurt when you squat, stop squatting and see if you can get away with reverse sled dragging for the quads. If you can’t, then avoid training the quads altogether and stick to posterior chain lifts for a few weeks. Your quads won’t shrivel up if you stick with conventional deadlifts, hip thrusts, back extensions, and glute ham raises (or even leg curls) for a few weeks. First, you’ll give the knees a chance to recuperate. And second, you’ll strengthen the hips which can positively impact mechanics toward a more knee-friendly manner which will help spare the knees over time.

I referenced the shoulders in benching earlier in this section. Let’s say you can’t find an exercise that doesn’t hurt. In this case simply hammer the upper back for a few weeks. This will allow the shoulders to heal while building increased scapular stability which will confer a protective effect on the shoulders over time.

This is why it’s important to have a large toolbox so you’re able to be innovative and figure out joint-friendly but effective exercise variations.

The Stanford Marshmallow Experiment

In 1972 a researcher performed what became known as The Stanford Marshmallow Experiment. Essentially children aged 4-6 yrs old were offered a marshmallow but if they could resist eating the marshmallow for 15 minutes they were promised two instead of one (actually the children chose their favorite treat out of marshmallows, Oreos, or pretzel sticks). Only a third of subjects could resist, and these children ended up being rated more competent by peers and scoring higher on SAT scores when measured around ten years later. Check out the video below…cute kids!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6EjJsPylEOY

How this Relates to Lifting

As a lifter, you can be greedy and play Russian Roulette with your joints. Nobody wants to miss bench press day or a heavy deadlift session especially when they’re on a roll and have been making steady progress. But if you aren’t feeling right and you go ahead and train through it, you’re asking for trouble. Maybe not this session or the next, but eventually things will catch up to you.

A better strategy is to delay your gratification by training around the problem (finding an exercise or variation that doesn’t hurt, or avoiding that joint altogether) so your body can heal up quickly and you can resume your normal workouts in a timely manner. This way, you’ll be more successful down the road. Sure you can down that marshmallow by psyching yourself up and pulling that heavy deadlift PR even though your body hurts, but you might only get one marshmallow that way. If you chill out and train intelligently, you’ll likely get two marshmallows in due time.

Hindsight is 20/20

Many lifters have learned the hard way that they should have listened to their bodies. Don’t wait until it’s too late. Delay your gratification, nip the problem in the bud, and live to train pain-free another week. That’s the name of the game!

Good article! I’ve been suffering from knee and shoulder pain but kept going at it despite the pain. Then one day my knee felt like it was going to give whilst squatting. I have since decided to stop squatting for a while. I miss it and want to continue, was thinking of trying it tonite. Then I read your article. I think I’ll focus on other exercises. I’ve even promised to do hip thrusts at least twice a week. thanks for the info!

I agree with training around joints that hurt, but isn’t that part of the game? I stretch 3-4 times a week and foam roll once or twice a week, but I can honestly say their isn’t a day I am completely pain free. A lot of the time my joints ache or are a little painful until I am a few sets in. A good example would be my left knee. The outer part of my knee usually aches and doesn’t feel good when I begin to squat. The pain goes away after its nice and warmed up and it doesn’t hurt doing anything else. So, I simply put up with it. I feel that I know my body well enough to know when its a serious pain and I need to stop training. I just think pain is part of the game. I think each individual person needs to learn what is normal and what is bad. Or am I doing it wrong? lol

Interesting study about the marshmellows. Delayed gratification can be difficult because it requires patience and intelligent design. This mentality could be very important for me to achieve my goal, a 40 inch vertical leap. I peaked on my speed training at around 35 or so inches of vertical and decided I need to increase my limit strength. I noticed a slight decrease in my running vert, and increase in my standing since the change in focus. Its not as much fun to see my reactivelity decrease but I think once I can increase my force capacity, ill have more potential for power. Great article BC

As with any wisdom in life, it’s easier said than done. I guess I’m most likely the kid that ate the marshmallow after 30 seconds.

Lately I´ve been in a rut and it´s been quite hard to find time to hit my workouts.. I love doing so much but betweent the power 4, mobility and accesory.. when I do get to train I have to be very smart with the time I have to pick the right exercises and allow my body the sufficient time to rest and recover, which most of the times is a factor left out and that´s why people get the injuries you mention.

Hey, Bret, good article. Being able to step back and consider you -might- be doing something wrong or at least overdoing it is definitely a mark of (growing) maturity in a strength athlete or lifter. I myself recently decided to address why my knees ached after squats by using mini-bands to force me to push my knees out, among other corrections. Sometimes it’s really one’s ego that must be sacrificed in order to deload and improve form. But in the long run, I think the lifter will definitely be happy to do so.

I used to bench with elbows flared 245×4, but I knew/discovered it was wrong, and deloaded a few months ago. It felt crappy, but now I’m already back to 205×5, and at this rate should be 2-plating in no time. I’m 22, so I think it’s a good idea to take advantage of my youth and make sure I use good form so maybe when in 5-10 yrs….hopefully will be hitting really big numbers.